Co-authored by Anna Stegh Camati, Cristiane Busato Smith, and Liana Leão

Shakespeare’s incursion into Brazil goes back to the early nineteenth century, when French mediation of the playwright’s texts was initiated by European companies. Later on, during the mid-nineteenth century, João Caetano (1808-1863), considered the father of Brazilian theatre, started to perform Shakespeare on local stages. All his productions, except for his 1835 Hamlet based on an English original, relied mainly on Brazilian Portuguese translations of French neoclassical adaptations by Alfred de Vigny, Jean-François Ducis and others. Caetano’s greatest Shakespearean role was Othello which he would perform twenty-six times between 1837 and 1860. Though audiences applauded the French adaptations, in 1871, prominent novelist Machado de Assis (1839-1908) obliquely criticized them, albeit praising Caetano’s interpretations comparable to those of great international stars visiting the country in the late nineteenth century. Like Machado, who created a Brazilian Otelo in his novel Dom Casmurro (1899), many other Brazilian writers and intellectuals, such as Gonçalves Dias, Álvares de Azevedo, Joaquim Nabuco and Martins Pena made reference to Shakespeare’s plays in most of their literary productions.

After João Caetano’s death in 1863, Shakespearean productions, performed with local casts, reappeared on Brazilian stages only in the 1930s. After living many years in England, upon his return to Brazil, diplomat Paschoal Carlos Magno (1906-1980) decided it was high time to discard the French influence. With the Teatro do Estudante do Brasil (TEB), an amateur group formed by students, Magno produced, in the forties, a very successful Romeo and Juliet, followed by As You Like It, and culminating with a much celebrated Hamlet. Directed by Wolfgang Hoffmann Harnisch, this 1948 Hamlet launched the careers of many Brazilian actors such as Sérgio Cardoso (1925-1972), who played the title role, Maria Fernanda (1928-) and Sérgio Britto (1923-2010). Cardoso’s Hamlet became a landmark in the history of theatrical performances in Brazil: since then the quality of Shakespeare on Brazilian stages changed forever.

After the revival of interest in Shakespeare, promoted by Paschoal Carlos Magno and the TEB, other professional Brazilian theatrical companies started mounting his plays. When in 1967, Barbara Heliodora, Brazil’s leading authority on Shakespeare wrote that Shakespeare’s story in Brazil was “short and sad”[1], she was referring to the scarcity of translations and the lack of “stageworthy quality” in productions of the English bard. This sad story is no longer true: from the 1980s onwards, Shakespearean productions have appeared in Brazil with increasing frequency. No longer European-mediated, the plays are now inflected with a distinct Brazilian accent, both in terms of their reception and transmission. Printed translations are now plentiful and offer different versions of the canon in Brazilian Portuguese: while some are of a more scholarly nature, in ornate prose and verse, others resort to colloquial prose; some are page-oriented, while others bring out the plays’ performability on stage[2].

Shakespeare reflects the norms and stereotypes of the culture in which he is performed, hence his presence in Brazil has shifted meanings to represent him according to different logic, ideology and concerns. Whereas Shakespeare’s European-mediated presence in 19th century reflects Brazil’s colonial dependence, the twentieth century maps the political, social and artistic transformations brought by different governments and innovative aesthetic practices in contemporary Brazil.

During the military regime (1964-1985), Shakespeare became a vehicle to both legitimize the government and denounce the repressive power of the state. While the military government supported the festivities that celebrated Shakespeare’s 400th birthday as a means to divert people’s attention from the political unrest, productions such as Julius Caesar (1966) and Richard III (1975), directed by Antunes Filho, and Celso Nunes’ Coriolanus (1973), although meant to voice the angst of the time, in fact failed to achieve such critical intent. Hence, the first angry cry against political oppression in Brazil was A tempestade (1979), a radical recreation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest by Augusto Boal, theatre practitioner and founder of Theater of the Oppressed, who “nationalized” Shakespeare by underlining a relationship of independence rather than dependence from the original text, a paradox that remains central to contemporary renegotiations of Shakespeare in Brazil.

