by Colleen Kennedy (PhD Candidate in English, Ohio State University; kennedy.623@buckeyemail.osu.edu)

1. Shakespeare Must Die was the first and only film to be partially funded by the Culture Ministry’s Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (under Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva). Was this an optimistic moment for the arts? Are there any art projects funded under the new administration of Yingluck Shinawatra?

At least 50 other film projects received this funding. Some for script development, some for production, one for distribution (The 2010 Palme d’Or winner ‘Uncle Boonmee’). Recipients include studio films as well as independent films. In fact the studio films got the lion’s share; the amount also varied greatly. For instance, out of the 200 million baht fund, one big epic, ‘The Legend of King Naresuan’ received 49 million; and ‘Headshot’ by Penek Rattanaruang got at least 8 million. Most received between 5 and 1 million. Our 3 million is therefore on the lower-middle end. (30 baht = 1 USD)

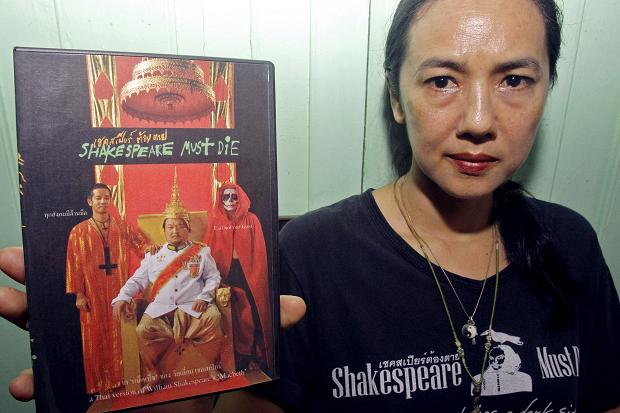

So no, ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ is most definitely NOT the only film funded by the Abhisit government’s film fund under the Creative Thailand Fund (the Thai name, Thai Khem Khaeng Fund, literally means “Fund to Strengthen Thais”. For industrial applications, to increase the value of goods by improving the design; for cultural and educational projects, to stop the dumbing down of the population). ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ was in fact the very LAST film to receive funding (though not the last to be finished; many other projects remain unfinished at this time, August 2013) , as some funding committee members were concerned about our depiction of the regicide scene.

(A few years back, Bangkok Opera got into absurdist trouble with the Cultural Ministry over its production of the ‘Ramayana’. They were told not to portray Rama’s slaying of the Demon King on stage. He might be a demon, but he was still a king, went the argument. The Ramayana! They were not banned from doing so, but would not be allowed to use the Ministry’s prestigious venue. The ministry claimed that it was against tradition to kill a king on stage. This is entirely false. I distinctly remember seeing this very scene on stage at the National Theatre. This shows how unpredictable it can be. The film ‘Suriyothai’, a historical epic, has very graphic scenes of regicide.)

So we had to shoot the scene and show them all the uncut footage before they would approve our funding. No other applicant had to do this. Everyone else only had to submit a synopsis and treatment. We told them that we would stick to Shakespeare’s staging of the scene, namely, that everything happens off-stage: all we see are their bloody hands, all we hear are their thoughts. Just as Shakespeare intended, I believe, since the focus is not the murder but its effects on the Macbeths, before and after.

After viewing this footage, they were convinced of our Shakespearean sincerity, some even commending that it was in fact a moral undertaking because it “explores the nature of sin and karmic retribution”.

Therefore, far from being a ‘propaganda film funded by the Eton and Oxford-educated Evil Elite Royalist Abhisit to make fun of Champion of Democracy Thaksin’, as claimed by Thaksin apologists, ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ was actually the most scrutinised film and barely received the funding at the very last minute.

The Democrat Party is highly unlikely to choose me as their propagandist! My first fictional feature, ‘My Teacher Eats Biscuits’ was banned in 1998 by the Democrat government, Abhisit’s party (though he was just an MP, not the PM at the time). Unless you’d insist that by revealing the truth about the tourism/real estate and golf course industries, I made green propaganda films, I can honestly, and proudly, say that I have never made a propaganda film. Most other Thai filmmakers have, including well-known festival darlings who now portray themselves as anti-royalist and therefore democratic. Even Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Penek Rattanaruang have made government-funded films extolling the king. (Not part of the same film fund but a series of shorts funded by the Cultural Ministry to glorify the king’s 60 years on the throne, a project called ‘Nhang Nai Luang’—“The King Movies”, a way to make propaganda sound cool, with cool shorts from cool filmmakers.) No one would dream of approaching me to join such projects. I just wouldn’t do it. It would make me physically ill. Nothing against the king, but such overkill glorification is detrimental to society and the monarchy itself. I think such projects only provoke an understandable backlash.

The Creative Thailand film fund was the first and last of its kind, open to all types of film and filmmakers, without a stated theme (such as to extol the king or save the environment). It no longer exists; the Yingluck government has no film fund. It’s not very interested in our mental improvement.

2. Why did the Ministry of Culture fund this particular film? Did you apply for funding? Were you approached by the Culture Ministry? If the latter, why?

Please see above. No, we were not approached; we were in fact barely tolerated!

3. Even before Shakespeare Must Die, you were known as a provocative filmmaker. Your documentary titles Thailand for Sale (1991), Green Menace: The Untold Story of Golf (1993) and Casino Cambodia (1994) all demonstrate your ability to highlight and portray the problems of Thai society. Your film My Teacher Eats Biscuits was banned from a film festival for its “depravity.” How does Shakespeare Must Die fit into your oeuvre?

