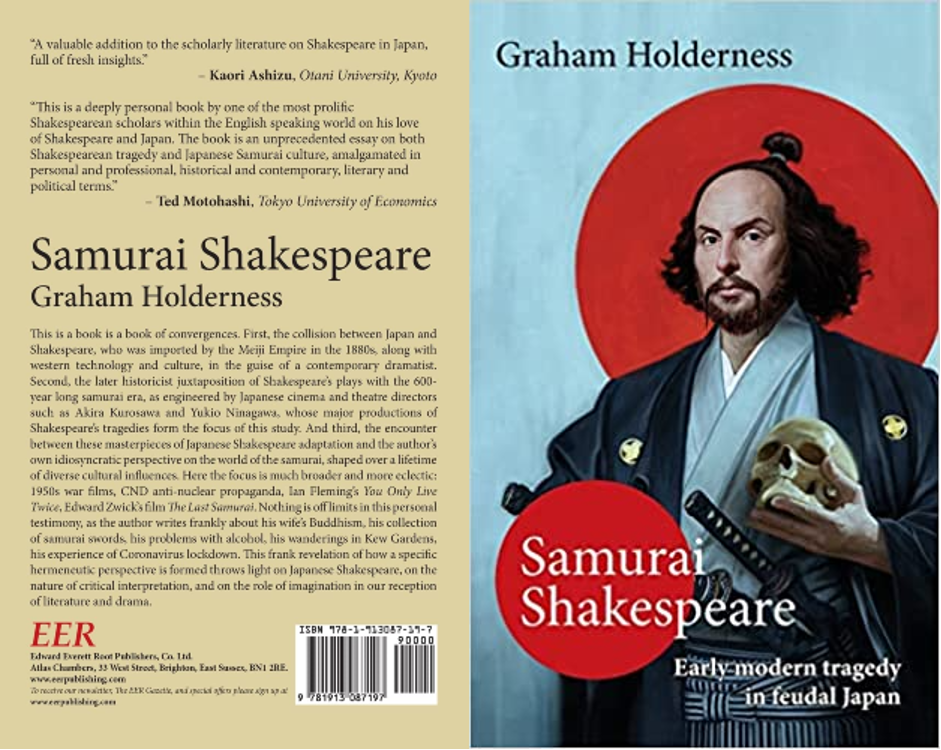

Samurai Shakespeare: Early Modern Tragedy in Feudal Japan (Edward Everett Root, 2021).

GRAHAM HOLDERNESS

This is a book of convergences. First, the collision between Japan and Shakespeare, who was imported by the Meiji Empire in the 1880s, along with western technology and culture, as a contemporary dramatist. Second, the much later historicist juxtaposition of Shakespeare’s plays with the 600-year long samurai era, as engineered by Japanese cinema and theatre directors such as Akira Kurosawa and Yukio Ninagawa, whose major productions of Shakespeare’s tragedies form the focus of this study. As the book shows, after initial attempts to import Shakespeare whole, partially to endorse and support a project of westernization – which resulted in a collision between classic English drama and Japanese theatrical traditions – the Japanese began to find their own ways of accommodating Shakespeare into native conventions, and eventually resolved this cultural clash by generating adaptations that satisfy both eastern and western tastes and sensibilities. They did this largely by recognizing that relocating the plays back into the feudal past brought to light commonalities between Shakespeare’s sense of history, and Japanese perspectives on their own social and cultural traditions.

A chapter on Hamlet pursues the intriguing parallels between Shakespeare’s tragedy and the Japanese legend of the 47 Ronin, examining the 18th century bunraku play Kanedehon Chushingura, Harue Tsutsumi’s play Kanadehon Hamlet, and Carl Rinsch’s film 47 Ronin. The specifically Japanese engagement with its own past is addressed through several productions of Hamlet directed by Yukio Ninagawa. Parallel revenge conventions are aligned and compared in Shakespeare’s text and in Tai Kato’s cinematic version of Hamlet, Castle of Flames.

The Macbeth chapter revisits Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood and Ninagawa’s Macbeth, showing that both express an authentically Japanese spirit while simultaneously offering intelligibility to western audiences. A chapter on King Lear focuses on Kurosawa’s film version Ran, challenging the critical consensus by proposing a much stronger presence of Buddhism in the filmic text. Textual analysis ranges across the filmic medium, the Shakespearean text and published shooting scripts. Each chapter supplement the Japanese resources with a direct approach to the Shakespearean text, highlighting those aspects that interact most creatively with Japanese appropriations.

The academic dissertation is framed by chapters of a more personal kind, exploring the convergence between subject and object, highlighting the role of the interpreter alongside the body of interpretation. These sections discuss the problems and possibilities of writing about Japan having never visited the country, compelled to construct what Roland Barthes identified as a ‘fictive world’, or what the author calls an ‘ukiyo’ or ‘floating world’. Here the author writes frankly about his early encounters with Japan via western media – 1950s American war films, CND anti-nuclear propaganda, Ian Fleming’s You Only Live Twice, Edward Zwick’s film The Last Samurai. Nothing is off limits in this personal testimony his wife’s Buddhism, his collection of samurai swords, his problems with alcohol, his wanderings in Kew Gardens. This frank revelation of how a specific hermeneutic perspective is formed throws light on Japanese Shakespeare, on the nature of critical interpretation, and on the role of imagination in our reception of literature and drama. And third, the encounter between these masterpieces of Japanese Shakespeare adaptation, and the author’s own idiosyncratic perspective on the world of the samurai, shaped over a lifetime of diverse cultural influences. A collection of photographs illustrates how the author managed to construct his Japanese ‘fictive nation’ under conditions of Coronavirus lockdown, drawing images from Japanese landscapes and structures in Kew Gardens and Holland Park: a 17th century sword in his possession bearing the crossed hawk feathers of the Asano clan; a blossoming Asano cherry tree outside his house in West London.

The constituent elements of the book can be summarised as: a personal interest in the history of Japan, and an enthusiasm for stories of the samurai; a professional engagement with intercultural exchange, the ways in which English classics are absorbed into a foreign culture, and a historical investment in the specific example of Shakespeare’s arrival in Japan in the late 19th century – hence an excusive concern with adaptations of Shakespeare that set the plays back into Japanese history, usually the Sengoku period. The book attempts to show that the ambivalent view of the samurai with which the author grew up grew up is as Japanese as it is western, visible as early as the epic poems and historical chronicles that created the legend of the samurai in the Middle Ages, and crystallised into an urgent national debate at key moments of Japanese history, such as the Meiji Restoration and the end of the Second World War. Were the samurai romantic heroes, or tyrants consumed by ambition? Were they the saviours of the nation, or enslavers of the people? Were they, as Jonathan Clements puts it, ‘blinkered fools who opposed modernization in favour of an impossible mediaeval time warp?’ Or did they represent rather ‘the indomitable will to reform, which led the opponents of the Tokugawa to topple the shogun, restore the Emperor are last and modernize Japan as his willing “servants”?’ (Clements 2010, 318) These controversies are actively and energetically put to work in the Shakespeare adaptations studied in these pages: hybrid, intercultural works of art which prove to be as consistent with our own western engagements with Japan, as they are true to the spirit of Japanese culture.

http://www.eerpublishing.com/holderness-samurai-shakespeare.html

https://www.amazon.com/Samurai-Shakespeare-Future-Japan-Theatre/dp/1913087190