The political dimension of Shakespeare’s texts found deeper resonance after the civilian government was restored in 1985. Since then, Shakespeare’s tragedies, mainly Hamlet and Macbeth, have been continually appropriated to contest hegemonic discourses, reinterpret cultural and identity issues, expose urban violence and denounce political corruption. Productions mounted in 1992, such as Marcelo Marchioro’s Hamlet, Ulysses Cruz’s Macbeth and Antunes Filho’s Trono de sangue [Throne of Blood] emerged out of the ferment of popular riots in the streets against Fernando Collor de Mello, the first President elected directly by the people after the dictatorship period, who resigned during the impeachment proceedings against him. Many political productions followed, among them Enrique Diaz’s Ensaio. Hamlet (Rehearsal. Hamlet) for the Cia. of Atores (Company of Actors) in 2004, which explored current problems surfacing after the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the first President of the Workers’ Party (PT) in Brazil. In 2006, two Shakespearean productions of Richard III protested against the turmoil and scandals that were current near the end of the first term (2003-2006) of President Lula’s administration: Ricardo III, directed by Jô Soares, and Ricardo III, directed by Roberto Lage.

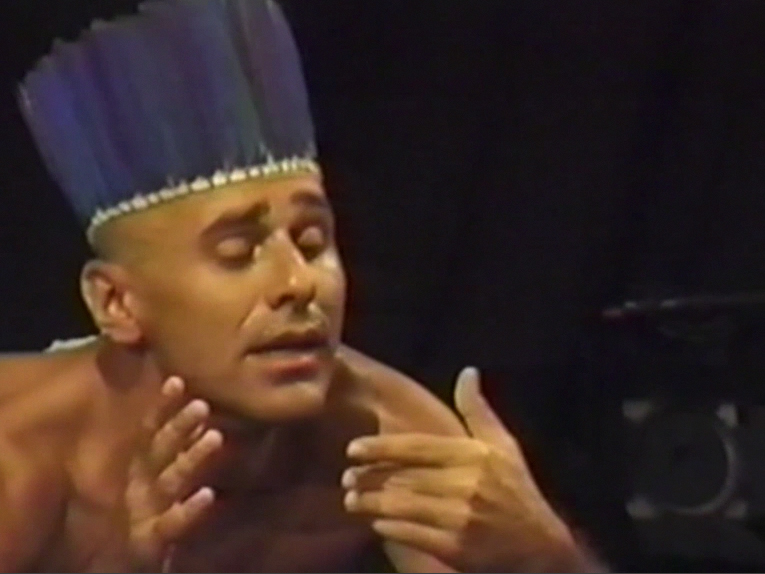

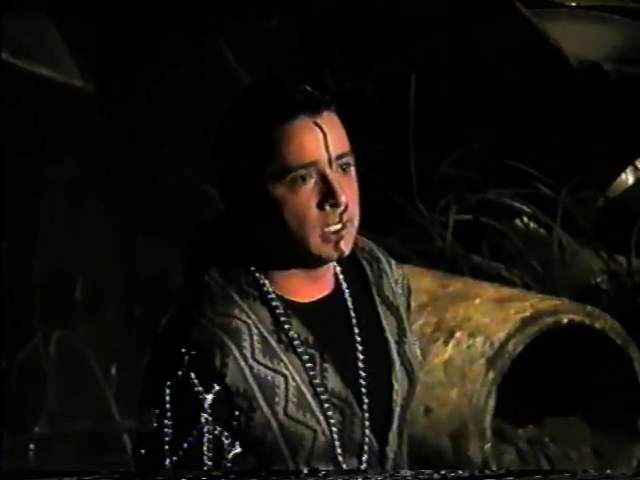

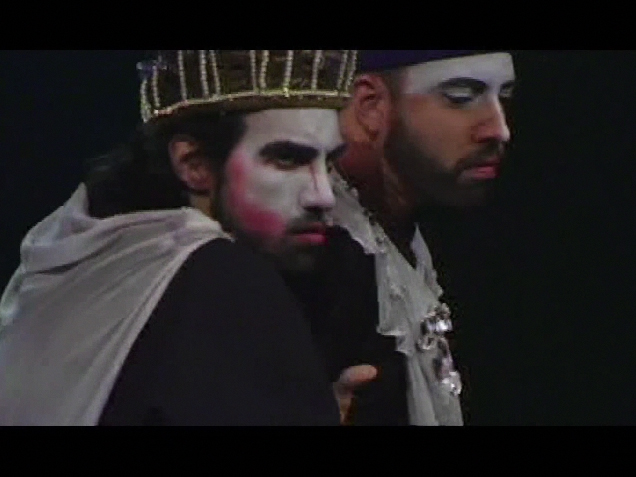

Another significant production of the post-dictatorship period is Ham-let (1993/2001), directed by one of Brazil’s most celebrated and experimental theatre practitioners, José Celso Martinez Corrêa. This exuberant rendition of Hamlet, lasting more than five hours, resignifies Shakespeare through the tenets of Oswald de Andrade’s cannibalist manifesto, heralded by the refrain “tupy or not tupy”, which opens the play and reverberates throughout the show. Indeed, cultural anthropophagy remains a fundamental concept to understand Brazilian aesthetic practices – it is anchored on the idea that Brazil’s strength lies in its talent to appropriate and assimilate (rather than reject) other cultures as it forges its own cultural identity.

During the 1980s, two politicized TV Globo miniseries – Romeu e Julieta (1980) adapted by Walter George Durst, and Otelo de Oliveira (1983) by Aguinaldo Silva – brought Shakespeare closer to the masses, introducing Brazilian social realities and problems into the plays, such as poverty, violence, and issues of class, race and gender. Shakespeare’s popularity increased in the 1990s when, besides politically engaged renderings, a wide range of other tendencies emerged, among them street theatre, musicals and intercultural readings. Theatre groups from different Brazilian regions started to adapt Shakespeare’s plays for popular audiences, performing them in the streets, squares, parks, marketplaces and other venues of great public circulation. Grupo Galpão’s Romeu e Julieta (1992) – twice successfully presented at London’s Globe Theatre in 2000 and 2012 –, Clowns de Shakespeare’s Sua Incelença, Ricardo III (2010), and Grupo Ueba’s A megera domada (2009), to mention only a few, are important open-air renderings.

