About This Clip

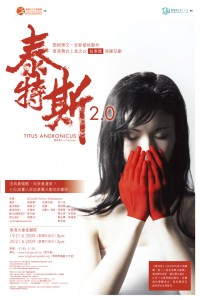

Titus 2.0

This minimalist 2009 adaptation of Shakespeare’s bloody and violent play Titus Andronicus is directed by Hong Kong theatre director Tang Shu-wing.

The Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio performed Titus 2.0 again in February 2011 at the Huayi – Chinese Festival of Arts held in Singapore.

For a recent study, see:

Howard Choy, “Toward a Poetic Minimalism of Violence: On Tang Shu-wing’s Titus Andronicus 2.0.” Asian Theatre Journal special issue edited by Alexander Huang, 28.1 (Spring 2011): 44-66.

Web: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/asian_theatre_journal/toc/atj.28.1.html

Redacted version: view essay

Titus 2.0

Clips

Interview: Dir. Tang Shu-wing

OurTV.HK interviews director Tang Shu-wing during rehearsal. Part 1 of 3

OurTV.HK interviews director Tang Shu-wing during rehearsal. Part 1 of 3 less

Interview: actress 黎玉清

OurTV.HK interviews an actress in the cast during rehearsal. Part 2 of 3

OurTV.HK interviews an actress in the cast during rehearsal. Part 2 of 3 less

Interview: actor 黃兆輝

OurTV.HK interviews an actor in the cast during rehearsal. Part 3 of 3

OurTV.HK interviews an actor in the cast during rehearsal. Part 3 of 3 less

Essays

Tang Shu-wing’s Titus Andronicus 2.0 and a Poetic Minimalism of Violence

Tang Shu-Wing’s approach in Titus Andronicus 2.0 (Hong Kong: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio, 2009) shows his rejection of sensationalist and consumerist presentations of the violence in the script.more

This extraordinary Hong Kong production of *Titus Andronicus* has been invited to the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival at the London Globe

Redacted from Howard Choy, “Toward a Poetic Minimalism of Violence: On Tang Shu-wing’s Titus Andronicus 2.0.” Asian Theatre Journal special issue edited by Alexa Huang, 28.1 (Spring 2011): 44-66.

(To watch the performance of Titus Andronicus 2.0 please click here.)

Tang Shu-Wing’s approach in Titus Andronicus 2.0 (Hong Kong: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio, 2009) shows his rejection of sensationalist and consumerist presentations of the violence in the script. Tang’s minimalism de-dramatizes violence via the narrative form of tale-telling, and then poeticizes it through the performance of the poetic body, creating a profound and thought-provoking production. Shakespeare’s most modern insight into the hellish darkness of humankind’s inhumanity is undoubtedly his invention of violence, be it expressed as war, vengeance, murder, rape, or any other form of cruelty and hatred. The questions left behind by the dramatist are: Which dramatic language is the most appropriate for presenting violence to today’s audience? Mimetic realism, stylized formalism, parodistic absurdism, or some other approach? Is violence actable? Are victims of violence representable? The issue is both ethical and aesthetical. And in the global context of geodramatics, between “Western” and “Eastern” productions, what kind of theatrical presentation can lead to an effective societal representation of violence? How can Asian theatre traditions enrich the exploration of the problematics of artistic (re)presentation of violence? Titus Andronicus, the most violent play attributed to Shakespeare, shows us how violence exercises its mighty power through human desires. It is a breathtaking thrill that has reemerged in recent decades to require us to rethink the present human condition in the world of violence. When the ancient Roman story was retold by Taiwanese, Japanese, and Hong Kong theatricians in the new millennium, Shakespeare was violently reinterpreted in Asia.

