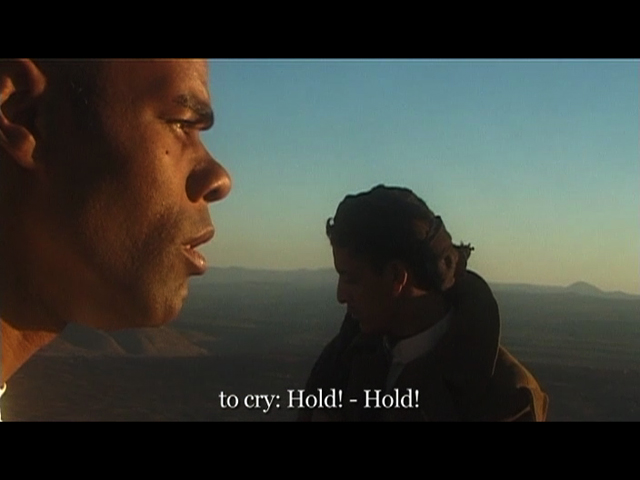

Shakespeare adaptations have been a staple of the modern Arab theatre since the late 19th century. They respond to a global kaleidoscope of international sources and models: not only British texts but also French plays, Italian operas, German novels and literary criticism, Soviet films, and American productions and adaptations. Most Shakespeare-based works are in standard Arabic, the formal language used by intellectuals for literary and media writing throughout the Arab world. But some Shakespeare adaptations are in colloquial Arabic, and a few, such as the Moroccan Nabyl Lahlou’s Ophelie N’est Pas Morte (1969) and the Anglo-Kuwaiti Sulayman Al-Bassam’s The Al Hamlet Summit (2002), were originally written in French or English. Thus it is more accurate to refer to “Arab” rather than “Arabic” Shakespeares.

The first Arab encounter with Shakespeare was through the Egyptian stage, where Syrian-Lebanese immigrants, many knowing little English, retooled French translations of the plays to please Cairo’s emerging middle class. The point was not to produce literature for reading but to fill theatres. Najib al-Haddad (1867-99) adapted Romeo and Juliet around 1892 as a melodrama, The Martyrs of Love (Shuhada al-gharam). Tanyus ʻAbdu’s (1869-1926) French-based adaptation of Hamlet (1901, published 1902) was based on the French adaptation by Alexandre Dumas père [read English translation], and like its source it ended happily: Hamlet killed Claudius, accepted the Ghost’s blessing, and took the throne. Both The Martyrs of Love and Hamlet were musicals starring Quran-reciter-turned-popular-singer Shaykh Salama Hijazi (1852-1917), with the soliloquies replaced by singable arias. The first known Othello adaptation, thought to be by ʻAbdu as well, was titled Khayal al-rijal (The Wiles of Men, performed 1898, published 1910).