I switched from print journalism to filmmaking because I needed to show rather than tell. As the first writer to focus on environmental problems in Thailand, at a time (1980’s) when the environment was not yet considered real news in the world, I often encountered scepticism and antagonism from editors. They just wouldn’t believe that things could be so bad.

The advent of Hi 8 video made filmmaking accessible to outsiders like me. ‘Thailand for Sale’ (which I wrote and narrated but didn’t direct, for the BBC and the Television Trust for the Environment) and ‘Green Menace’ are obviously straight-forward visual extensions of my green investigative journalism. ‘Casino Cambodia’, initially about Cambodia becoming a casino for the world’s speculators as armed conflict ended, came from my further past as a UNHCR volunteer in a Cambodian refugee camp on the Thai border. Ultimately, it poses the question: who gets the right to write the accepted version of history? Henry Kissinger is not demonised like Pol Pot; instead he gets the Nobel Peace prize–why?

‘My Teacher Eats Biscuits’ seems a weird departure from all this seriousness. It was my experiment to make a 16 mm film with a very low budget; it was actually the first independent Thai film, made by people totally outside the system. I wrote a script around what I had or what I could beg and borrow, so my dog became the arch villain, a sacred dog worshipped as His Holiness in a New Age ashram. I wanted to examine the nature of rationalisation, of worship and belief. I had the mistaken trust that a comedy would get away with more. It turned out that people get even angrier when you make them laugh in spite of themselves.

In the above list you left out ‘Citizen Juling’, my documentary about the unrest in the Muslim-majority South of Thailand, which centred on an idealistic young Buddhist teacher from the North who volunteered to teach art in the war zone of the south and was beaten into a coma, apparently by enraged Muslim housewives (untrue—turns out they were male terrorists in burqas). This film, permeated with a terrible sense of loss, consumed me with its grief, and when it was rejected by every documentary festival under the sun, the only way I could deal with it was to set myself an overwhelming task, my version of a Herculean labour, namely to translate ‘Macbeth’ into Thai. The sheer difficulty (perhaps impossibility) of it would leave me with no idle brain space for unproductive thinking.

I thought it would take years. But the task gripped me utterly and after locking myself away for four months, not just the straight translation but the whole script was done. (Oddly, as soon as this was done, ‘Citizen Juling’ was invited to Toronto and Berlin Film Festivals out of the blue.) ‘Macbeth’ as ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ is a totally natural outflow, of blood and tears if you will, from our conversations with the grief-stricken people of the South, Muslims and Buddhists, who have suffered most from Thaksin’s rule by fear and violence.

While Thaksin’s crimes did inspire me to reread and then translate the world’s best-known study of tyranny, in my mind were also all the local mafia figures in nearly every Thai village who rule with fear. Thaksin is just their overlord. According to Human Rights Watch researcher Sunai Phasuk as well as other sources, Thaksin (who had been a police colonel—he studied criminology in Texas–before becoming a telecommunications billionaire and then politician) achieved his monopoly on Thai tyranny by getting rid of all opposing local influential figures, many of whom were local canvassers for other political parties, through his War on Drugs, which killed at least 2,500 people in police-perpetrated extra-judicial killings, including women and children. My killing of Lady Macduff and her child comes straight from this: the official-looking checkpoint on a lonely road at night, the menacing group of men in uniform-like safari suits. Thaksin’s (and his wife’s) well-known interest in the occult is by the way; all tyrants seem to share this supernatural interest: Hitler, Idi Amin, Hun Sen, Burma’s Than Shwee, you name it. It’s hard to find one tyrant who was or is not into the occult.

I first encountered ‘Macbeth’ as a 15 year old at school in England. My English was barely serviceable at the time. But the play has haunted me all my life. Tyranny in the form of bullies is a fact of most people’s life; my own childhood was rich with them, so they have always fascinated me.

4. Graiwoot Chulphongsathorn claims that you are denied your rightful place as a Thai filmmaker, as a female director, and as director of cult films, and goes on to compare My Teacher Eats Biscuits to John Waters’ Pink Flamingoes. Could you comment on the following description of your film?

I now realise that to call My Teacher Eats Biscuits a dangerous, depraved film, is the equivalent of the Thai government accusing Pink Flamingoof national treachery, or of clinging to the logic that the films of Paul Morrissey have the power to destroy religion.That’s because My Teacher Eats Biscuits is a ‘cult’ film in the spirit of John Waters. It’s low-budget, stars friends of the filmmaker, and is shot in the back of somebody’s house. The resulting film is one that had myself and a group of friends helplessly laughing every five minutes when we finally got to see it.

Was this film ever officially released? What is the status of this film?

I do love John Waters. He showed me and other guerrilla filmmakers of my generation how it was possible to make a film without real actors and with very little money. The key is to write dialogue that would sound funny even when recited, deadpan. I didn’t consciously copy ‘Pink Flamingo’ otherwise, except perhaps to force my lead actor (now a bona fide movie star but this was his first movie) to eat dog shit (actually just mashed up candied durian). The film has not been released. It exists as one 16 mm print. It premiered at the Hawaii International Film Festival before it was banned.