The first Hong Kong theatre artist to be bestowed l’Officier de l’ Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication in 2007, Tang Shu-wing strives to bring violence from a “subject of presentation” to a “subject of investigation.”2 Tang’s understanding of violence through Titus Andronicus, translated into Cantonese Chinese by Rupert Chan, was first showcased by his No Man’s Land (Wu ren didai, 1997-2009) for the 2008 Hong Kong Arts Festival.3 The cast of twelve actors all sat and performed side by side facing the audience before putting on their costumes at the end of the first act.4 Although the director employed no mise-en-scène and music (save an Indian raga in the opening, intermission, and ending), stage machinery and props were properly utilized. For example, in the end five empty chairs and a long dining table were beautifully presented with the furniture slowly moving counterclockwise from downstage center to upstage center following a semicircular orbit in the sitar music of “Raga Bilaskhani Todi” by Rash Behari Datta. Likewise effective was the staging as Aaron was hung up and brought down by wires (instead of being made to climb a ladder as directed in the Shakespearean text) during his trial, as the actors consistently shouted and roared throughout the five acts. Hong Kong theatre critic Cheung Ping-kuen (2008: 88) considers this rendition of Titus still a work of realism, which “provided little room for either actors or viewers to catch their breath and calm down. This made watching the play a rather hard-going and emotionally exhausting experience.” Other audience members, however, found the physical punishment of Aaron and Titus’ urge of Tamora to eat her son-pie rather amusing. Drama reviewer Leung Wai Sze (2009: 55) points out that the problem lies in Tang’s stylistic hesitation between the symbolic and the realistic. It reveals the predicament of representation.

Encouraged by his successful experiment of the actor-character transition in the first act of his 2008 production, Tang ventured to abandon the realistic representation of violence in his second attempt. Presented by the then renamed Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio, Titus Andronicus 2.0 is regarded as “the most important event in modern Hong Kong theatre aesthetics inof 2009” because of the significance of its nonrealistic narrativism in establishing “a new model for the theatre space, performing arts, as well as aesthetics” (Lo 2009: 14, 18), presented by the then renamed Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio, . Rfeatures a returning to both origins of Greek tragedy and Chinese storytelling,. Tang simply “tells us a story.” The script is rewritten into a story, that is, a narrative, in which the plotline and each character’s lines are assigned to various actors of a common chorus. By so doing, the characters are detached from any particular actor; they are “depersonalized.”5 The actors are not attached to any character, either; they are not representatives, but members of a chorus. The chorus, as proposed by the French acting theorist Jacques Lecoq (1921-99), frees a new space and creates a dimension transcending reality through human transmissions.6 Lecoq maintains that the chorus is the most essential element, the most beautiful, and the most moving dramatic experience in the space of tragedy. The tragic chorus raises the level of acting to masked performance by means of remote reactions to events:

In tragedy the role of the chorus is to warn, to give advice or sympathy; it is present throughout but never involves itself in the action…. In Greek tragedy battles are never shown; the chorus simply reacts to accounts of them. The great rule governing the tragic chorus is never to be active, always reactive. In the end, the chorus always displays wisdom. (Lecoq 2001: 131-132)

The wisdom is not derived from a militarized chorus, but from its players’ mental and physical improvisations; it arises between discipline and chaos, starting from a point of neutrality before an actor enters into the spirit of a character. With such wisdom, the violence of war is not understood from the perspective of any type of role, but from the standpoint of a pure human being.

Tang’s cast is in this production reduced from twelve actors to a chorus of seven for the twenty named roles.7 Like ancient Chinese storytellers, the performers simply sit on a row of chairs facing the audience and begin to tell the tale. Lecoq (103) has observed that in the Chinese tradition of storytelling “the telling of a tale is accompanied by the gestural evocation of images.” Storytellers explore and experiment with the internal dynamics of the text through their bodies, both vocally and physically. To demonstrate the importance of the gestural language, Lecoq borrows a differentiation between two linguistic terms, “speech” (le discours) and “the Word” (la parole): “Where ‘speech’ is stuck at the verbal level, ‘the Word’ involves the whole body.” And we listen to the individual words of the storytellers through their “poetic bodies” (corps poétique) (143). Their body movements are not mimetic, but poetic. Playing both the roles of a character and an observer, the storytellers provide us with their personal poetic visions and attitudes toward life. As Tang’s investigation further focuses on the actor’s body, the textual body is largely de-dramatized to a narrative.

