Throwing a good party takes an inordinate amount of work, and Shakespeare commemorations are no different. I’m sure many of the organizers of the myriad events honoring Shakespeare’s death (and more optimistically, 400 years of afterlife) at some point during 2016 thought, “Why did I get myself into this?” Some of their other guests may too have shared a sense of the irony—dare we say overkill?—in making a bigger deal of the death than the 450th birthdate two years prior. (Granted, I was biased by being SAA President in 2014 and I do understand the appeal of round numbers, of centuries over half-centuries, in anniversaries as in cricket.) Taking it all in stride, our good hosts drew us along, pilgrims to the shrines, and now, after the party’s over, deserve our thanks and a rest. But as the dust and bones resettle, and even amidst more urgent contemporary upheavals, it seems a good time for reflection upon the gatherings of 2016 and their meanings for Global Shakespeares in particular. In a series of event-focused blogs, I start the ball rolling.

This journey begins on the date itself, 23 April 2016, at ground zero for fictional Shakespearean deaths: Elsinore. That weekend I attended a conference in Denmark conceived and coordinated by Ronan Paterson of Teeside University, UK, along with his organizing committee compatriots Dr. Yilin Chen, Dr. Ema Vyroubalova, Professor Ryuta Minami and Dr. Yukari Yoshihara, from universities in Taiwan, Eire, and Japan respectively; this very fact testifies to the happy distance academia has travelled in recognizing international “ownership” of Shakespeare.

This journey begins on the date itself, 23 April 2016, at ground zero for fictional Shakespearean deaths: Elsinore. That weekend I attended a conference in Denmark conceived and coordinated by Ronan Paterson of Teeside University, UK, along with his organizing committee compatriots Dr. Yilin Chen, Dr. Ema Vyroubalova, Professor Ryuta Minami and Dr. Yukari Yoshihara, from universities in Taiwan, Eire, and Japan respectively; this very fact testifies to the happy distance academia has travelled in recognizing international “ownership” of Shakespeare.

Ronan had enthusiastically circulated the idea at the European Shakespeare Research Association (ESRA) conference in Worcester, UK during the summer of 2015, and somehow it came into being with an energy matching the (perhaps irrational) exuberance of its title: “Shakespeare—the next 400 years.” Albeit with a skull dwarfing the castle as its graphic mascot.

