Opening sequence: A self absorbed Lear (r)

Opening sequence: A self absorbed Lear (r)

Lear to his daughters (00:00:31)

Lear to his daughters (00:00:31)

Flattering Goneril (00:00:50)

Flattering Goneril (00:00:50)

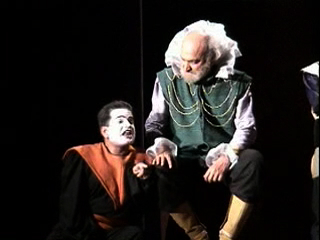

Cunning Regan (00:00:22)

Cunning Regan (00:00:22)

Cordelia’s dilemma (00:00:10)

Cordelia’s dilemma (00:00:10)

Lear perplexed (00:00:10)

Lear perplexed (00:00:10)

Cordelia’s plain speaking (00:00:46)

Cordelia’s plain speaking (00:00:46)

Lear’s fury (00:00:08)

Lear’s fury (00:00:08)

Ready to strike Kent (00:00:05)

Ready to strike Kent (00:00:05)

France’s proposal to Cordelia (00:00:39)

France’s proposal to Cordelia (00:00:39)

Edmund’s soliloquy (00:00:53)

Edmund’s soliloquy (00:00:53)

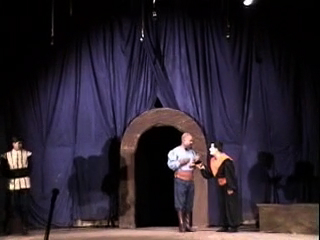

Kent in disguise (00:00:11)

Kent in disguise (00:00:11)

Lear takes umbrage at Oswald (00:00:08)

Lear takes umbrage at Oswald (00:00:08)

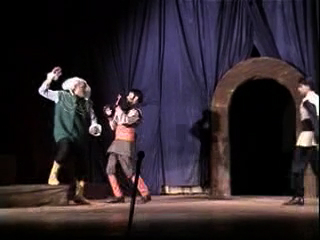

The witty Fool (00:00:42)

The witty Fool (00:00:42)

The wise and bitter Fool (00:00:30)

The wise and bitter Fool (00:00:30)

Lear’s curse (00:00:33)

Lear’s curse (00:00:33)

Artful Regan (00:00:32)

Artful Regan (00:00:32)

The sisters’s solidarity (00:00:18)

The sisters’s solidarity (00:00:18)

Regan pushes her luck (00:00:10)

Regan pushes her luck (00:00:10)

Ultimate betrayal (00:01:13)

Ultimate betrayal (00:01:13)

Lear’s storm of rage (00:01:13)

Lear’s storm of rage (00:01:13)

Remembers the Fool (00:00:41)

Remembers the Fool (00:00:41)

Lear’s self-realization (00:00:45)

Lear’s self-realization (00:00:45)

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard (00:00:14)

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard (00:00:14)

Blinding of Gloucester (00:00:07)

Blinding of Gloucester (00:00:07)

Monstrous Regan (00:00:15)

Monstrous Regan (00:00:15)

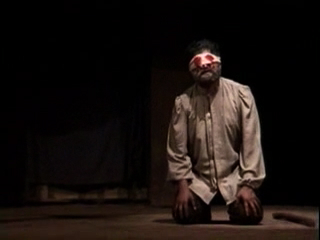

Gloucester in darkness (00:00:09)

Gloucester in darkness (00:00:09)

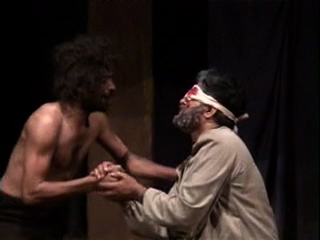

Gloucester begs Poor Tom to take him to Dover (00:00:45)

Gloucester begs Poor Tom to take him to Dover (00:00:45)

Goneril is attracted to Edmund (00:01:10)

Goneril is attracted to Edmund (00:01:10)

Goneril’s increasing power lust (00:00:27)

Goneril’s increasing power lust (00:00:27)

Gloucester’s suicide (00:00:22)

Gloucester’s suicide (00:00:22)

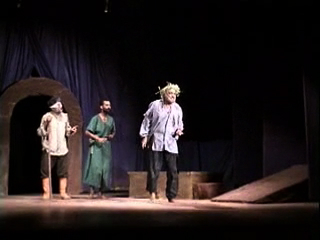

Mad Lear (00:00:33)

Mad Lear (00:00:33)

