For centuries, Shakespeare’s plays have been at the heart of European culture. Owing to their canonical status in European drama and theatre, they have been used both to reflect on and to advance aesthetic, social and political transformations in Europe. Over time, they have served to develop theatrical and cultural patterns, to stimulate social, political and historical changes, to form the notion of nationhood in individual countries, and to shape a sense of common European identity.

Performances of Shakespeare’s plays on the Continent date back to his lifetime. Between the end of the 16th century and the reopening of theaters in England in 1660, English companies successfully toured vast and diverse geopolitical areas, including today’s Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, France, Denmark, Estonia, Poland, Czech Republic and Russia. The English actors staged the works of Shakespeare and his contemporaries at imperial and royal courts, fencing schools, town markets, inn-yards, churches and churchyards. They adapted the scripts and adjusted their performance style for audiences of widely ranging status, education, wealth, religion, ethnicity and language.

Initially, Shakespeare was performed on the Continent in English. In busy cosmopolitan cities like the 17th century Gdańsk, which boasted one of the first stationary public theatres in Central Europe and had the largest English-speaking community on the Continent, there were many spectators capable of appreciating the subtleties of stage dialogue. Those who did not understand English could enjoy physical action, juggling and clowning. Over time, English companies touring the Continent began to employ German or Dutch actors and perform in German to reach wider audiences. Translated into German, Shakespeare’s plays were heavily adapted, often in prose with elements of dialect. The first collection of plays staged by English companies, published in Germany in 1620 and reprinted in 1624, entitled Englishe Comedien und Tragedien, edited by Friedrich Menius, includes two plays which echo Shakespeare: The Most Lamentable Tragedy of Titus Andronicus and Julio and Hyppolita, which is reminiscent of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the title and of The Two Gentlemen of Verona in the plot development.

The first complete translations of Shakespeare’s plays were produced in French and German. Between 1776 and 1783 twenty volumes of collected plays appeared in Pierre Le Tourneur’s translation. From 1762 to 1766 Christoph Martin Wieland published a prose translation of twenty-two plays in German, which Johann Joachim Eschenburg emended and completed between 1775 and 1782. The complete translation began by August Wilhelm von Schlegel and finished by Ludwig Tieck in 1833 became the masterwork of German language, establishing Shakespeare as the third greatest German author, after Goethe and Schiller. Shakespeare’s remarkable reputation in the 18th century is further testified by the fact that his plays were translated by the enlightened rulers: Tsarina Catherine the Great adapted Merry Wives of Windsor into Russian as This Is What it Means to have a Buck-Basket and Linen and Timon of Athens (on the basis of a German translation) as The Spendthrift. The last Polish king Stanislaus August Poniatowski translated Julius Caesar into French, the language of his court.

An increased interest in translating and staging Shakespeare occurred at the end of the 18th century, coinciding with the development of Romanticism, the spread of national attitudes and the cultural revival in numerous countries across Europe. Initially Shakespeare’s works tended to be translated from German or French; they were frequently altered to suit neo-classical tastes still prevalent on the Continent. In Restoration England they were adapted (and often censored) in terms of their language, plot and themes to reflect aesthetic, cultural and political alterations. Rewritings such as John Dryden and William Davenant’s The Tempest or The Enchanted Island (1670), Nahum Tate’s The History of King Lear (1681) or Colley Cibber’s Richard III (1699) enjoyed such popular success that they replaced Shakespeare’s plays on the English stage until the middle of the 19th century. By the end of the 19th century, however, Shakespeare’s texts were being restored in England and available in the first-hand translations in most European countries. They have, thus, become key forces in the development of theatre and literature throughout the Continent. While his plays were used as aesthetic and political manifestos, Shakespeare was appropriated as a canonical writer in diverse regions and traditions in Europe.

By the end of the 18th century, Shakespeare was hailed as the national poet of England, with the actor manager David Garrick laying the foundation for the Romantic worship of the Bard and establishing Stratford-upon-Avon as the center of his commemoration. The Garrick Jubilee held in Stratford in 1769 constitutes a key point in the development of bardolatry, the Shakespeare industry and Stratford pilgrimage. During the 19th century, Shakespeare was announced as a genius playwright by the greatest Romantic poets in England and on the Continent, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, A W Schlegel, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, or Adam Mickiewicz. They praised Shakespeare for his masterful poetry and characterization, drawing on his works in their critical and creative writings.