The adaptation of the Bard’s script into a narrative is by Cancer Chong, who managed to radically revise the original by weeding out some superfluities from the plot.8 An actor, now posing as a storyteller, presents the main theme of the savage saga in the opening gambit: “This is a story of revenge” (Chong 2009: 1). The audience’s distance from the play’s first violent scene is doubled when the actor tells them, instead of acting out violence in front of them, that Tamora “amidst cheers and hails sees her own son being dismembered, his viscera being extracted and burned” (1). The diegesis distances the audience not only from the execution and sacrifice but also from the “cheers and hails.” The spectators are confronted with an uneasy awareness of the carnivalesque reaction to physical violence that they would have participated in inside the theatre, and by extension, in life to make entertainment out of naked violence. Chong takes the liberty of storytelling to describe the disgusting deliciousness of the cannibal cake that is beyond the audio-visual perceptions: “Saturninus and Tamora savor the food attentively. The freshly baked pies are so fleshy, juicy and tasty that the couple shower praises on Titus’ cooking skill” (26). Cheung Ping-kuen (2009a) suggests that narration can provide a distance to reduce and transcend the shock of violence on the one hand, but it may also induce and intensify the imagination of cruelty on the other. More importantly, violent behavior can be “aesthetically enriched” by the narrator’s interpretation, be it sympathetic or critical. Cheung sees the “aesthetic value” of violence as a motif in its cathartic or enlightenment effect on the part of the audience.

Before the story of Titus 2.0 begins, the auditorium resounds with the broadcast of current international and local news. Winnie Chau (2009: 93) has noted: “If this anachronistic prelude to the Elizabethan drama is an attempt to make a didactic connection between contemporary Hong Kong and Titus’s literally man-eat-man world, it is an understated one….” The didactic indeed gives way to the ritualistic when the actors take off their everyday clothes to reveal their plain black T-shirts and pants and ascend the stage in unison. Now on the bare stage with only seven chairs on it, the actors are sitting in line motionlessly and emotionlessly as they take turns, telling the story of the first act in a dim light. Not until the second act do they start to perform around their chairs and, when the spotlight enlarges, they move away from the chairs and gradually get inside the different characters temporarily as the story unfolds intermittently. The roles of Titus, Tamora, Aaron, Lavinia and others are not played by any particular actors, as everyone is a Titus, Tamora, Aaron or Lavinia and they are everyone. Everyone can represent them, because they are non-representable. In effect, the actors’ movements are largely non-representational, rather like non-narrative modern dance that conveys nothing more than a mood or motif. The overturned chairs between Acts II and III and the two tableaux of handstand on a chair between Acts IV and V, for example, demonstrate a world that is upside down. The choreography is a product of director-actor cooperation: Tang gave the guidelines to his actors, who constructed the movements; then he corrected and refined them.10

Besides body movements and meta-narrative gestures Tang uses verbal device and vocals of screaming, panting, chanting, and humming (e.g., om, aum, and houm) from the chorus to poeticize violence in his theatrical experiment. While Titus’ madness as a form of violence is performed in a polyphonic speech followed by a quick recitation, the violent abuse of Lavinia is indicated by hard and jerky breaths. Finally, in the last act, when the actors all sit back in their single-line chairs, facing the audience, and resume their identity as storytellers, the cruel climax appears so calm and low-key that the audience is freed from visual tension, so that their own imaginational and rational faculties can picture and judge the non-visualized violence as it is orally presented. Mainland Chinese drama critic Lin Kehuan (2009: 39) has said of the non-emotional experience of violence intended by Tang: “The calmness of the tone on stage and the violence in the story make a striking contrast.” Indeed, this contrast produces a dynamics of the story and the performance, though I cannot endorse Lin’s conclusion that Tang does not consider violence to be the point of investigation into human nature and social problems. The director desires to go beyond emotional catharsis for his investigation of violence.

Thus, the story and the performance are at once independent and interrelated, as the plot is constantly interrupted by pauses filled with body movements or vocal exercises. In their study of how narrativity gives explanatory power to the representation of violence, Berkeley scholars Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit pertinently point out that since violence is reduced to the level of a plot in a narrative framework, we have been conditioned to think of violence “as a certain type of eruption against a background of generally nonviolent human experience” (1985: 47). Bersani and Dutoit propose a tactic of de-dramatizing violence through denarrativization, for they equate narrativization with dramatization. In the theatre, however, diegetic narrativization is to de-dramatize mimetic representation. The problem of theatrical realism is, to borrow the words of Bate, “its representation of how ordinary human beings can be driven to extraordinary extremities of violence and cruelty” (1995: 66). As if violence were not part of human nature. Tang’s storytelling is to reveal violence without visualizing it. While maintaining the Shakespearean plot, the director further deconstructs the logic of violence by inserting frequent pauses of choreographic performance into the story.