Many people have suggested that I should resubmit the film to the censors. That would have to wait for the end of the ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ and ‘Censor Must Die’ struggle. It would be too exhausting otherwise. However, along with the fact that these are the worst times for Thai freedom of expression in my living memory, it’s unlikely to pass for a very odd reason. In recent years, some ultra-royalists have taken to wearing pink to show their love for the king. The ashramites in the film wear pink and kowtow to a dog. They might even say I’m depicting the king as a dog, even though this film was made years before all this colour-coded nonsense. My actors wear pink because it’s the Ashram of Boundless Love. If they had worn red, no doubt they’d say I’m depicting Thaksin as a dog. When people see everything through the prism of propaganda, you can’t win; to argue with them is a total waste of energy.

Last year someone suggested to the National Film Archive to include this film, the first shoestring independent Thai film, in their list of national film heritage, but their committee rejected it. Not serious enough, probably.

My style does seem to change from film to film, because surely the style must serve the story. I work with the limitations that I have and make them work for me.

5. Can you tell us briefly about Shakespeare Must Die? Why use Macbeth as your source? What is it about Shakespeare that transcends time and space?

As for the title, Shakespeare must die because true artists (as represented by Shakespeare), by their very existence, threaten tyranny’s sense of security by shaking their flimsy constructs and versions of reality; by tyrants I mean those who would rule the world with fear and lies.

The film’s use of the Shakespearean play within a play device is appropriate as well as being affordable. It would’ve been delicious to have tanks in the streets, helicopter shots of Macbeth on a penthouse terrace over the Bangkok skyline at sunset etc., but that is not within our reach, so I couldn’t write that script. Cheap swords on a stage would have to work somehow, and the only way for that to work is to stage such scenes on a theatrical stage. The fake theatrical violence then serves to emphasize, by contrast, our bloody ending of a realistic lynching (of the play’s director) with echoes of the bloodiest chapter in contemporary Thai history (October 6 massacre in 1976, when a mob, incited by lying propagandists to become enraged by a protest play at Thammasaat University, massacred student protesters, Rwanda-style—some girls were staked through the heart like vampires. At least I didn’t depict that—perhaps I should have. I do imply it with a brief shot of two girls backing away from a threatening group of men.)

Shakespeare transcends time and space because, one: he’s just so damned good, regardless of all this clever postmodern deconstruction, this plague of pseudo-intellectual profundity in contemporary art today, any truthful person can recognise truth and beauty (as in John Keats) when they experience it; two: his subject is the human soul and he has the gift of ecstasy; three: he deliberately and joyously plays with time and space, through his sudden gear-shifting from one dimensional reality to another without any warning nor excuses; his trippy visuals; his synaesthesia; his magic (literally, as in invoking, incantational power), so much so that his world view, or view of the whole cosmos, is more akin to quintessential Hinduism, Buddhism and Sufism than his own cultural context of social Christianity. Naked Hindu mystics on the banks of the Ganges are more likely to understand and relate to Shakespeare than the average Englishman today. His structural reality (and lack thereof) is universal, therefore. To me, Shakespeare is not only a poet, the poet, of unimaginable power, he is also a prophet, as great or greater than most accepted religious and philosophical figures. (Now you see why I should be burned at the stake.) His art leads us to self-knowledge and divine communion in the deepest sense.

While I was astonished that it took me only four months of total immersion to translate ‘Macbeth’ into Thai, I soon realised this was because there is something innately universal, quintessential, about his music, his rhythm, his very sound. Like the Hindu mystics (and the bible, actually), I do perceive the physical universe as the manifestation of sound: “OM”; “the music of the spheres”; “In the beginning was the word.” That’s why I worked so hard to keep Shakespeare’s sound. Interestingly, I had terrible problems with some passages, which I later found were suspected by some to be later additions to the original play.

6. Is Shakespeare an aspect of the Thai educational system? Are there Shakespearean theatre companies or other cinematic adaptions of Shakespeare’s works popular in Thailand? How and why does Shakespeare speak to or for modern Thailand?

Shakespeare is part of the syllabus for the last two years of high school, but only for those on the liberal arts course rather than the sciences. They learn from King Vajiravudh’s (first world war era) translations of ‘Merchant of Venice’ and ‘As You Like It’. (This was a man who should’ve been a writer/poet rather than king. He was a genuinely gifted poet but he bankrupted the country.) They are not direct translations but ornately rendered into a very rigid form of Thai poetry called the verse of eight. It’s a virtuoso performance, a genuine achievement; one particular part (“The quality of mercy is not forced…”, which he translates as “Un Kwarm Garuna Pranee/ Ja Mee Krai Bangkup goh hamai”) has entered the stream of common usage, but nothing else has. We can’t relate to it because it doesn’t sound like speech. It’s not easy or natural for actors to say. He directed and even performed in them himself at court, using not real actors but his intimate circle; the performances were not for the public. They haven’t caught on despite being part of the high school syllabus.

Real Shakespearean studies exist only at university level, where they actually study Shakespeare’s original texts.

No, there are no Shakespearean theatre companies, though one theatre group recently staged a loose adaptation of Lear called ‘Lear and His 3 Daughters’. Chulalongkorn University (the Thai equivalent of Harvard)’s Liberal Arts School staged the only nearly full-length (cutting out the ‘boring’ and problematic ‘English scene’ with Malcolm and Macduff which discusses the divine right of kings) performance of ‘Macbeth’ while we were still editing our film, using our Macduff as their Macduff and our Macbeth as their Lennox. It was directed by one of their lecturers, Noppamas Waewhongse (not sure about the correct spelling, just a straight transliteration), who used her own translation, which she did years ago. Since it hadn’t been published, I wasn’t aware until I was casting the film that there was already a translation by a Chula liberal arts professor. The actors told me about it. Macbeth had been an obsession of hers for years; I met her once and her joy in it was obvious. A news talk show tried to use her to discredit me, but they didn’t expect us to get on so well, because of our common obsession.

