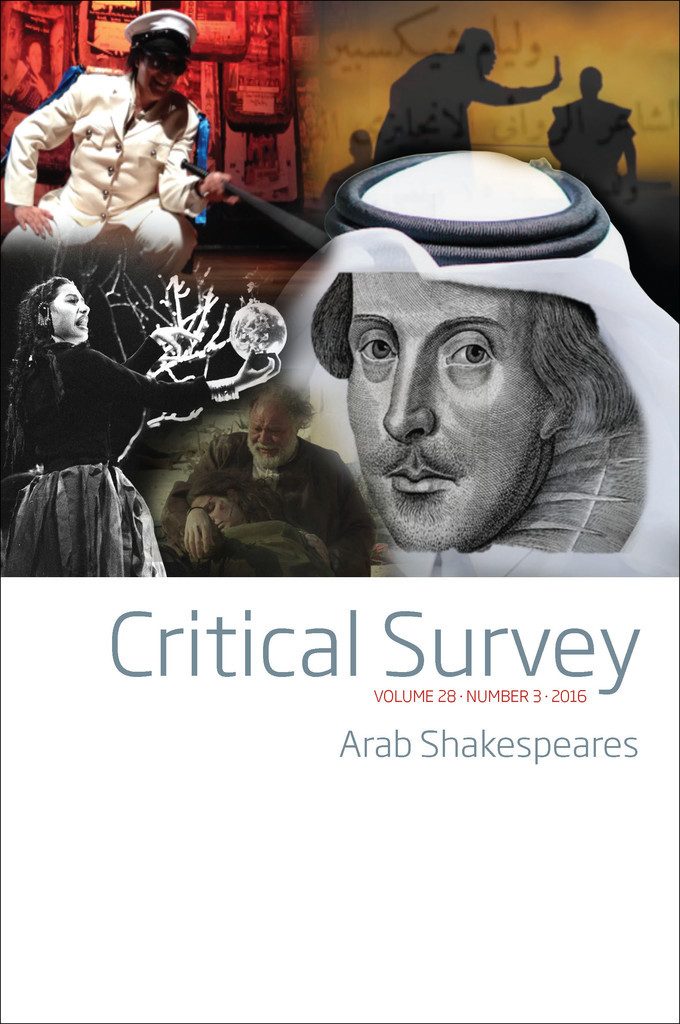

A newly published special issue of the journal Critical Survey (29:3) includes eight articles, six book or performance reviews, and a playwright interview – a total of 212 pages on Arab versions and appropriations of Shakespeare. The following excerpt is drawn from the introduction by guest editors Katherine Hennessey and Margaret Litvin.

When the first Critical Survey special issue on Arab Shakespeares (CS 19:3, Winter 2007) came out nearly a decade ago, the topic was a curiosity. There existed no up-to-date monograph in English on Arab theatre, let alone on Arab Shakespeare. Few Arabic plays had been translated into English. Few British or American theatregoers had seen a play in Arabic. In the then tiny but fast-growing field of international Shakespeare appropriation studies (now ‘Global Shakespeare’) there was a great post-9/11 hunger to know more about the Arab world but also a lingering prejudice that Arab interpretations of Shakespeare would necessarily be derivative or crude, purely local in value.

When the first Critical Survey special issue on Arab Shakespeares (CS 19:3, Winter 2007) came out nearly a decade ago, the topic was a curiosity. There existed no up-to-date monograph in English on Arab theatre, let alone on Arab Shakespeare. Few Arabic plays had been translated into English. Few British or American theatregoers had seen a play in Arabic. In the then tiny but fast-growing field of international Shakespeare appropriation studies (now ‘Global Shakespeare’) there was a great post-9/11 hunger to know more about the Arab world but also a lingering prejudice that Arab interpretations of Shakespeare would necessarily be derivative or crude, purely local in value.

A great deal – perhaps even the prejudice? – has changed. In Anglophone academia, the curators of any Shakespeare festival, edited volume, or university course with ‘global’ aspirations work hard to secure a contribution from an Arab perspective. They can now draw on several monographs, as well as the articles in that first CS special issue and many more in other publications, including several top journals of Shakespeare, theatre, and literature. In 2007 Sulayman Al-Bassam’s adaptation of Richard III became the first Arabic play commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company. By 2012, thanks largely to the RSC’s then-associate director Deborah Shaw, several Arab productions were commissioned as part of the World Shakespeare Festival timed to that summer’s Olympic Games in London. Arab institutions have also re-entered the arena. At the worldwide festivities marking the quadricentennial of Shakespeare’s death this year, for instance, one of the most ambitious events was organized by the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria, Egypt.

In these years the region itself has been an inexhaustible source of drama and, alas, tragedy. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011, consumed as spectacle, brought the cable network CNN the highest viewer ratings in its history. As the Grand Mechanism swung around once more, recent struggles in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen (and their repercussions in Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria) have presented dramatic instances of eloquence, pathos, heroism, and carnage. Syria’s civil war and the resulting wave of Arab refugees into surrounding countries and Europe has lent a sudden, urgent power to once dusty or over-the-top violent classic texts from Homer and Greek tragedy to Shakespeare.