Both clarity and passion in madness (00:01:05)

Both clarity and passion in madness (00:01:05)

Reason in madness (00:01:20)

Reason in madness (00:01:20)

Self-realization through madness (00:00:41)

Self-realization through madness (00:00:41)

Cordelia “redeems nature” (00:01:28)

Cordelia “redeems nature” (00:01:28)

Lear is reborn (00:00:31)

Lear is reborn (00:00:31)

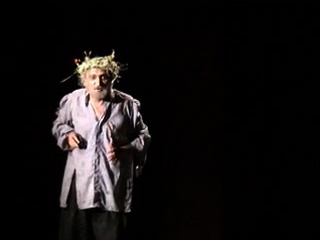

Edmund the Machiavel (00:00:25)

Edmund the Machiavel (00:00:25)

Lear welcomes his fate (imprisonment) (00:02:15)

Lear welcomes his fate (imprisonment) (00:02:15)

Lear with Cordelia in his arms (00:01:09)

Lear with Cordelia in his arms (00:01:09)

Lear imagines Cordelia speaks (00:00:41)

Lear imagines Cordelia speaks (00:00:41)

Lear’s final soliloquy (00:00:47)

Lear’s final soliloquy (00:00:47)

Edgar’s epitaph (00:00:35)

Edgar’s epitaph (00:00:35)

About This Clip

Raja Lear

Raja Lear, a 1993 Marathi-language adaptation of King Lear. Directed by Sharad Bhuthiadia from a translation by Vinda Karandikar.

A faithful translation, this production was performed in a manner ‘faithful’ to the tradition of realist staging of Shakespeare. This has been the most common staging practice for Shakespeare in India. Based on universalist assumptions of a stable and authoritative text, it performs Shakespeare straight letting the text speak for itself. It seeks to let the past live in the present, playing up its foreignness. Though sometimes critiqued as “derivative” and “essentialising,” this universalist staging practice, particularly in our colonial and postcolonial context, functions as an empowering mimicry. “Doing it like them” becomes a mastering of the master colonising text.

Further, the group, Pratyaya, coming from a provincial town like Kolhapur, is able to eschew the market rules of Bombay theatre: “Ours is a focused outlook on theatre,” says Sharad Bhuthadia, asserting that they choose to do meaningful theatre which can “go beyond and handle genuine human problems by going deep into the understanding of man’s life” (quoted in a review, Independent Journal of Politics and Business, 20 August 1993). Bhuthadia’s Raja Lear thus did not need any further entry points into the play, and while it performed an edited version, in three acts, it nevertheless, did full justice to the main themes of the play.

Its singular achievement was a deeply felt and internalized performance, not always easy for Shakespeare in translation; it received universal praise: “A high-powered fidelity to a Shakespearean text…. Never before had Marathi sounded so good on stage. Raja Lear was not just believable, it was real,” said R Ramanathan in the Independent Journal, while the Indian Express (20 August 1993) titled it a “Class Act.”

So successful was the universalizing of this production that critics had no difficulty in contemporising the play: “Lear becomes the tragedy of the India we are living in – the tragedy of a great nation being torn apart by centrifugal forces: of a political class composed of an imbecile king surrounded by sycophants (Regan and Goneril) and ruthless manipulators (Edmund); of the voices of sanity being disowned (Cordelia) and banished (Kent) or simply disappearing (Fool); of goodness having to pretend insanity (Edgar). Lear, then, does not remain the tragedy of one man. It becomes the tragedy of an entire people, an epoch.” (Sudhanva Deshpande, The Times of India, January 1993).

by Poonam Trivedi

Read more about the “universalized Shakespeare” performance style.

Video of performance took place on 26 Feb. 2001 at the Nataka Bharathi 2001 Shakespeare on Indian Stage, national theatre festival and seminar at Kasargode, Kerala, India, 24 Feb – 2 March 2001, in association with the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi. The role of Lear is played by Sharad Bhuthadia.