They put us together on TV, to find out why her play was attended by the king’s daughter and upset no one, while my film was doubly banned (once by the censors then by the actual Film Board). She said it was because she stuck to Shakespeare and set it in 11th Century Scotland, with authentic armour and costumes. I said if I were to do that, I’d have to shoot in Scotland, the budget would be extreme, and besides there would be no point. Those films have been made; they’re not my story to tell.

My aim was to make an emotionally and spiritually authentic ‘Macbeth’, that brings the joys of Shakespeare to Thai people who must at the same time be able to relate to it. That’s why I changed Norway, England and Scotland to censor-taunting obvious mythic names from the realm of poetry and fantasy like Shangrilla, Atlantis and Xanadu. This is very much a Thai folk opera tradition. (I love ‘likay’, or Thai folk opera. They’re travelling theatre groups equipped with not much more than two canvas backdrops, usually one of a throne room and one of a forest, with singers/dancers/actors in fantastical sequin-encrusted costumes, including since the 19th century Western ballgowns and Napoleonic coats. I took liberally from likay but, since I was making a Shakespearean film for Thai people rather than to seduce international curators, decided against the outright exploitation of such Thai exotica as it would get in the way. For, say, Midsummer, it could be fun.

Thailand, or Siam by its true, pre-fascist name, is nearly unique historically in that it was never colonised by Western empires. (Don’t worry, the West got its revenge on the king who kept them off his land by caricaturing him as Yul Brynner, Rex Harrison and Chow Yoon Fat in Hollywood and on Broadway.) Indian society, for instance, has a close relationship and familiarity with English literature, especially Shakespeare.

Most Thai people do not speak a second language. Shakespeare is heard of as a name, a ‘high-end brand’, like Gucci or Chanel. That’s why it was so exciting to attempt such a challenge, in the most ideal conditions, impossible elsewhere, to perform Shakespeare with actors who would speak every word “as if for the first time”. One girl looked up from the script after trying out for Lady M and said, with genuine wonder, “Oh my God, what a character this woman is. I love her. I’ve never seen such dialogue.” (She was reading “The Raven himself..” and “I have given suck..dash the brains out.” Alas she did not get the part.)

‘Shakespeare Must Die’ is the first and so far only Thai cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare. But because of the ban and no one has seen it, you really have to say there’s been no Thai Shakespearean film and there won’t be any if the court decides against us.

The appeal of Macbeth to the Thai public is obvious. We are living under a real live Macbeth, albeit one with an army of international spindoctors; we are living through Shakespearean times and the world beyond our borders does not know it. High drama in the streets, in the courts, in parliament, everywhere we go. Rage and hatred, operatic villainy, extreme fear and violence, spindoctors staging obscene plays within the play, piling lies upon lies, you name it. The play also contains, in the so-called ‘English scene’, a discussion on the divine right of kings, of leaders and rulers of men, which is the discussion we desperately need now.

I’m quite unrepentant. I went in with my eyes open, fully aware of the sensitive nature of my choice of play. Its relevance is the very reason to do it. It’s absurd that we’re not allowed to film a play that’s taught to 15 year old school children in English-speaking countries all over the world. It would be obscene to surrender to such a silly fear, even if—surely, especially when—the threats arising from this silly fear are very real.

7. Shakespeare Must Die is labeled a horror film. Can you elaborate? Is Macbeth a horror story? Is your adaptation more apt to be labeled horror? How so?

Like many people, I think Macbeth is the archetype of the horror genre. (The Odyssey is full of monsters, it’s true, but it’s an adventure story rather than a horror story, the blood wedding notwithstanding.) On the surface witches, dark prophecy, hallucinations, apparitions and the slaughter of innocents; then beneath that exotic manifestation we have the real horrors of spiritual corruption, guilt, insanity and torment, the ultimate horror being of course the loss of his “eternal jewel”. As the first Thai version of Macbeth, for an audience that’s mostly never heard of it, I felt the film had to deliver the eye of newt and toe of frog, both as gleeful Hallowe’en fun and as a device to emphasise, by contrast, the true horror of the Macbeths’ disintegration, again as I believe Shakespeare intended. Witches for a laugh and Lady M for shivers.

To be honest, I’d always longed to make a horror film. People have often told me that all my films including the dog-god black comedy have been horror movies at heart. As a horror movie junkie, I’m not offended. It is a genre that allows free exploration of the soul; heaven and hell, good and evil. Sacred texts like the Ramayana is at times a horror epic, not least because the hero makes his wife walk through fire to prove her fidelity. The bible has incredible horror scenes. It’s not a genre that’s taken seriously because it’s so enjoyable.

8. What are your inspirations or filmmakers (especially Shakespearean) you consulted when working on this project?

One major source of inspiration for ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ was TV melodrama: Thai soap operas and Mexican telenovelas gave the film its look and vibe (though with Caravaggio colours and lighting). This makes it instantly accessible for the soap-addicted Thai audience. The shock is also greater when it is delivered through this familiar guise. Where they expect mental comfort food served by vacuous TV stars mouthing inane TV scripts, they get, instead, powerful actors speaking Shakespeare’s intense words.