The Tragedy of Hamlet became the favorite play of Romantic artists and audiences, who found in the portrayal of Hamlet a reflection of their personal and political anxieties. They interpreted the eponymous protagonist as a vulnerable intellectual, a heroic figure crushed by the corruption and evil of the world. Goethe’s description of Hamlet as a “lovely, pure, noble and most moral nature, without the strength of nerve which forms a hero,” who “sinks beneath a burden which it cannot bear and must not cast away” became the key to the interpretation of the protagonist and the whole tragedy for generations of readers, also outside Germany. In 1844 the German poet Ferdinand Freiligrath declared that “Deutschland ist Hamlet” and in 1905 the Polish playwright and painter Stanisław Wyspiański stated that “the puzzle of Hamlet is what is to be thought in Poland.”

The canonical status of Shakespeare along with a great availability of his plays on stage and in print resulted in the profusion of Shakespearean burlesques. While the greatest actor managers of the 19th century, such as John Philip Kemble, Charles Kean or Henry Irving staged grandiloquent productions of Shakespeare to show off their skills and educate the spectators, the producers of burlesques ridiculed and challenged not only specific performances, but the very idea of bardolatry. Popular both in Britain and on the Continent, burlesques relied on the extensive theatre culture of their audience, who learned about Shakespeare by watching performances rather than reading plays at school. While mocking the legitimate, high-brow Shakespeare, burlesques also confirmed the status of the playwright as a national and cultural icon, an idolized writer of the 19th century European theatre.

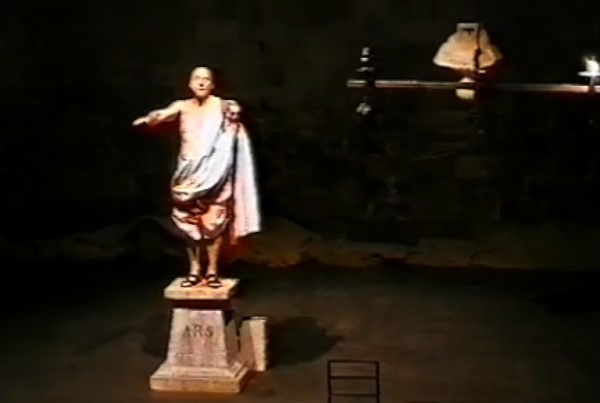

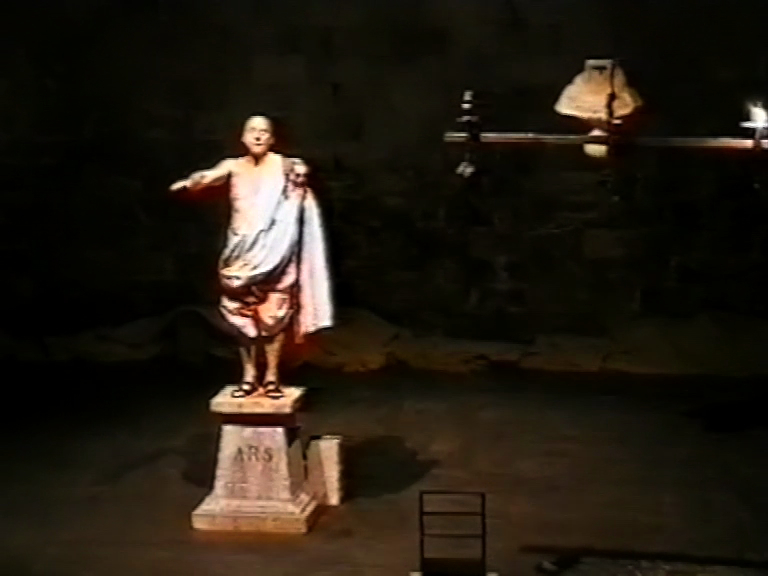

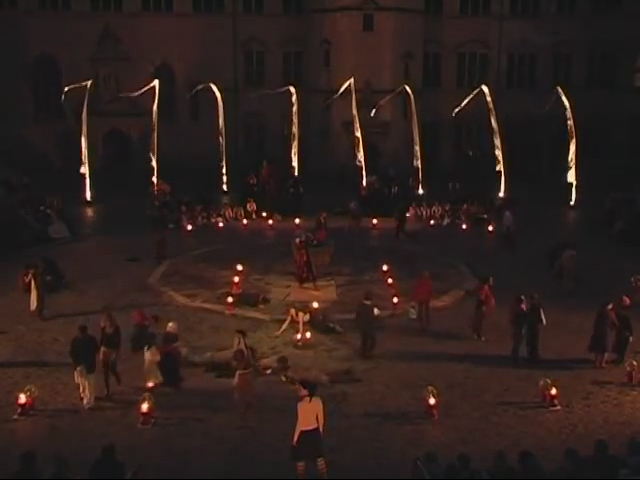

When cultural and historical values shifted, so did the position of Shakespeare on European stages. In the tumultuous period between the First and the Second World War, Shakespeare was performed in the context of social and political transformations, as new models of government and new political systems formed on the Continent. Julius Caesar became a topical play in several countries. In Italy, where Benito Mussolini fashioned himself as a modern Caesar and Julius Caesar was introduced by the Ministry of Education as an obligatory text in middle schools, the staging of the tragedy directed by Nando Tamberlani in Basilica of Maxentius in Rome in 1935 became a powerful example of fascist propaganda. This monumental and massively attended production was shown two months before the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Among other memorable performances of Julius Caesar of the period are those by Leon Schiller at the Polish Theatre in Warsaw in 1928, by Eduards Smiļģis at the Daile Theatre in Riga in 1934 and by Jiří Frejka at the Prague National Theatre in 1936. All these productions reflected both the political tensions and innovative performance tendencies in the interwar Europe.