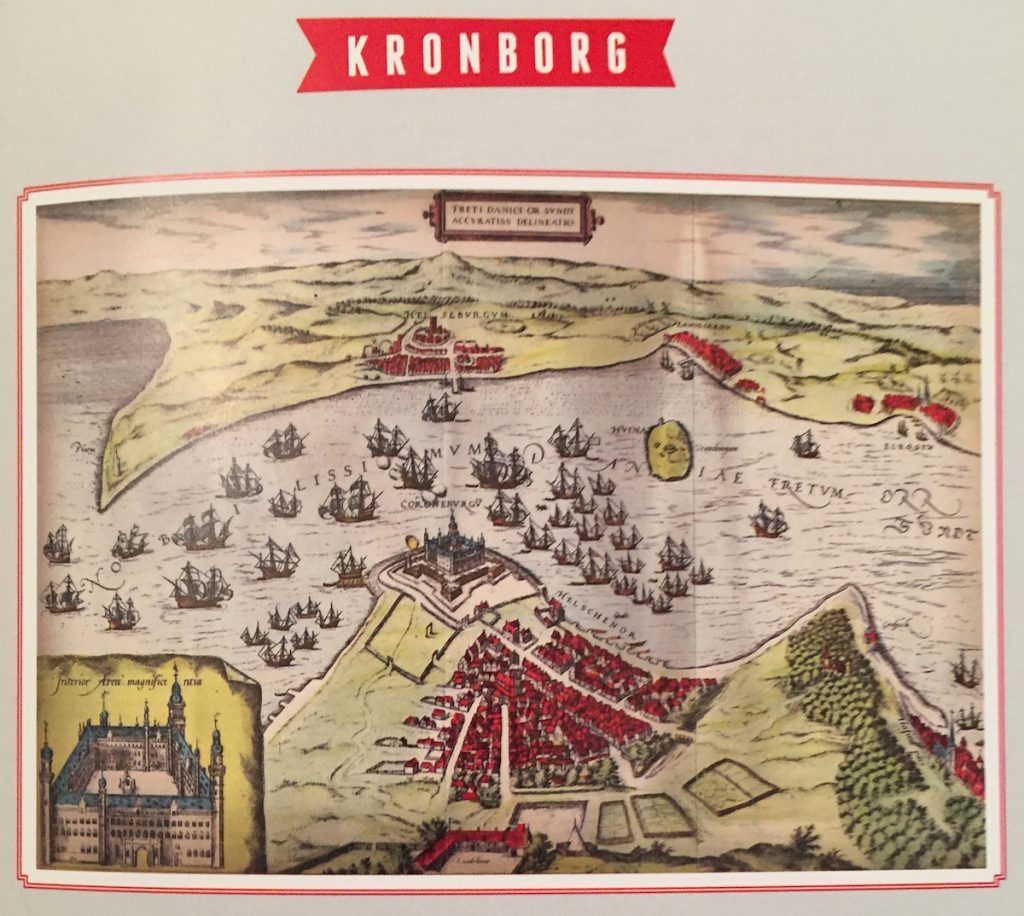

Of course, we were not actually at the fictive “Elsinore,” but we were meeting in—that is, quite literally, inside—the building which Shakespeare reconstructed as his setting for Hamlet: Kronborg Castle in Helsingør, Denmark. I had toured the castle years before on a summer daytrip up the Danish Riviera from Copenhagen, seeing the statue of the mythic figure Holger Danske in the dungeon and imagining the English players performing before King Christian IV in the elegant Renaissance hall (rebuilt after the disastrous fire of 1629). Being there had suddenly made real the castle’s strategic position in building Denmark’s royal coffers through enforced “protection” from pirates, as shipping passed through those narrow straits to the Baltic Sea: it thus also made the vision of North Sea pirates appearing as a mini-deus ex machina in Hamlet’s fourth act more plausible, far from the delightful farce of Sir Tom Stoppard’s recreation in Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead.

Now arriving at a chillier time of year and after the conference had begun, I had no opportunity to pause on the battlements and stare at Sweden across the 4 kilometers of water. Instead, I rushed straight to the south side of the castle courtyard and up the stony stairway into the halls where we were meeting—above the ground-level exhibits and below (quite directly) the wooden-floored halls where groups of heavily shod tourists were being shepherded. This time it was the idea rather than the historical particulars of the place that registered, as the excitement of the conference lay instead in its bold mixture of theory, archival work, pedagogy, and live performance by a truly global array of participants. After 30+ years of frustration caused by the “versus” many academics insert between text and performance, it was a pleasure to see the thorough interpenetration of these emphases at “Elsinore,” in the company of student and professional actors from Asia, Europe, and the Americas. But more than that, it indicated one of the enabling changes now allowing the concept of Global Shakespeares to flourish—and provided a link with the subsequent events of 2016 as well.

Among the memorable plenary speakers were Professor Judith Buchanan from York, UK, addressing “‘The future in the instant’: Shakespeare’s Janus gaze and ours,” and displaced Iranian (now Iranian-American) director and professor Mahmood Karimi-Hakak on “Shakespeare: The Initiator of Intimacy.” Professor Buchanan’s lecture moved from the First Folio’s prefatory paradoxes—making “true original copies” available, cured though maimed, as well as Jonson’s look/don’t look verses about the image of the “soul of the age” that was “not of an age”—to explore performance examples of comparably unsettling “temporality out of order” (a witty borrowing from the misprision of a malfunctioning ATM’s announcement). A co-curator of the British Library’s “Shakespeare in Ten Acts” exhibition, she discussed the Forbes-Robertson Hamlet that was among the treasures displayed there and its own myth of actorly succession and possibly apocryphal signatures. Buchanan then drew upon her deep knowledge of silent film to discuss the uncanny resemblances between the 1908 Vitagraph Julius Caesar’s assassination tableaux and Gérôme’s 1867 oil painting of “The Death of Caesar” before advancing to a contemporary Macbeth she is co-scripting: it similarly reaches back to a reel of a 1909 silent version of that play, which in turn provides her witches with their foreknowledge. Even as specific media mutate, the doubled consciousness of time and citation persists and complicates any single moment of performance. Her final example of such haunting disorientation involved the 1964 Gielgud/Burton Hamlet’s innovative broadcast through “the miracle of electronovision” with its rhetoric of the new and the live, even as it was designed to be televised in four synchronized showings and then destroyed; she juxtaposed this with the Wooster Group’s acclaimed use of disappearing parts of that film, creating the effect of being “marooned” in moments of time with no possibility of “pure recovery.” Like Richard Burt’s Derridean meditations on Orson Welles’s “Filming Othello” (and much more that eludes linear description), film’s visual repetitions and gaps provided an occasion for broader theorizing about what we perpetuate and miss when looking for Shakespeare in the archives. Aptly, the conference also included a full viewing of the Svend Gade Hamlet—an old favorite for some, while a new discovery for many in the group. (Alas, my late arrival precluded my hearing Alexa Huang on “Global Shakespeare and citational theatricality,” clearly of a piece with these other keynotes that have moved beyond Diana Taylor’s archive v. repertoire binarism as well as the text/performance one.)