For its inner truth, I decided to trust the text unreservedly, no matter how unfashionable or scary that might turn out to be. I tried to be as free of preconceptions from existing Shakespearean cinema as possible, and did not show any Shakespearean film to my cast and crew. I didn’t want them to try to sound ‘Shakespearean’, but just to revel in the actual text. This was easier than it sounds as I haven’t actually seen that many Shakespearean films. I suppose my favourite Shakespearean film would be the Richard 3rd film set in 1930’s fascist England starring Sir Ian McKellen. I love Kurosawa’s Lady M, and the opening scene of Polansky’s ‘Macbeth’, with the witches spitting into a noose on a Scottish beach. I’ve been told that Orson Welles’ version is the only one that doesn’t delete the ‘English scene’, and I’d love to see his treatment of it, but I haven’t seen it yet.

9. How can a 400-year old Shakespearean play cause such controversy? Now? In another country? Can you comment on the censorship concerning depictions of the Thai monarchy?

I’ll answer the last part first, as it’s crucial to understanding. ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ was not banned out of fear of the monarchy. It was banned out of fear of Thaksin Shinawatra.

As I explained earlier, we had to show uncut footage of the regicide scene before they’d fund us. They even praised the footage and greenlighted the money. That was under the previous government, a ‘royalist government’. So the Yingluck Shinawatra administration could not, cannot, use that old chestnut against us. The incredible scrutiny, meted out to no other film project, that we received from the Cultural Ministry during the funding process has turned out to be a blessing. Because of it, this government was robbed of its favoured tool, Article 112 or Lese Majeste law, which the Thaksin juggernaut exploits to burnish his ‘democratic’ credentials while soiling the king with a tar brush. Even so, as the ban made international news, Thaksin’s spindoctors did their best to portray that it was banned because of the king. You can read their handiwork in the news slant. It didn’t matter what I said, the story was already written to fit the Thaksin script. As a former journalist, I knew that, but there was nothing I could do about it.

I am not fond of Article 112; my family has suffered greatly from it, has even joined a campaign to amend this law. Now that it has become a much-abused political tool, all true reformers have been forced to retreat; we’d just get lumped in with Thaksin’s red shirts. Deliberate Thaksinite provocations (such as by uploading on YouTube a picture of the king with someone’s feet above him, which provoked the predictable hue and cry to force the Abhisit government to object and thereby appearing to be less ‘free’ than Thaksin) have also caused ultra-royalists to become hyper-sensitive. When Abhisit, as PM, said 112 should be amended, their reaction was so strong that he instantly retreated and has not mentioned it again. All thinking people in Thai society are stuck between Scylla and Charybdis.

The greatest irony is the king himself has publicly spoken against this law, on TV, broadcast nationally, on record. But never mind him. Things that deviate from the script must not exist. Like the film censorship law which was ostensibly designed to protect the public from social poison but ends up harming the people by blind-folding them, the lese majeste law is meant to protect the monarchy and therefore national unity (as in “The king and the land are one so the king can/must do no wrong”), but its effects have been to harm the monarchy and divide the land. Who is the beneficiary?

The old divide and conquer strategy has been as fruitful for Thaksin and his corporate colonial cohorts as it was for the Western colonial powers in these savage lands. Thaksin would be the last to desire the amendment of Article 112. The knee-jerk reactions of ultra-royalists play straight into his hands.

The simplistic script as written by his spindoctors, and as slavishly followed by the international press, is this: Thais are not individuals with our own thoughts; Thais can be divided neatly into evil elite royalists and brave Thaksin democrats. People like me are inconvenient to such spin, so we cannot be allowed to exist. Thus ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ is banned not only domestically but, through such spin, internationally. A business tycoon first and foremost, Thaksin thoroughly understands and exploits ‘soft power’; he’s smarter than the Iranian mullahs. I may not be in jail like Jafar Panahi, but in some ways I’ve been more banned than even him.

Thaksin’s best known spindoctor is Lord Tim Bell, whose most celebrated client was Margaret Thatcher. (This is why our fembot clone PM Yingluck was celebrated as one of the world’s great women by Newsweek, alongside Aung San Suu Kyi and Hilary Clinton.) I’m sure this is why BBC and CNN didn’t touch the story of the banning of Shakespeare in Thailand, though Al Jazeera covered us twice. This is why the AP wire story was removed from the New York Times website not long after it appeared there—it never made it into print, of course. This is why BBC radio in London immediately cut short their interview with me the second I replied that no, we were not banned because it offended the king. I’d done other, formally set up interviews with the BBC, TV and radio, before. Normally it’s set up in their local office. BBC radio in London must’ve seen the wire story and decided to do the story themselves, so this was not set up in their office. I could hear the interviewer’s surprise at my answer and the sudden ending of the interview, as if someone came in and instantly shut it down.

Macbeth’s relevance to contemporary Thai society is almost literal: a man of insatiable greed for power who sets himself up as an enemy to the king. That’s why it had to be a faithful adaptation, an extreme close-reading even, of Shakespeare. The usual cinematic solution of Macbeth as a gangster, say, would be a coy distraction. It has to be political for these words to make sense: “Alas poor country, almost afraid to know itself. It cannot be called our mother but our grave…” Ross’ lament is the reason I made ‘Shakespeare Must Die’. It’s even our theme song.