After the horrors of World War II Shakespeare was identified as a healing force, a cultural icon, and a universal genius who transcended political conflicts and opened the possibility of a shared European identity. The establishment of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford in 1951 and the Shakespeare Bibliothek in Munich in 1964 as international centers of Shakespeare study was aimed at fostering collaboration above geographical and political distinctions. Soon, however, it became evident that rather than transcending politics, Shakespeare’s plays continue to be intimately involved in it. The end of the war did not mean the end of totalitarian regimes in Europe, and the works of Shakespeare were appropriated on both sides of the Iron Curtain to reflect upon the most pressing historical and political issues. In German-speaking countries they were often performed to confront the spectators with the post-Nazi guilt and the war trauma; the most striking examples include productions of The Merchant of Venice by Georg Tabori at Munich Kammerspiele in 1978 and by Hanan Snir at Weimar Theatre in 1995.

In Eastern Europe, Shakespeare was appropriated by the official propaganda as a class-conscious writer, but productions of his plays contained subversive messages, which undermined the communist system and defied the Soviet oppression. Jan Kott’s collection of essays, Shakespeare Our Contemporary (1961) became one of the most celebrated approaches to interpreting and performing Shakespeare in the context of the 20th century politics. Kott postulated the idea of the Grand Mechanism, which continuously creates and crushes the rulers. The production of Hamlet directed by Roman Zawistowski at the Old Theatre in Cracow in 1956, a few weeks after the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, was analyzed by Kott as a sharply political statement, an interpretation focused on spying and surveillance.

When communist regimes began to crumble and fall across Europe, Shakespeare was performed to reflect both postmodern influences on contemporary stage and the changes on the political and economic arena. Heiner Müller’s production Hamlet / Maschine, which combined his translation of Hamlet with his radical rewriting of the play as Hamletmaschine was staged in 1990 as a striking commentary on the political transition in Europe. A daring experiment in dramaturgy and staging, the production was also interpreted as a farewell to the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, symbolized by a melting block of ice, and a proclamation of a unified, democratic and capitalist Germany, represented by Fortinbras in a business suit. Zbigniew Herbert’s poem “Elegy of Fortinbras” published in 1961 (incidentally, the same year as Kott’s study), in which the Norwegian prince promises to introduce a new order in Denmark, was read in the background as an ironic observation on post-communist transformations in Europe.

Kott’s description of Shakespeare as a writer revealing the fundamental mechanisms of history and the basic instincts of human nature has greatly inspired generations of directors, including Peter Brook, whose deeply imaginative and symbolical A Midsummer Night’s Dream staged with the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford in 1970 became a landmark in the contemporary Shakespeare performance and the 20th century theatre. The production is an extraordinary example of Shakespeare’s plays participating in the most important changes in European staging, including the shift from a pictorial stage of the 19th century to non-realistic patterns of performance in the 20th century. Non-realistic productions of Shakespeare’s plays that became deeply influential in contemporary theatre include Oscar Koršunovas’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, produced in Vilnius in 1999, in which wooden boards were used as costumes, props and elements of the setting. Another groundbreaking example of European theatre and Shakespeare performance is Degustación de Titus Andrónicus of the Catalan company La Fura dels Baus, which premiered in San Sebastian in 2010 as a multimedia spectacle, involving dance, walking on stilts, live cooking and public consumption of food.