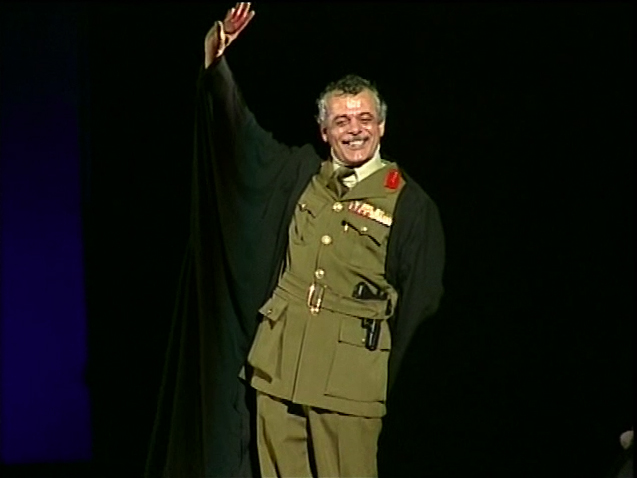

Richard III: An Arab Tragedy (2007),

dir. Sulayman Al-Bassam.

Arab theatre artists seeking to metabolize recent Arab-world events in or for the West have turned persistently to Shakespeare in particular – both from personal interest and in quest of a vocabulary their audiences (and sponsors) can understand. As state support for theatre has crumbled in many Arab countries, Shakespeare provides what Al-Bassam has called a ‘playable surface’: a slippery but usable platform on which an internationally mobile Arab artist can continue to produce work.[1] In response, artists have adapted both their texts and themselves. (Many Arab critics and scholars, fleeing abroad for safety or better working conditions, have done the same.) Topical new Shakespeare adaptations have probed the US occupation of Iraq (Al-Bassam’s Richard III: An Arab Tragedy, 2007); the wellsprings of political repression and revolt (his The Speaker’s Progress, 2011-12); Sunni-Shi‘a sectarian strife in Iraq and the rise of extremist Sunni movements (Monadhil Daood’s Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad, 2012); and the threat of recurring tyranny in post-uprising Tunisia (Anissa Daoud and Lofti Achour’s Macbeth – Leila and Ben: A Bloody History, 2012). Still more recently, Nawar Bulbul’s two projects in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp have cast Syrian children in versions of King Lear/Hamlet (2014) and Romeo and Juliet (2015), transfixing international journalists and others desperate for signs of hope.

The Speaker’s Progress (2011-12),

dir. Sulayman Al-Bassam.

But what about ‘local’ writers and directors, those who neither travel nor find international donors and audiences? Some Arab Shakespeare adaptations, such as the Upper Egypt-themed Lear TV series analyzed in this issue, do target a relatively homogenous audience within one country. Yet as the contributions in this issue make clear, one cannot draw a clear line between ‘global’ and ‘local’ Arab Shakespeares. From the very early twentieth century, translations into Arabic, whether literary- modernist or popularizing-vernacular, have been commissioned with one eye on Europe. Directors have reworked ideas picked up at international festivals or from Arab and international traveling companies. Moreover, some productions have regional rather than local or global significance. Whether pursuing audiences at ‘home’ or abroad, whether seeking to civilize the audience or float to fame on its expectations, any Arab artist who works with Shakespeare does so with a purpose. That has always been true but is perhaps most evident today. In the 21st century artistic climate of state withdrawal from the arts, festivalization, unpredictable funding, distracted audiences, self- and official censorship, and rising social stigma around the artistic professions in some Arab countries (not to mention the major security concerns that have made it hard to keep theatres open at all) – in this climate any decision to work with a canonical world source such as Shakespeare is taken strategically, for a reason; such work rewards analysis.

The Tale of ‘Aidarus Bin Mohammed al-Kindi (2013),

A Yemeni adaptation of The Merchant of Venice

from Aismur Ma’ish al-Siraj (The Lamp Will Keep You Company),

dir. Amin Hazaber.

This special issue offers a variety of perspectives on the history and role of Arab Shakespeare translation, production, adaptation, and criticism. With two essays and an interview focused on the twentieth century, we have avoided an exclusive and ahistorical focus on the present. We have also striven to strike a balance between internationally and locally focused Arab/ic Shakespeare appropriations, and between Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. In addition to Egyptian and Palestinian theatre, our contributors examine everything from an Omani performance in Qatar and an Upper Egyptian television series to the origin of the sonnets and an English-language novel about the Lebanese civil war. They address materials produced in several languages: literary Arabic (fuṣḥā), Egyptian colloquial Arabic (‘ammiyya), Moroccan colloquial Arabic (darija), Swedish, French, and English. They include veteran scholars, directors, and translators as well as emerging scholars from diverse disciplinary and geographic locations, a testament to the vibrancy of this field.

Naturally, there are many angles and manifestations of Arab/ic Shakespeare this collection leaves unaddressed, many avenues for future work; we have aimed for comprehension, not comprehensiveness. But in sum, it is a rich harvest. We thank Graham Holderness for inviting us to edit this special issue. We are grateful to our contributors for their diligence and to our peer reviewers for their insight. We believe that, taken together, the diverse fruits of their efforts constitute not only a set of new data points about how Arabs do Shakespeare but also a significant analytical contribution to the study of Shakespeare in translation and performance.

[1] Margaret Litvin, ‘For the Record: Interview with Sulayman Al-Bassam,’ in Alexa Huang and Elizabeth Rivlin, eds., Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation, (New York: Palgrave, 2014): 221-240.