Professor Karimi-Hakak’s talk shifted attention away from the theoretical to the deeply immediate political consequences of performing Shakespeare in different times and places around the globe. Drawing on documentaries available on his website mahmoodkarimihakak.org, he shared the story of his Farsi translation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, produced in Tehran early in 1999 but interrupted on the fifth night by saboteurs and subsequently shut down; he was then charged with “outrage against the public decorum” and his family was forced to leave the country that June. Sharing the varying perspectives and fortunes of members of the cast as recollected two years later, the documentary Dream Interrupted illustrated the unpredictable as well as familiar sources of threat and power in recreating Shakespeare’s plays, and their life-changing consequences beyond the stage. At the other end of the spectrum now that he is on the faculty at Siena College, NY, he shared through his production of HamletIRAN how he tries to help his politically sheltered students empathize with a wider world; his restaging of that play in the specific contemporary context of the Green Movement that emerged after the stolen 2009 Iranian election is recalled in the documentary Hamlet’s Green Evolution. Both these Shakespeare productions capture his more general desire to connect classics with the contemporary, seeing the ways in which past and present speak to and transform one another as unfinished, urgently ongoing work.

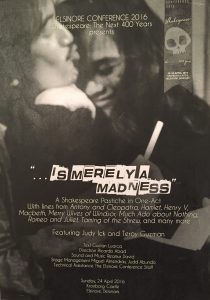

The conference not only made space for reflections upon recorded performances but also for live scenes each day, including “20 Minute Shakespeares” at lunchtime performed by students from Thornloe College and Teeside University, and, on Sunday 24th April, by Philippine professionals Judy Ick and Teroy Guzman, directed by Ricardo Abad in Guelan Luarca’s script “…is merely a madness.” Having previously seen their Macbeth and spoken on panels with them in Taiwan in 2012, I found this scholarly/performative intersection on a third continent all the more delightful an example of Global Shakespeares embodied.

Not everyone could get financial support to travel halfway across the world however, and so it was equally pleasing to see how many conferees gathered to watch a film brought from India by Santanu Das, capturing his compelling version of Macbeth as created with his students at Rabindra Bharati University in Kolkata.

On the 23rd itself, there was an evening performance of Shakespeare’s Will, the one-woman show about Anne Hathaway here performed by Joanna Purslow. And there were two other rituals of note commemorating the special day. One was a truly 21st-century innovation arranged by Ronan & crew for the conference attendees: a champagne toast shared with colleagues and performers around the globe via Skype, with participants in Russia, South Africa, Canada, Korea, and India. The other was more in the spirit of creative anachronism and had been organized not at all for us, but rather for the local and national Danish community as well as their international visitors—that is, the much larger voluntary public celebrating Shakespeare 400.

Thus it was (due to the generosity of my panel’s organizer, Anthony Guneratne) that I found myself on the mythic night at a Danish-dominated formal banquet in the castle’s long dining hall, at the “Gertrude table” festooned with red rose petals and lipstick-stained bits of fabric strewn around towering centerpieces of marzipan. (I felt fortunate to be there and not to be, as some of our number were, at the plastic-rat-adorned Polonius table, or indeed the skull-laden Hamlet one.) It was breathtaking to witness principal dancers of the Royal Danish Ballet execute the lovers’ pas-de-deux from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet at such close range in a perilously small central area; delightful to hear a recitation of “To be or not to be” alternating between Danish and English by a Guildhall-trained Danish actor; and fascinating to be educated by local residents about other esteemed Danish actors and musicians. One woman in period garb fainted before the third course, but we were told not to look to the lady, rather sternly: I suspect this was seen as an embarrassment by our otherwise informative tablemates. In any event, I had a panel the next morning and left well before the carousing concluded, the sounds of merriment echoing as I padded gingerly down the cobblestones in the darkness, giving further fuel to Hamlet’s national stereotyping about deep drinking…

The panel I arose to join, on “The Future of Shakespearean Rediscovery,” had its own paradoxes and complexities which I will not attempt to summarize here: suffice to say that it carried forward some of the themes already sketched above in its mixture of archival work on Eisenstein and Olivier, theoretically informed discussion of popular works and the canon, online sites, and Italian film, and my own talk on the changing state of Shakespearean pedagogy and performance. As valuable as this and other sessions were, what lingers in my memory more vividly now is that banquet near but not directly connected with the conference—yet perhaps more indicative of why Shakespeare might indeed have another 400 years of afterlife in him. While the scholars certainly enjoyed each other’s company and witnessing performances, here the Danes (and the U.S. ambassador, and a U.S. exchange student who won a night in the castle for her essay on what Shakespeare meant to her, I later learned) were eliding the boundaries of playacting and professional craft, of historical site-specificity and sheer fantasy, with Shakespeare’s tragedy providing the scripture for creating an immersive 21st-century community. At the same time, the skull behind the castle now haunting my memory is Karimi-Hakak’s hard-bought Dream Interrupted, a ghostly resurrection chastising those who would see only a heritage Bard and demanding that we notice more of the world, its silenced and betrayed populations crying out from their purgatories, “Remember me.” We ignore Shakespeare’s actual publics and their varying perspectives and desires at our own peril.

Exit Elsinore, pursued by hail.

Diana Henderson is Professor of Literature and a MacVicar Faculty Fellow at MIT.

So, bravo, I say!