The longest pause lasts six and a half minutes in Act V, Scene ii, before the climactic final scene of the play, when Titus commands his family to get ready for a “stern and bloody feast” (5.2.203; Chong 2009: 25). The three-minute stark silence followed by Nelson Hiu’s minimalist music is not merely a compelling pause before the zenith of retributive butchery, but also a quiet moment for the audience to ponder violence. Likewise, in lieu of the last couplet found in the 1594 first quarto edition of the Shakespearean script, “Then afterwards to order well the state, / That like euents may nere it ruinate” (Bate 1995: 277n), Cancer Chong creates an open ending with Lucius’ hesitation in making his decision on the fate of Aaron’s baby: “If I should raise this child, perhaps t’would serve as warning to the world?”11 The message, sent from a responsible adult Lucius instead of an “innocent” Young Lucius (as in the productions of Ninagawa, Howell, Taymor, and Wang), inserts doubt as to whether humanitarianism is the key to stop the vicious cycle of blood for blood. Tang leaves the question for us to answer by closing Titus 2.0 in a turning meditation performed by the actors.12 The spinning human bodies are clearly a humanistic echo to the rotating objects of five empty chairs and table at the end of his previous production of Titus haunting sitar accompaniment.

I would like to note that the improvisational live music created for Titus 2.0 by Nelson Hiu does not mimic the performance, but is a performance by itself.13 Often sounding like Japanese nô music, the Chinese vertical notch flute and two-stringed erhu-fiddle, mini Spanish cajón, all played by the composer himself, add melancholy to the cruel scenes and, more importantly, seek to create dialogues with the actors and their characters. More interesting than the traditional musical instruments are the found objects of plastic paper, glass goblets, metal bowls, tin cans, foil and chain appropriated by Hiu to create an eerily audible aura of violence at psychic moments, particularly during the second half of the prolonged pause before the cannibal climax as the sound effect resembles kitchen noises. Equally noteworthy is Leo Cheung’s lighting design that creates a special spatial sense of the simple stage set like a black box.14 With the all-black attire of the actors, the focused light design highlights the darkness of human violence rather than the purity of innocent victims as suggested by the above-mentioned Ninagawa production. Cheung’s use of red floodlight in the dark is more subtle and sublime than buckets of blood, and the torture of Aaron being radically reduced from the reliance on stage machinery in the first production to a touch of red light also reflects Tang’s minimalist approach in this second production.

Minimalism means understatement: less is more. Everything on the stage can be eliminated, except the actor’s body, which is regarded by Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874-1940) as the most essential element in theatre. Also impressed by Mei Lanfang’s stylized acting, Meyerhold’s acting theories have been developed in Polish stage director and theoretician Jerzy Grotowski’s (1933-99) idea of “poor theatre,” which stresses actors’ performance techniques rather than theatre technologies. Being a yoga trainer himself, Tang is a follower of both Meyerhold and Grotowski. In fact, Tang had a chance to participate in a workshop conducted by Grotowski while learning about Meyerhold through books and videos in France. His The Acting Theories of Meyerhold: Research and Reflection (Meiyehede biaoyan lilun: Yanjiu ji fansi, 2001) is the first systematic introduction of Meyerhold’s theories to Hong Kong readers.

Dubbed by Metropop magazine as an “alchemist of minimalist theatre,” Tang turns his studio into a laboratory, where he experiments with Meyerhold’s acting theories on the body. During the rehearsal of Titus 2.0, according to Larry Ng’s (2009: 2-4) observation, Tang instructed his actors to “use the five elements of breathing, humming, expression, movement, and action to tell the story,” calling their attention to the temporal length of each action as well as its “organic relations” with space and language. He urged them to minimize their actions, so as to maximize the expressions of their bodies. He repeatedly reminded them that their actions were mere forms to search for and stimulate the emotional impulse to release the energy from within their bodies. Tang’s training aims to activate his actors’ bodily energy in the form of physical improvisation. On top of action, narration demands a broader and deeper vision on the part of the actors. It requires them to step out of their roles and to transcend the time and space of both the story and reality. The development of Tang’s minimalist aesthetics with the act/art of storytelling opens up a space for his actors to explore their poetic bodies and examine their social existence.