As for my depiction of Thai monarchy, filmmakers have mostly avoided it. This is because the visible and invisible rules are so unpredictable and the law is often used to discriminate against opponents. This means avoiding political and historical stories. That vast store is off-limit to us, incredible as it may seem.

10. Who has seen Shakespeare Must Die? Censor Must Die? (art galleries, international viewings, etc. I’ve seen that the Asian Shakespeare Association, for example, will screen the film at its conference)

Much of this I’ll answer along with question 11.

It’s funny to think now that while we were making the film, the people we feared most were not the censors but Shakespeareans, since I’m no Shakespearean scholar but an art school drop-out making a horror movie. As it turns out, most of the moral support we’ve received has come from Shakespeareans. Apart from local Shakespeareans, Professor Mark Burnette of the University of Belfast and the Indian director Rustom Bharucha have seen the film and given us wonderful feedback. Rustom Bharucha will hold a talk with me after the Asian Shakespeare conference screening. This should go ahead unless they too are deluged by emails from Thai Studies types, warning them not to show an anti-democratic evil elite propaganda film…(see below)

11. Are there possibilities of the film(s) being screened at international film festivals (such as Cannes, the Toronto International Film festival, etc.)?

No, there is absolutely no possibility of ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ being shown at Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Berlin etc. None, and not because it’s a crappy movie. I stand by this comment absolutely.

All, and I mean all, Asian cinema presented at the world’s great film festivals are controlled by the same small group of curators. They send scouts to our third world countries on film selection trips. (Such scouts even tell people how to cut their films. If you don’t obey the dictates of their tastes, you do not ‘go international’. That is why East Asian films shown at festivals are of the same type. This wouldn’t be so bad if local critics, colonially-shackled and lacking confidence, didn’t take their cue from these festivals. Thus entire national cinematic cultures are sacrificed at the altar of the festival circuit. I refuse to do this, so I do have this monolith against me as well as the Thaksin machine. If I had made my witches screechy ‘lady boys’, a Thai cliché, life might’ve been easier.)

The Cannes scout did come to my editing room. He said: “The politics are too specific.” He also “hated” my M and Lady M. Also, why make such a faithful Shakespeare adaptation, how unimaginative of me, how can I hope to compete with “real Shakespearean actors like Judy Dench etc.” as if we the savages have no right to ‘do’ Shakespeare unless we exoticise it, local colour being our only conceivable and acceptable contribution to Shakespearean cinema.

After we were banned, a French sales rep with Cannes connections asked for a DVD; he was initially ecstatic about the film and its chance of getting in at the last minute. Then silence. It was definitely shown to the selection committee. They would’ve consulted the scout in any case.

The Venice scout adored the film in the editing room, said it should be in competition blah blah, told me to rush the film’s completion for him, then at the last moment sends an email that it was not good enough to show to the selection committee, even saying that “the subtitles are in such weird, old-fashioned English”. The subtitles are of course the original text, “the work of one William Shakespeare”, as I put it to him.

Berlin, which had shown our ‘Citizen Juling’ not long before, said ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ “does not fit into our theme”—if we hadn’t been rejected, ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ would’ve been in Berlin the same year ‘Caesar Must Die’ won the Golden Bear.

Toronto asked for a DVD, then silence. None of which surprised me as the aforementioned Cannes film scout is also consulted by Berlin and Toronto, both of which that year, last year, showed just one Thai film, the same film, ‘Headshot’, a gunman movie incidentally co-produced by the very same film scout (and also funded by the Creative Thailand Film Fund, 8 million).

The very recent case of ‘Boundary’, a documentary described by many as sympathetic to Thaksin as it tells essentially the same version of events as Thaksin’s sister’s government, illustrates my point succinctly. It was the only Thai film at this year’s Berlinale. It was co-produced by Thai Palme d’Or winner Aphichartpong Weerasethakul and the same Cannes film scout (though he’s credited only as a Thank You) and funded by numerous Western film funds whose logos appear on film. After its Berlinale premiere, it was submitted to censors. What happens next says it all.

‘Boundary’ was at first banned by a censors’ committee headed by the most senior bureaucrat (non-politician) in the Ministry of Culture who accused it of distortion—a serious charge for a documentary. Unlike with ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ which was just vaguely charged of being a threat to national security, for the ‘Boundary’ ban the censors had a proper long list of their objections, minute by minute. (I haven’t seen it and can’t give my opinion, though I don’t believe in the banning of any film. People whose opinion I respect have gone so far as to describe it as a ‘red shirt film’ and ‘hate-speech’. I’m sorry to say I was invited to the local premiere but didn’t go. I’m too angry with this government to expose myself to unnecessary aggravation.)

Even so, in no time (just over 24 hours) the ban on ‘Boundary’ was suddenly lifted. This is legally impossible. Normally you have to file an appeal to the Film Board to reverse a ban; you have to do this within 15 days then the Film Board takes another 30 days to decide. These people hadn’t even filed an appeal. The censors actually phoned the director to “apologise for the misunderstanding”. The film then received an 18 rating (for those 18 and older), which is not even the highest rating (20), which the appeal committee told us to expect for ‘Shakespeare Must Die’ (and which we didn’t get, receiving instead an 18 to 4 vote to uphold the censors’ ban, along with additional charges of being a disgrace to good public morality and national dignity). To save face, the censors told them to mute some harmless sound from a scene of a celebration for the king’s birthday, so that it appears to have been banned for less than 2 days in order not to offend the king.