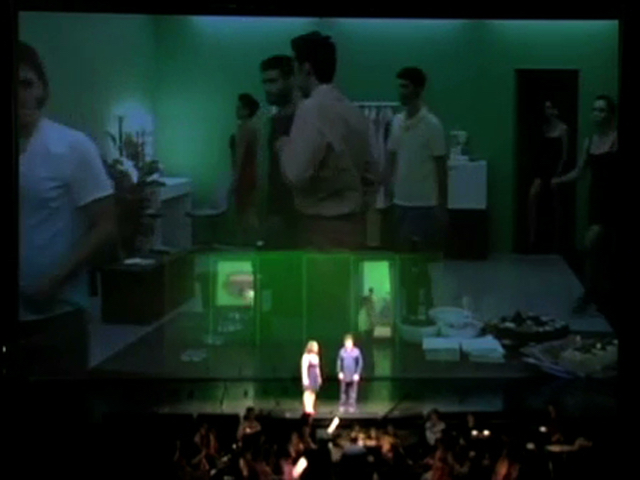

Performances of Shakespeare in the last decades have tended to continue the tradition of political interpretation along with an investment in stage innovation. Productions directed by Ariane Mnouchkine as “Les Shakespeare” Cycle at the Cartoucherie in Paris: Richard II in 1981, La Nuit des Rois (an adaptation of The Twelfth Night) in 1982 and Henry IV, Part I in 1984 were political and artistic manifestos of the director, who continues to be deeply inspired by Oriental theatre traditions of Indian kathakali and Japanese kabuki. Jan Klata’s H., a production of Hamlet staged in 2004 in the Gdańsk shipyard (the scene of the workers’ strikes in the 1970s and 1980s; now largely disused) confronted the audience with the consequences of democratic and capitalist reforms in Poland in an iconoclastic, site-specific performance. Ivo van Hove’s Roman Tragedies (a six-hour long adaptation of Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra), produced with Toneelgroep Amsterdam in 2007, translated ancient struggles for power into a multimedia setting and a television news format.

What is new in approaches to staging Shakespeare in Europe in recent decades, apart from a growing use of television, video and computers on stage, is an increased interest in non-English productions. For centuries English-speaking directors and actors dominated the Shakespearean tradition, providing a basic point of reference for spectators, reviewers and scholars around the globe. The last decades, however, have brought a growing appreciation of foreign productions of Shakespeare, with artists, audiences and academics travelling around the globe on an unprecedented scale to participate in international festivals and conferences. The Complete Works Festival, which took place in Stratford from April 2006 to March to 2007, showcased not only highly acclaimed English performances, but also productions from different parts of the globe. The World Shakespeare Festival, which takes place in London and other venues in Britain in 2012, features a wide range of theatre and performance from different countries, staged in different languages. Finally, the Global Shakespeares archive itself not only acknowledges but also promotes the awareness of cultural and linguistic richness of Shakespearean performance. We can no longer ignore the fact that Shakespeare’s plays are not exclusively English, since for four centuries they have been adapted and adopted into various cultures. As part of the world heritage they have become German, Italian, Romanian, Spanish, Polish etc., or, on a global scale, European, Asian, American, African, and more. It is through this intertwined network of sources and cultural influences that we may more fully comprehend both the interpretative potential of Shakespeare’s plays and the global character of our world.

Sources and Further Reading

Cinpoeş, Nicoleta. (2010). Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Romania, 1779-2008: A Study in Translation, Performance, and Cultural Adaptation. Lewiston, N. Y. : Edwin Mellen Press.

Delabastita, Dirk, and Lieven D’hulst, eds. (1993). European Shakespeares. Translating Shakespeare in the Romantic Age. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Dobson, Michael (1995). The Making of the national poet: Shakespeare, adaptation and authorship, 1660-1769. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gibińska, Marta, and Jerzy Limon, eds. (1998). Hamlet East-West. Gdańsk: Theatrum Gedanense Foundation.

Gregor, Keith. (2009). Shakespeare in the Spanish Theatre: 1772 to the Present. London; New York: Continuum.

Hattaway, Michael, Boika Sokolova, and Derek Roper, eds. (1994). Shakespeare in the New Europe, a collection of conference papers. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Hortmann, Wilhelm. (2009). Shakespeare on the German Stage: Volume 2, The Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, Dennis, ed. (1993). Foreign Shakespeare: Contemporary Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kujawińska-Courtney, Krystyna. (2010). “Shakespeare in Poland: Selected Issues.” Internet Shakespeare Editions, University of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Criticism/shakespearein/poland1.html

Limon, Jerzy. (1985) Gentlemen of a Company: English Players in Central and Eastern Europe 1590-1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schandl, Veronika. (2008). Socialist Shakespeare productions in Kádár-Regime Hungary: Shakespeare behind the Iron Curtain. Lewiston, N.Y. : Edwin Mellen Press.

Schoch, Richard W. (2002). Not Shakespeare. Bardolatry and Burlesque in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

“Shakespeare Translations in Europe (general overview).” (2007). Shakespeare in Europe. University of Basel, Switzerland. http://pages.unibas.ch/shine/translators.htm

Shurbanov, Alexander, and Boika Sokolova. (2001). Painting Shakespeare Red: An East-European Appropriation. London: Associated University Presses.

Stříbrný Zdeněk. (2000). Shakespeare and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Simon. (1990). Shakespeare on the German Stage: Volume 1, 1586-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, Stanley. (2002). Shakespeare for All Time. London: Macmillan.