Thus, for Tang (2004: 134), Meyerhold’s “biomechanics” is not merely an aesthetics of bodily balance and its ceaseless changes but also a “socio-mechanics” of ideological education. Tang insists: “For me minimalism is not only a form of aesthetic but also an attitude towards life” (2008: 17). Tang’s minimalism is sure to translate his anti-dramatization in the theatre house into anti-consumerism in everyday life. This explains why he loathes the “show biz” culture that has become very popular in post-colonial Hong Kong, post-capitalist Taiwan, and post-socialist China.15 Take for example the representation of rape as both a spectacle of violence and an exhibition of eroticism: how could we save the consumption of the actress as object of sexual desire from the collective gaze of the audience who, as Jean I. Marsden (1996: 186) notices in Ravenscroft’s Titus Andronicus, or the Rape of Lavinia, “Like the rapist, ‘enjoys’ the actress, deriving its pleasure from the physical presence of the female body”? As a minimalist, Tang provides no such visual markers as Ravenscroft’s (3.1.341) direction of Lavinia: “Loose hair, and Garments disorder’d, as ravisht.” Refusing to visualize violence into voyeurism, the Hong Kong director renders the victim’s “bodily presence” into a bodily poetics instead.16

Where mimetic realism draws on extreme visual violence to shock and please the public, poetic minimalism withdraws from cheap commercial tastes to discomfort and challenge the consumers. In the contemporary age of commercial reproduction, Tang’s poor theatre first de-dramatizes violence via the narrative form of tale-telling, and then poeticizes it through the performance of the poetic body. Such poetics seeks to double aesthetic distance, to minimize the representation of violence rather than to visualize the brutalities of life—not even a visual stylization. The “non-spectacularity” (bukeguanxing) of Tang’s presentation of violence (Tang C. 2009: 17), however, has developed a poetic aesthetics transcending moral terms. A profound and thought-provoking production, Titus 2.0 provides the Shakespearean tragedy with an alternative directorial choice between the Eastern and Western theatrical traditions by reinventing the ancient art of storytelling.

NOTES

1. Between 1930 and 2001 in China, for our concern, Titus was presented only once at Shanghai Theatre Academy’s first Shakespeare Festival in 1986, compared to twelve major productions of Romeo and Juliet, another apprentice tragedy by Shakespeare, and eight stage productions of each of King Lear and Macbeth (Li 2003: 233-240).

2. Tang’s remarks at a discussion organized by the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong) on 9 July 2009 (see Chan 2009: 22).

3. Rupert Chan is a veteran translator and playwright in Hong Kong. He has translated more than thirty drama scripts into Cantonese, including Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

4. All but one of the twelve actors working in this production received training from the School of Drama at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (hkapa), where both the director Tang Shu-wing and the leading actor Andy Ng (Titus) have been teaching. Cheung (2009b: 42) observes that the hkapa has provided Tang with a very important venue to further develop and practice his training methods in a steady teacher-student relationship. Ng, known for his specialty in movement, joined No Man’s Land after studying theatre at Middlesex University in London and the Practice Performing Arts School in Singapore.

5. The word is borrowed from Damian Cheng’s comments in the International Association of Theatre Critics discussion with Tang but not transcribed in Chan 2009.

6. Lecoq 2001: 127. Tang is indirectly influenced by Lecoq as he knows some of his students and has sat in their class presentations in Paris, where he studied acting at l’Ecole de la Belle de Mai and theatre studies at the Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle in the late 1980s.

7. Lecoq (2001: 131) suggests that seven is an ideal number with a chorus leader (coryphée) flanked by two half-choruses of three each; fifteen can also yield a marvelous dynamic. Only three actors (Andy Ng, Lai Yuk-ching, and Chu Pak-hong) from the previous production remain in this version; the other four newly recruited are also graduates of the hkapa with their major in acting.

8. A graduate of the School of Drama at the hkapa, Cancer Chong gained her M.A. in Theatre from the Royal Holloway College, University of London, and was a resident playwright of Chung Ying Theatre Company in Hong Kong. All English translations of Chong’s script are mine.

9. Tang has directed three Brecht plays, namely, The Wedding of the Petits Bourgeois (Paris: Théâtre de la Main d’Or, 1991), The Days of the Commune (Hong Kong: Besterben Drama Association, 1993), and The Exception and the Rule (Hong Kong: hkapa, 2008).