The ‘Boundary’ ban reversal is a great embarrassment for many. For us it’s a boon as we’ve been able to use it, as further irrefutable evidence of discrimination and political interference, to bolster our administrative court case. Also, we’ll be able to cite it if they do decide to ban our utterly truthful and factual documentary, ‘Censor Must Die’.

When ‘Citizen Juling’ was taken in hand by the same powerful film scout and invited to both Toronto and Berlin, he told me that when the title appeared on Toronto’s list of films in its official announcement, the festival was “deluged” with emails from Thai Studies academics, American professors at US universities whom he would not name, telling them to scrap ‘Citizen Juling’ from the programme—“You cannot show such an anti-democratic film” is one example as quoted by the film scout. Yes, the word used was not ‘undemocratic’ but ‘anti-democratic’, as in anti-Christ. “But the festival has decided to stand by your film,” was his conclusion then.

I have no proof that festivals received similar emails about ‘Shakespeare Must Die’, but given the film’s far-higher profile and Thai politics’ further infernal descent since then, as well as the merry go round of ecstatic-then-silent reactions, it’s not unreasonable to assume that they did. I do have an actual eye-witness to one incident: the director of a prominent contemporary art museum “furiously” told a film festival at that venue to remove the film from their list, “because we can’t upset another country’s government.” (I only happened to hear of it because the girl who was “screamed at in the middle of the museum office” is friends with an artist I know well.)

People aware of the situation did try to save us. In the end we screened at one festival in Seoul described as “middle-level but fiercely independent” called CinDi, where people sat around muttering stories about “the festival mafia”, even as members of that mafia appeared at the parties and at least one sat on the jury. CinDi was set up to fight the mafia, but now it no longer exists; that was the last edition. I’ve been told we got great press, but alas I can’t read Korean.

11. Last year, 37 plays in different languages from different countries came to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. The Guardian was running a feature asking directors and actors “Why Shakespeare is … French/German/South African, etc.?” So, I ask you “Why Shakespeare is … Thai…”

The fact that they banned our film shows how very Thai Shakespeare is.

Shakespeare transcends cultural differences because his focus is the universal human soul. He is especially relevant for Thai people because we are literally living through Shakespearean times.

12. In your public panel discussion on “Art and Censorship” (given at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand, 5 July 2012), the language that you use to describe Thai censorship and media control sounds very much like a dystopian novel: the popularity of mindless entertainment shows such as reality TV and game shows, the commercialization and politicization of dumbed down media, and, of course, the banning of difficult and intelligent films that may force viewers to think. Is Thailand heading into Orwellian territory here? What can be done to create smart, demanding, and problematic film and television options? Are there other filmmakers, directors, or artists that you feel are really pushing against this?

Of course we are in Orwellian territory. Bangkok has become the city with the highest number of facebook users in the world because under the Thaksin regime everything else is so heavily censored and spinned. But now Thai people can’t even speak freely on Facebook.

I’m not exaggerating. Thailand’s best loved political cartoonist, Chai Rachawat, an elderly man, is fighting a libel case, brought against him by Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, in criminal court, for a comment on his own facebook page. He was just letting off steam over a speech she made abroad with the line: “A prostitute sells only her body, but an evil woman sells out her whole country.” It’s not a cartoon in a newspaper, just a somewhat sexist personal comment to his facebook friends. He didn’t even name her. In another case this very week, the computer crimes police are interrogating four people including the senior political commentator at Thai PBS TV, for “spreading rumours of a coup d’etat” on his facebook page. He’d said that it was unlikely to happen.

Another example, a personal one. Last week at the last minute I was asked to be on a talk show at Thai PBS to defend the evil media against a family values media watchdog. It was obvious they couldn’t get anyone else to sit in the hot seat. The Family Foundation woman was upset with the dangerous behaviour of young people as portrayed by a cable TV series called ‘Hormones’, you know, kids taking drugs, sex and highly daring full frontal close-ups of bloody sanitary pads. (She was especially upset by that.)The damnedest thing that I should’ve been the one chosen to defend the very fortress that keeps me out. The director of the series, a famous film director, should’ve been the one to answer her, and I’m sure they tried but his producers must’ve told him not to feed the controversy. I haven’t even seen the series.

They did try but failed to get the president of the Thai Directors Association, Tanwarin Sukhapisit, whose film ‘Insects in the Backyard’ was banned for obscenity. She bravely fought the ban and was the first filmmaker to sue the censors in both the Administrative Court and the Constitution Court. (These courts did not exist when ‘My Teacher Eats Biscuits’ was banned.) She gave us the nerve to do the same, and stood by us as we went through the process. She used to be extremely outspoken, but she has since become very successful, making films for the biggest studio. This means she now has a lot to lose and has probably been told by studio handlers to downplay the warrior image. As directors’ guild president, she has vowed to continue campaigning for the end of the banning clause. (Our legal teams, along with Banjong Kosalawat, a distinguished director who has been fighting the banning clause for thirty years, have joined forces to propose a new film law.) Tanwarin lost her case at the Constitution Court (to interpret the banning clause as being unconstitutional), but her Administrative Court case, like ours, is still pending. We didn’t file with the Constitution Court—our more experienced human rights lawyer said it would hold everything up and be a waste of time.

