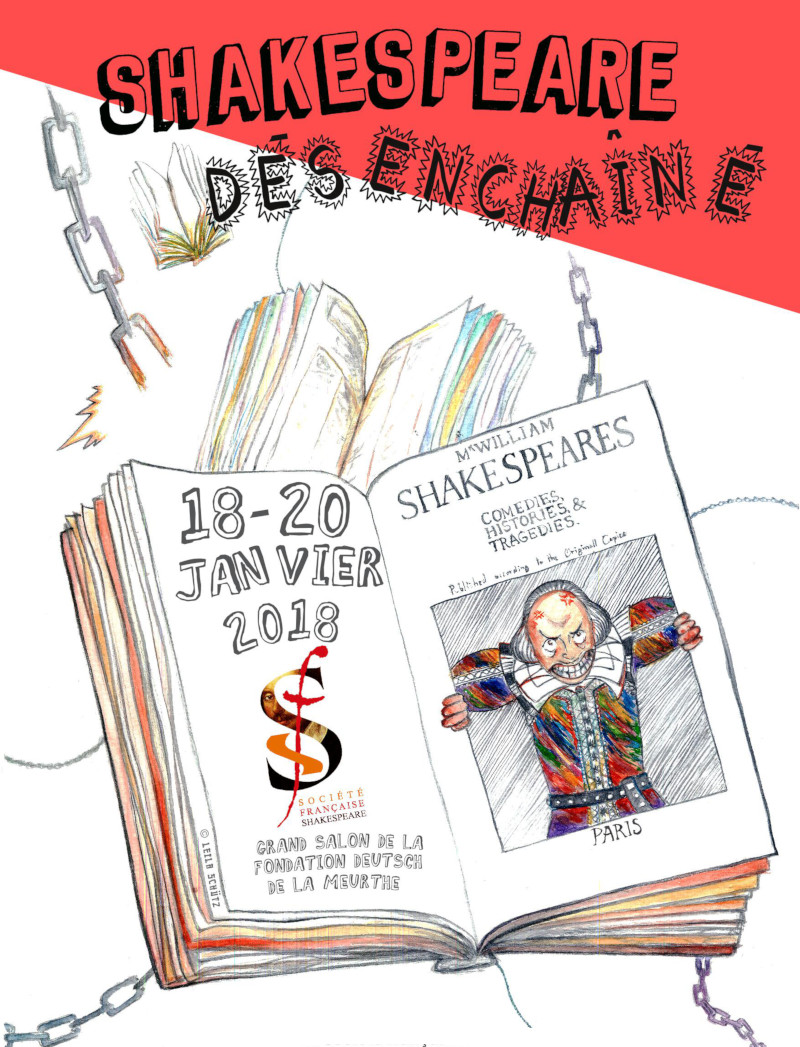

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 37 (2019)

How does Ophelia become “unbound” through supralinguistic structures of spectacle and music especially in a transgender performance? With case studies of three Hamlet films: Haider (India, 2004), The King and the Clown (South Korea, 2005), and Prince of the Himalayas (Tibet, 2006), this article examines theatrical and cinematic presentations of Ophelia’s double bind as an icon and a victim.

Read more in Alexa Alice Joubin’s new article on feminist and transgender performances of Ophelia.

==========================

The figure of Ophelia has been framed in gender-bending queer performances. Directed by Lee Joon-ik, the 2005 South Korean feature film The King and the Clown echoes various elements in Hamlet.6 The film is not a straightforward adaptation of the Shakespearean tragedy, though Adele Lee has argued that it can be seen as a retelling of Hamlet “from the perspective of the traveling players,” turning the Shakespearean tragedy inside out.7 Set in the fifteenth century Joseon Dynasty, the film depicts the homoerotic entanglement among King Yeon-san and two street acrobat performers, the macho Jang-saeng and the effeminate Gong-gil. The king hires a group of vagabond traveling players to help him catch the conscience of corrupt court officials. The film thrives on the tension between theatrical presentation (play-within-a-play in the genre of namsadang nori) and cinematic narrative (which is the fabula of the film itself). The “mousetrap” play gradually supersedes the cinematic framework to become the primary, more interesting narrative.