10. This is confirmed by Tang in our electronic correspondence dated 21 Dec. 2009 and reconfirmed by Lai Yuk-ching during my interview with her on 6 Aug. 2010 in Hong Kong. Tang worked as the choreographer in the creation of Les Chevaux aux Sabots de Feu for Théâtre du Bout du Monde as early as 1991, when he was in Paris.

11. Chong 2009: 28. I am indebted to my colleague Mimi S. Dixon for translating this line into Elizabethan English.

12. Cheung (2009a) points out the “religious sentiments” (zongjiao qingcao) in Titus 2.0 by relating the humming and spinning to Hindu/Buddhist chanting and Sufi whirling, respectively. The British play of Rome is thereby imbued with Indian and Islamic inspirations.

13. A Chinese and Japanese descendant born in Honolulu, Hiu studied ethno-musicology at the University of Hawai’i before moving to Hong Kong, where he has collaborated extensively in theatre and dance. Tang works with him when he needs live music, for instance, in his production of Hamlet for the hkapa at the 2006 International Arts Carnival in Hong Kong.

14. A graduate and currently Senior Lecturer of Theatre Lighting at the hkapa, Leo Cheung earned his Master in Lighting from the Queensland University of Technology.

15. Tang S. 2008: 17. Lin Kehuan (2009: 39), unfortunately, misinterprets Tang’s criticism as compliment and sees his “anti-dramatic drama” as a kind of “showing.”

16. Bate (1995: 36) reflects on the problem of Lavinia’s “bodily presence” as a violent display of the female figure: “Her body is at the centre of the action, as images of the pierced and wounded body are central to the play’s language.” Although during my interview with Lai Yuk-ching on 6 Aug. 2010 she admitted that her supine position in Titus 2.0 had meant to hint at Lavinia’s being raped, Tang has overtly denied this as his design (see Chan 2009: 22).

REFERENCES

Bate, Jonathan, ed. 1995.

Titus Andronicus. London: Routledge.

Beauman, Sally. 1982.

The Royal Shakespeare Company: A History of Ten Decades. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bersani, Leo, and Ulysse Dutoit. 1985.

The Forms of Violence: Narrative in Assyrian Art and Modern Culture. New York: Schocken Books.

Bloom, Harold. 1998.

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books.

Brook, Peter. 1968.

The Empty Space. New York: Atheneum.

Chan Fai Kin, ed. 2009.

“Taitesi jinhualun: Zuotan Taitesi 2.0” (On the evolution of Titus Andronicus: An informal discussion of Titus Andronicus 2.0). artism (Oct.): 19-23.

Chau, Winnie. 2009.

“Straight to the Heart: The Art of Saying More with Less.” muse (July): 92-94.

Cheung Ping-kuen. 2008.

“Man Is Not a Symbol.” muse (April): 86-88.

_____. 2009a.

Review of Titus Andronicus 2.0. Theatre Borderless. 27 June http://www.theatreborderless.com/abchk/a/news.do?method=detail&id=52913c5f21edb30101221d10291b0003&mappingName=FORUM (listed under “Drama Reviews”). Accessed 25 July 2010.

________ et al. 2009b.

“Erlinglingba nian Xianggang xiju huigu taolunhui—Huiyi jilu (cuolu)” (2008 Hong Kong Drama Review Forum: Minutes [extracts]). In Xianggang xiju nianjian 2008 (Hong Kong Drama Yearbook 2008). Ed. Bernice Kwok Wai Chan. Hong Kong: International Association of Theatre Critics, 35-42.

Chiang Chia-hua. 2006.

“Shashibiya de Meimeimen de jutuan—Taitesi” (Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group: Titus Andronicus). Xuite. 13 March <http://blog.xuite.net/ringfan/drama/5513491>. Accessed 25 July 2010.

Chong, Cancer. 2009.

“Taitesi 2.0” (Computer printout with director’s handwritten marginal notes).

Dessen, Alan C. 1989.

Titus Andronicus. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Dunne, Christopher, dir. 1998.

Titus Andronicus. VHS. New Port Ritchey, FL: Joe Redner Film & Productions.

Howell, Jane, dir. 1985.

Titus Andronicus. 2 VHS’s. [London]: BBC-TV and Time-Life Television.

Johnson, Samuel. 1840.

The Works of Samuel Johnson, LL. D. 2 vols. New York: Alexander V. Blake.

Lecoq, Jacques. 2001 [1997].

The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre (Le corps poétique). Trans. David Bradby [in 2000]. New York: Routledge.