Thai PBS ended up calling Manit Sriwanichpoom, my producer, who really couldn’t go. Normally he’s our spokesman, unless it’s in English. He told me I had to do it or no other filmmaker will defend our rights. In this climate of fear and rage, everyone’s afraid for their careers; I’m the only one with nothing left to lose but life and liberty. Manit is the one who’s actually had to face the censors and the film board in our fight to free ‘Shakespeare Must Die’, while I followed him around with a camera as a witness. He’s the star of ‘Censor Must Die’. But that day he really wasn’t free.

There was also a police psychologist and a media academic. The taping went fine. Except that when they aired it, they cut out everything I said about corruption (as in “Thai society’s concept of morality has been so distorted by fascist cultural engineering that we get upset by tops with spaghetti straps, though our quite recent ancestors wore even less; meanwhile a recent survey says 65% of Thais accept corruption so long as they personally benefit…We’re barking up the wrong tree.”), or anything else remotely connected with the Yingluck administration. This was a programme called ‘Thiang Hai Ru Ruang’ (“debate for clarity”), sponsored by a German foundation, to help to heal divisions in Thai society. So much for clarity.

I also said instead of fearfully banning evil, we should promote thought-provoking media and remove censorship so such media could flourish. Censorship is the very reason our media products are so bad; we’re prevented from touching real drama; our story-telling is so limited hence the prevalence of these slap-and-kiss fests that the Family Foundation is so concerned about. They cut that too. I said Tanwarin’s film is not porn as it was not made for sexual arousal; it’s a sad movie about love-starved people who try to fill their lives with sex and just get even sadder. You have to see the maker’s intent. They cut that too.

The show has an infantile gimmick: they tell “the opposing sides” to shake hands at the end. It was like a sitcom, so I hugged her instead. Ah, reconciliation achieved. I told you this long-winded story to show from my personal experience how out of fear even Thai PBS censors itself and collaborates with the spin.

Art and theatre have remained under their radar so far. Nevertheless, in a subtle way, Thaksin’s spindoctors are causing damage and distortion to Thai contemporary art. Now that every artist knows that the sure-fire way to ‘go international’ is to appear to criticise the monarchy or display some other marker of ‘controversy’, ‘democracy’ and ‘political integrity’, that is the way to go.

13. What would you be willing to do to make Shakespeare Must Die be released nationally? If the Censorship Board stated cut out this or that reference or allusion (e.g. the allusion to the 1976 Bangkok student uprising), what could/would you remove without harming the integrity of this film?

That decision is long past. The censors asked for “corrections”, which we refused to make. They objected to so many things: our use of red, Lady M’s jewellery, the lynching scene, on and on and on in a never-ending run-around.

From my contact with them, from their extreme reactions, I believe the thing that’s shaken them to the core is none of these things. Yes, they fear Thaksin, but they also fear William Shakespeare. They’d never seen or heard Shakespeare before, that’s all. This must seem incredible to you. But imagine that you’ve never experienced Shakespeare in any shape or form (except perhaps Zefferelli’s or Baz Luhrman’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’) and never in your own tongue, then suddenly you’re hit on the head with ‘Macbeth’ which, incredibly, is just like your own country. You’ve only ever heard straight-forward, predictable Thai dialogue, then suddenly you’re hit by Lady M, in Thai, but Shakespeare’s words, invoking evil spirits to enter her. Nothing in your life has prepared you for such an assault. It’s in verse but it’s totally natural, and oh so intense. Meanwhile the English subtitles appear, Shakespeare again, floating in and out like a moving Shakespearean graphic novel, emphasizing it still more that it’s the exact translation, no hanky-panky from me.

Perhaps because of our Buddhist background, Thai people tend to mistrust intensity; it’s just not good for your mental health. It’s obvious to me that it just blew their minds. They’d never heard words used like this before; the power and the intensity thrilled and terrified them. You can see this clearly in ‘Censor Must Die’. Manit is convinced that it doesn’t matter what we cut, they’d still feel threatened by it. The most-rewarding response I’ve ever received was from an economics professor after a screening at Chula University, who said he now understands why ‘farangs’ (white foreigners) enjoy Shakespeare. He could never see the point before.

For a non-Thai audience, I can easily remove the long talky ‘English scene’. I was tempted to remove it even before we shot it, since it’s extremely sensitive politically, hard to do well and potentially boring: talking heads, a man weeping, discussion on the divine right of kings. Uncinematic and risky in every way. Who wants to touch that? But its relevance for the Thai audience cannot be denied so I couldn’t cut it with a good conscience, out of sheer cowardice. For the Thai audience, I can remove nothing without harming the integrity and impact of the film. Other Thai films have portrayed October 14 and October 6 events. The censors’ objection is not the real one. We are being discriminated against. They only latched onto that scene because, horrors, it’s the October 6 massacre!!!

14. Is the Censorship Board missing all of the irony of banning your film, which is all about the banning of Shakespeare’s play?

They are too fearful to care about irony. Manit did point that out to them, but they didn’t care.

15. Finally, what is the current status of Censor Must Die? When will you hear more about Censorship Board’s decision?

The censors have been silent as the grave. They have until August 22nd (ten more days) to decide the fate of ‘Censors Must Die’, and may or may not summon us for questioning before they do. The ‘Boundary’ farce must tie their hands somewhat. It’s not going to be decided by them in any case. The current Minister of Culture is the husband of the then Minister of Culture (that’s how it works with the Thaksin regime), who looks none too good in the film. A summon is not a good sign, so there’s hope yet.