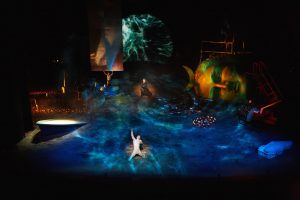

Yohangza Theatre Company’s Pericles directed by Yang Jung-ung in 2016. Photo originally published at Performance Shakespeare 2016 Blog.

The World Shakespeare Congress is often referred to as the Olympics of Shakespeare studies. This year’s “Shakespeare Circuits” theme fully embodies this Olympic metaphor as it invites multiple circuits of diverse knowledge and experience to intersect. It was refreshing to hear and join dialogues between familiar and unfamiliar names in the field. This is definitely one of the upsides of virtual conferencing. Luckily, the WSC also recorded most sessions and performances, which allowed me to shuffle through the recordings at my own pace, while enjoying some of Pek Sin Choon’s delicious tea. I particularly enjoyed Yang Jung-Ung’s thoughtfully narrated production of Pericles (with a silent Pericles in a grandiose stage) that blended theater and film aesthetics. And I found Owen Horsley’s innovative use of a cubed stage on the stage in Henry V as a clever way to mark setting changes and more importantly, social difference and convergence. Most performances are still available for viewing on the platform for a short time, in case you missed any of them.

Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre’s Henry V directed by Owen Horsley in 2016). Photo originally published at Royal Shakespeare Company.

This was my first time participating in the WSC. I was part of the “Global Shakespeare and Cultural Diplomacy” seminar hosted by Anne Sophie Refskou, Nathalie Rivere de Carles, and Naoko Shimazu. In our seminar, Donna Woodford-Gormley explored how Shakespearean productions like the Merchant of Venice and A Midsummer Night’s Dream have been used to bridge the gap between Cuba and the U.S. Similarly, Helen Hopkins investigated the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust as a site of long-term and ongoing international cultural diplomacy, especially between China and England. And my own contribution examined online cultural diplomacy in international festivals like the 2012 Globe to Globe, through the online interactions of the Albanian II Henry VI production. This fervent discussion prompted all of us to consider the need for a more concrete definition of Shakespearean cultural diplomacy. Although this is all still work in progress, I’m confident that identifying and understanding cultural diplomacy will be beneficial for navigating all Shakespeare circuits.

I kicked off WSC with Dennis Kennedy’s keynote speech on “Shakespeare’s Refugees.” Kennedy explains that Shakespearean characters travel through forms of exile. He uses this umbrella term to discuss banished characters who are altered by their journey, and their genre-based returns (if they indeed return) result in restoration, renovation, disaster, or it is only imagined. Kennedy looks at Peter Stein’s 1977 production of As You Like It—one of the most popular banishment plays—performed in Berlin. The actors transition from the white space of the court life through a tunnel that leads to the pastoral life, and the spectators experience the same banishment as they are prompted to follow too. But in the end, they cannot return back, and they’re stuck in between the two worlds. To further cement the significance of exile in Shakespearean plays and performances, Kennedy also turns to Ninagawa Yukio’s 1987 Tempest, which was produced in Sado Island—a historical site for political exile. Kennedy’s speech and the exemplary productions open a dialogue about the history and future of Shakespeare in geopolitics and immigration.

On the other hand, Preti Taneja’s keynote speech took a more direct approach on Shakespeare’s future. Taneja introduces the idea of fascism as a spectacle through her modern translation of King Lear in Indian, called We That Are Young. Taneja calls on the present pandemic moment to point out the ways in which Shakespeare seeps into political rhetoric of India, UK and U.S. government leaders to create spectacles—performances of justice. This rich speech inspires younger minds to act and not simply imagine the deconstruction of fascist spectacles.

Sandaime Richard directed by Ong Keng Sen in 2016. Photo originally published at The Strait Times.

Meanwhile, I’m still combing through the recorded keynote speeches which I couldn’t see live. I’m excited to hear about Ong Keng Sen’ production of Richard III which queered the stereotypical representation of the hunchback Richard to an unhappy queer. Likewise, I look forward to catching up with Tang Shu-Wing’s speech on Shakespearean dramaturgy and how the human body in performance can narrate a story without external assistance. I’m grateful practitioners, scholars, creative writers, and educators came together in this event to discuss Shakespeare from all places and angles.

I’ll close my remarks on the 2021 World Shakespeare Congress by mentioning one of my favorite moments: the “Gender and Sexuality: The State of the Field” roundtable hosted by Valerie Traub. The inspiring works and conversation between Alexa Alice Joubin, Judy Celine Ick, Kumiko Hilberdink-Sakamoto, Madhavi Menon, and Marjorie Rubright highlight the transitive role of gender and sexuality, especially in Asian theatre and the many ungendered languages of Asia. The speakers remind us that pronouns are not always adequate markers of gender identity but engaging in the plurality of pronoun politics is what the field needs. That is all to say that Shakespeare’s circuits are driven by languages that open multiple possibilities for meaning.

Additional photos

Yohangza Theatre Company’s Pericles directed by Yang Jung-ung in 2016. Photo originally published at Performance Shakespeare 2016 Blog.

Yohangza Theatre Company’s Pericles directed by Yang Jung-ung in 2016. Photo originally published at Performance Shakespeare 2016 Blog.

Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre’s Henry V directed by Owen Horsley in 2016. Photo originally published at Royal Shakespeare Company.

Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre’s Henry V directed by Owen Horsley in 2016. Photo originally published at Royal Shakespeare Company.

Marinela Golemi is a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow at the United States Military Academy. She has also taught Shakespeare and Early Modern English Literature for the Department of English at Arizona State University. Her research interests include local and global Shakespeares, Shakespeare in Albania, and Early Modern Drama.