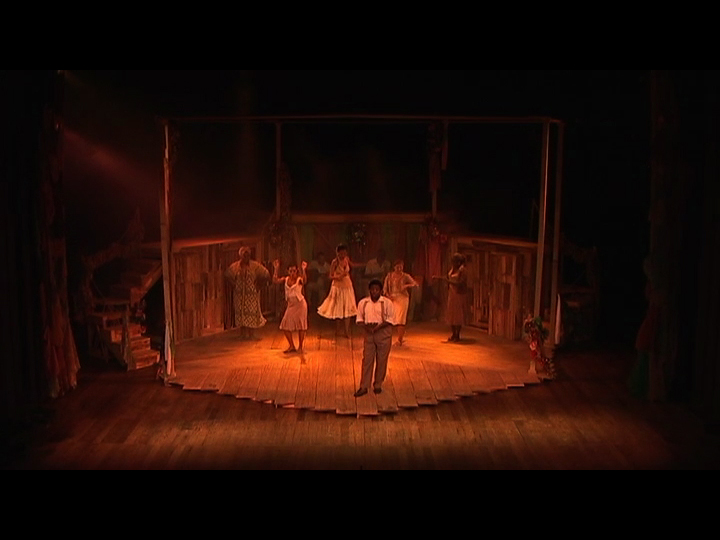

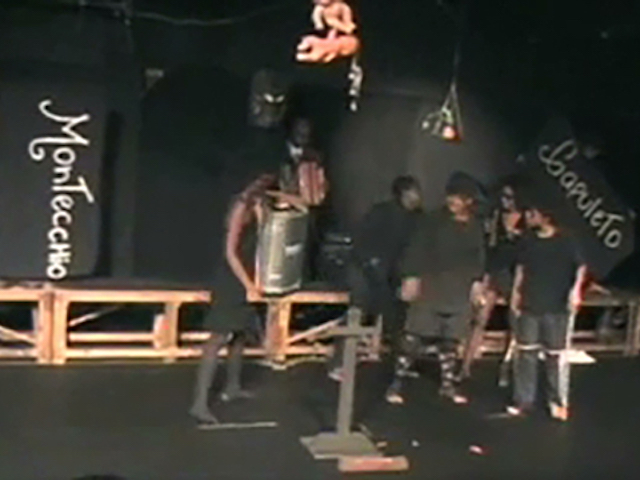

Intercultural readings have been privileged by Brazilian indoors theatre ensembles as well, such as Nós do Morro (We from the Hillside), a community based theatre group at the Vidigal favela (shantytown) in Rio de Janeiro, directed by Guti Fraga, and Caixa-Preta (Black-Box), a group of black actors, based in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, directed by Jessé Oliveira. In their 2004 Sonho de uma noite de verão: uma intromissão do Nós do Morro no mundo de Shakespeare (A Midsummer Night’s Dream: an intrusion by Nós do Morro in the Shakespearean universe), the troupe explored the possibilities of the universe of the favela, while Caixa-Preta highlighted Afro-Brazilian traditions and mythologies in their 2005 Hamlet sincrético (Syncretic Hamlet). Nós do Morro’s Os dois cavalheiros de Verona (The Two Gentlemen of Verona) was commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company for their 2006 festival.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, Brazilian musical adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays, combining theatre, music and dance, have also surfaced in Brazil. Otelo da Mangueira (2006), directed by Daniel Herz, transposed Othello to the vibrant world of the Mangueira Samba School in Rio de Janeiro in the 1940s, imprinting the local color of the favela (shantytown) onto the Shakespearean universe. Patricia Fagundes’ Sonho de uma noite de verão (2006), a musical version of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is set in a twentieth century cabaret or nightclub instead of the sixteenth century forest of Arden.

To celebrate Shakespeare’s 450th jubilee of birth and his 400th death anniversary, a great number of plays have recently been mounted by Brazilian theatre practitioners, among them Ricardo III (2014), directed by Sérgio Módena, in which actor Gustavo Gasparani gives life to 26 characters, including a narrator to situate the action of Richard III; Timon de Atenas (2014), directed by Bruce Gomlevsky, with actress Vera Holz incarnating Timon; A tempestade (2015), an intercultural reading of The Tempest by Gabriel Villela; Domando a megera (2015), a musical inspired in The Taming of the Shrew produced by Nós do Morro; Macbeth and Medida por medida [Measure