Of special interest is how the narrative revolves around Gong-gil, an Ophelia-like figure, whose presence is a catalyst for the twists and turns of the plot. Gong-gil, the titular clown, attempts suicide and lies in a pool of his blood. His innocence contrasts with the straight male characters’ calculation and intrigues, though his innocence also turns him into an object of male gaze.

The female impersonator Gong-gil evolves into an Ophelia figure as the film’s narrative unfolds, particularly when he wears a Beijing opera headdress in a protracted play-within-the-film scene, where the flowers on his head call to mind not only Ophelia’s flower picking and flower wreath, but also the figure of flower boy in Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan. The flower boy, or kkonminam, refers to an effeminate singer or actor whose gender presence is fluidly androgynous.

The film could be read as a political thriller or a homosexual love story. Over time, King Yeon-san, himself a composite Hamlet and Claudius figure, grows affectionate with Gong-gil who plays female parts onstage and continues to present as female while offstage. One of the king’s concubines, Jang Nok-su, becomes jealous of Gong-gil who seems to be replacing her as the king’s favorite subject, or yi. At the same time, Gong-gil’s long time street performance partner Jang-saeng also grows resentful toward Gong-gil’s special status in the court. The king is clearly drawn to Gong-gil’s appearance as an exotic object, while Gong-gil seems to hold the unhappy king in his sympathy. King Yeon-san frequently asks Gong-gil to put on private shows involving finger puppets in his chamber. As time passes, the king is enamored not only of Gong-gil’s effeminate appearance but also his pure nature and kindness, qualities that are rare among the concubines, courtiers, and officers in the king’s court.

King Yeon-san goes back and forth between his concubine Nok-su and the clown (player), Gong-gil. It is unclear what the king’s emotional needs are. In one intimate scene, the king displays symptoms of Oedipal complex when Nok-su says “come to mama, poor baby wants mama’s milk.” The king rests his head on her lap. We can see parallels to Hamlet’s self-emasculation in the act 3 scene 2 with Ophelia. In contrast to Nok-su as mother and lover, Gong-gil can be seen as the Ophelia figure as he replaces Nok-su in the king’s court.

At one point the concubine taunts Gong-gil about his “real” gender. She tries to undress Gong-gil in front of the king, creating a great deal of tension. Gong-gil does not say a word and seems rather docile in this moment when he is expected to protest the concubine Jang Nok-su’s pent-up anger. The concubine’s motives are two-fold. She is jealous of the newcomer who replaces her as the king’s favorite subject. She is also frustrated by Gong-gil’s impersonation of femininity. The king eventually uses brute force to throw her out of the room to protect Gong-gil. The concept of drag may not apply here, as Gong-gil is not only in drag when in performances but remains in female presentation in daily life. A parallel example would be early modern English boy actors’ careers. There are multiple cases of successful boy actors, such as Richard Robinson and Edward Kynaston, who played female roles on stage and transitioned to playing male roles when they grew up. Boyhood was presented as androgynous and gender fluid, but interestingly, as Simone Chess theorizes, these boy actors carried a “queer residue” with them into male adulthood as they continue to perform feminine or androgynous roles.8Kynaston is probably the best known among them in modern times thanks to Samuel Pepy’s diary (August 1660) and the feature film Stage Beauty (dir. Richard Eyre, 2004).

Like Kurosawa’s uses of traditional Japanese theatrical elements in his films, The King and the Clown draws attention to Korean theatrical traditions by frequently placing an emphasis, ironically, on the stage rather than the screen as a medium of expression. Gong-gil’s presence provides a powerful framing to the idea of the artificiality of performance—of gender, history, and genre.

—————–

Excerpted from: Alexa Alice Joubin, “Ophelia Unbound in Asian Performances.” Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 37 (2019): 1-12.

Full text online: https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4887