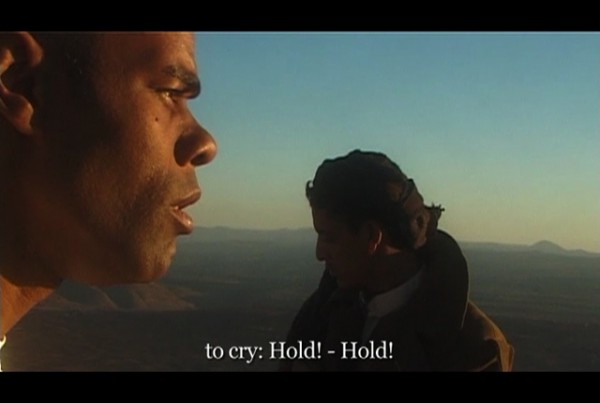

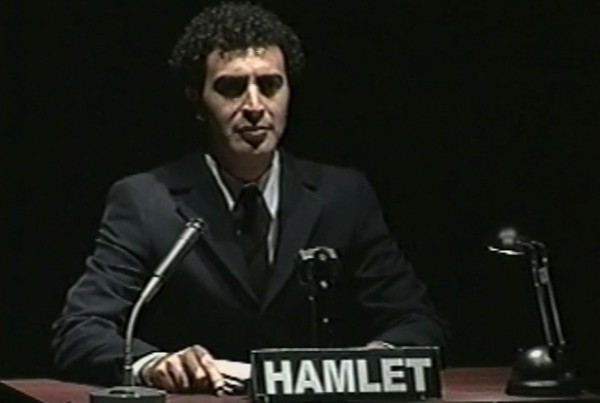

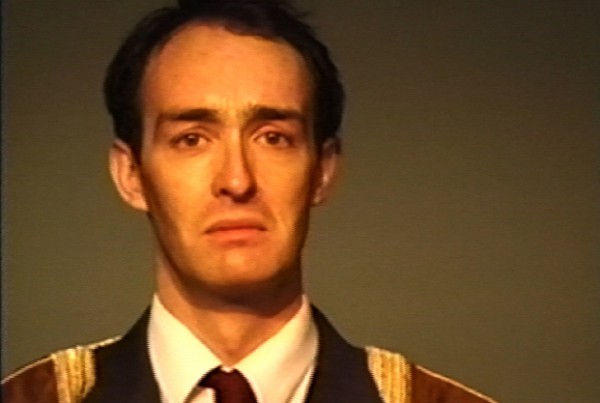

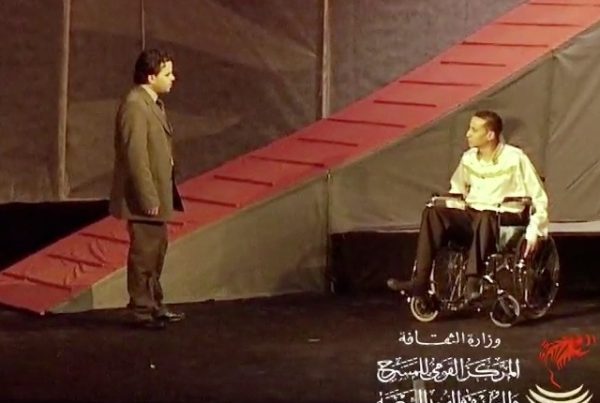

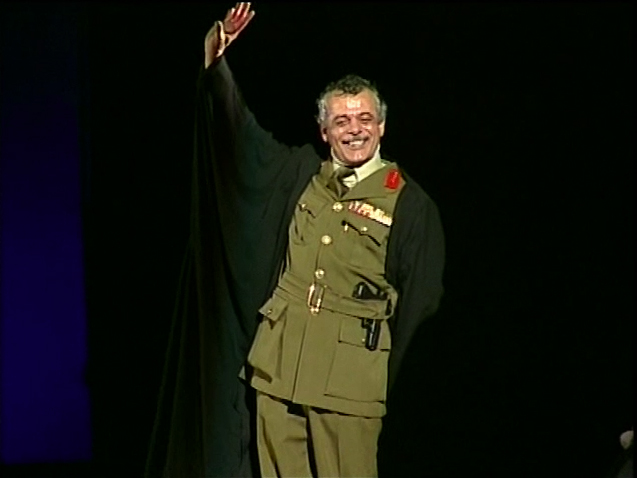

In the century since then, a vast variety of directors and adapters in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, and other Arab countries have produced versions of Shakespeare’s plays to speak to their own and audiences and circumstances. Othello has been adapted as a prooftext about Orientalism or a tragedy about gender violence. Hamlet has been played as a Che Guevara in doublet-and-hose, his “To be or not to be” interpreted as a cry for justice in what many theatre-makers see as rotten states and out-of-joint times [see lecture on this]. Julius Caesar, while rarely produced, has recurred frequently in political discussions about despotism and democracy. The Merchant of Venice has not escaped polemical appropriation by various sides of the debate about Zionism’s role in the Middle East. Romeo and Juliet has been staged as a demonstration of the dangers of blood feuds and arranged marriages. Taking a different approach, a 1994 Romeo and Juliet production in East Jerusalem (co-directed by the Israeli Eran Baniel and the Palestinian Fouad Awad) had the Capulets played by Israeli Jewish actors speaking Hebrew and their rivals the Montagues played by Palestinian actors speaking Arabic.