Lee, Vico. 2003.

“Serving up Shakespeare as You Like It.” The Taipei Times, 2 May. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2003/05/02/204383. Accessed 25 July 2010.

Leung Wai Sze Jass. 2009.

“Jianwu yu shede de Taitesi 2.0” (Gradual awakening and giving up: On Titus Andronicus 2.0). Wenhua xianchang (C for Culture), no. 15 (July): 54-55.

Li Ruru. 2003.

Shashibiya: Staging Shakespeare in China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Liang Shiqiu [1903-87], trans. 1996.

Shashibiya quanji (Complete works of William Shakespeare). 8 vols. Hailaer: Neimenggu wenhua chubanshe.

Lin Kehuan. 2009.

“Taitesi 2.0, yi chu fan xijuxing de xiju” (Titus Andronicus 2.0: An anti-dramatic drama). Shun po (Hong Kong Economic Journal), 15 July.

Lo Wai Luk. 2009.

“Cong jianyue zhuyi dao xushi zhuyi—lun Deng Shurong de juchang kongjian tansuo” (From minimalism to narrativism: On Tang Shu-wing’s exploration of the theatre space). Paper presented at Problems and Methods: An International Symposium on Contemporary Drama Studies, Hangzhou, Oct. 23-25.

Marsden, Jean I. 1996.

“Rape, Voyeurism, and the Restoration Stage.” In Broken Boundaries: Women and Feminism in Restoration Drama. Ed. Katherine M. Quinsey, 185-200. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Murray, Barbara A. 2001.

Restoration Shakespeare: Viewing the Voice. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Presses.

Ng, Larry. 2009.

“Huigui benyuan, huigui jiben—jianzheng juchang de dansheng shike” (Back to the origins, back to the elementary: Witnessing the birth moment of the theatre). In Taitesi 2.0 (program), 2-4. Hong Kong: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio.

Ninagawa Yukio, dir. 2006.

Ninagawa x Shakespeare. III. 3 DVDs. Vol. 2. Taitasu Andoronikasu (Titus Andronicus). [Tokyo]: Horipro.

Pizzello, Stephen. 2005.

“A Conversation with Julie Taymor.” American Cinematographer 81. 2 (Feb. 2002): 64-73. Rpt. in Theatre and Film: A Comparative Anthology. Ed. Robert Knopf. New Haven: Yale University Press, 292-300.

Ravenscroft, Edward. 2005.

Titus Andronicus, or the Rape of Lavinia [1687]. In Shakespeare Adaptations from the Restoration: Five Plays. Ed. Barbara A. Murray, 1-88. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Tang Ching Kin. 2009.

“‘Ren zhi huigui’: Taitesi yu Deng Shurong de yishu luxian” (“The return to human”: Titus Andronicus and Tang Shu-wing’s artistic approach). artism (Oct.): 13-18.

Tang Shu-wing. 2004.

“Meiyehede biaoyan lilun: Yanjiu ji fansi zhaiyao” (Abstract of The Acting Theories of Meyerhold: Research and Reflection) [2002]. In Hecheng meixue—Deng Shurong de juchang shijie (Aesthetic of Synthesis: Theatre Art of Tang Shu Wing). Ed. Bernice Kwok Wai Chan and Damian Cheng, 131-136. Hong Kong: International Association of Theatre Critics.

_____. 2008.

“Shashibiya yu Xianggang, zai yu wo” (Shakespeare, Hong Kong and I). Trans. Maggie Lee. In Taitesi (program), 15-17. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Arts Festival and No Man’s Land.

Taymor, Julie, dir. 2000.

Titus. Special edition. 2 DVDs. Beverly Hills: Twentieth Century Fox.

Lavinia (Lai Yuk-ching) in Tang Shu-wing’s Titus 2.0, 2009.

By courtesy of Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio, Hong Kong.

Seven storytellers in Titus 2.0.

By courtesy of Tsang Man-tung.

Ivy Pang’s handstand tableau in Titus 2.0.

By courtesy of Yankov Wong.

Related Productions

- Taitasu Andoronikasu (Titus Andronicus) (Ninagawa, Yukio; 2006)

- Titus (Taymor, Julie; 1999)

- Titus Andronicus (Wang, Chia-ming; 2003)

- Titus Andronicus (1992) (Purcarete, Silviu; 1992)