for Measure], both directed by Ron Daniels in 2015-2016; Hamlet, um processo de revelação [Hamlet, a process of revelation], a one-man show presented in 2016, in which the actor Emanuel de Aragão adopts the line of presentational acting, stepping in and out of the title role, and using a series of performance art resources; Troilo e Créssida (2016), translated and directed by Jô Soares; Coriolano (2017), directed by Márcio Boaro for the Ocamorana Theatre Company; and Hamlet (2017), produced by the Armazém Cia. de Teatro to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the company, directed by Paulo de Moraes, with Patrícia Selonk impersonating the prince. While some contemporary Brazilian renderings continue to overtly denounce political issues, others favor a more humanist approach to the plays. This is the case of a 2015 production of King Lear, which opts to focus on Lear’s lonely trajectory as an ordinary aging man rather than his political predicaments as a king. On a solo performance, celebrated actor Juca de Oliveira plays all the parts, but except for Lear, the lines of the other characters are drastically reduced.

Indeed, the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first centuries have ushered in a complete transformation of the scene: Shakespeare is now performed without European mediation, using Brazilian Portuguese translations of the originals and performed by Brazilian actors. The voices of the samba schools, of the circus, of street theater, the harsh reality of the favelas, the vibrant berimbaus and capoeira dance are among the many riches that bring new accents to the plays. Shakespeare has found “a local habitation” in Brazil: besides the multiple stage productions originating in different Brazilian regions in the last three decades, new translations, film adaptations, graphic novels and other manifestations of popular and mass culture have turned up, following the contemporary trend of popularization of the playwright’s work.

[1] See Barbara Heliodora’s article “Shakespeare in Brazil” (Shakespeare Survey, ed. Kenneth Muir, v. 20, Cambridge University Press, 1967, p. 121-124).

[2] See <http://www.dbd.puc-rio.br/shakespeare>, a website featuring a database of Brazilian Portuguese translations of Shakespeare’s plays in book form, compiled and organized by Marcia do Amaral Martins.