Raja Lear Clips and Images in this Collection

Act 1

- Opening sequence: A self absorbed Lear

- Lear to his daughters

- Flattering Goneril

- Cunning Regan

- Cordelia’s dilemma

- Lear perplexed

- Cordelia’s plain speaking

- Lear’s fury

- Giving away the crown (still)

- Ready to strike Kent

- Kent’s banishment (still)

- France’s proposal to Cordelia

- Cordelia’s leave taking (still)

- Edmund’s soliloquy

- Edmund resolves to act (still)

- Edmund and Edgar: villainy initiated (still)

- Goneril’s complaint (still)

- Kent in disguise

- Lear takes umbrage at Oswald

- The witty Fool

- The wise and bitter Fool

- Goneril confronts Lear (still)

- Lear’s curse

Act 2

- Gloucester pursuing Edgar (still)

- Artful Regan

- The sisters’s solidarity

- Regan pushes her luck

- Ultimate betrayal

Act 3

- Lear’s storm of rage

- Rage turns to self-pity (still)

- Remembers the Fool

- Edgar as Poor Tom (still)

- Lear’s self-realization

- Lear’s stormy education (still)

- Philosopher’ Tom (still)

- Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard

- Blinding of Gloucester

- Monstrous Regan

- Gloucester in darkness

Act 4

- Gloucester begs Poor Tom to take him to Dover

- Goneril is attracted to Edmund

- Goneril mocks Albany (still)

- Goneril’s increasing power lust

- Gloucester’s suicide

- Mad Lear

- Both clarity and passion in madness

- Reason in madness

- Self-realization through madness

- Cordelia “redeems nature”

- Lear is reborn

- Wisdom dawns (still)

- Final humility (still)

Act 5

- Edmund the Machiavel

- Lear welcomes his fate (imprisonment)

- Regan and Goneril squabble over Edmund (still)

- Edgar’s moral vengeance (still)

- Lear with Cordelia in his arms

- Lear imagines Cordelia speaks

- Lear’s final soliloquy

- Edgar’s epitaph

Raja Lear

Clips

Edgar’s epitaph

Edg: The weight of this sad time we must obey, Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say. The oldest have borne most; we that are young Shall...more

Edg: The weight of this sad time we must obey,

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest have borne most; we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.

[Exeunt, with a dead march]. (V.iii.323 – 326)

The contrasted lighting gave the end the effect of a tableau, signaling an iconic emblematisation of a pieta-like suffering (but with the genders reversed). The last lines given by Edgar, not Albany, spoken out to the audience formed an epitaph, a tribute to the story “the oldest hath borne most” … The production remained consistent in its use of a universalized western mise en scene throughout. less

Cunning Regan

Reg: I am made of the self same metal as my sister, And prize me at her worth. In my true heart I find she names my very deed of...more

Reg: I am made of the self same metal as my sister,

And prize me at her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love;

Only she comes too short; that I profess

Myself an enemy to all other joys

Which the most precious square of sense possesses,

And find I am alone felicitate

In your dear highness’ love. (1.i.69 – 76)

Lear: To thee and thine, hereditary ever,

Remain this ample third of our fair kingdom. (1.i.79 – 80)

Regan is more artful, makes larger hand gestures, bows, and is more than pleased with her reward, barely able to conceal her excitement in turning towards Cornwall. less

Cordelia’s dilemma

Cor: Nothing, my lord. (1.i.87) Cordelia, who had been standing at home distance, is positioned as different from the other two. Her “nothing” emerges out of an inner perplexity ,...more

Cor: Nothing, my lord. (1.i.87)

Cordelia, who had been standing at home distance, is positioned as different from the other two. Her “nothing” emerges out of an inner perplexity , a division between her duty to her own truth and that to her father. This Cordelia was the sweet, shy, sensible daughter, devoted to the father but unable to dissimulate like her sisters. There is a long stunned pause before her second “nothing.” less

Flattering Goneril

Gon: Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter; Dearer than eyesight, space and liberty; Beyond what can be valued rich or rare; No less than life,...more

Gon: Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter;

Dearer than eyesight, space and liberty;

Beyond what can be valued rich or rare;

No less than life, with grace health, beauty, honour;

As much as child e’er lov’d, or father found;

A love that makes breath poor and speech unable;

Beyond all manner of so much I love you. (1.i.54 – 61)

Goneril obliges, observes form, and bows. She is pleased with her gift as reward, and exchanges glances with Albany. less

Lear to his daughters

Lear: Give me the map there. Know that we have divided In three our kingdom; and ’tis out fast intent To shake all cares and business from our age Conferring...more

Lear: Give me the map there. Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom; and ’tis out fast intent

To shake all cares and business from our age

Conferring them on younger strenghts; while we

Unburden’d crawl toward death. Our son of Cornwall,

And you, our no less loving son of Albany,

We have this hour a constant will to publish

Our daughters’ several dowers, that future strife

May be prevented now. (1.i.37 – 44)

The division of the kingdom begins as genial gift giving with the patriarch expecting some ritual flattery in return. less

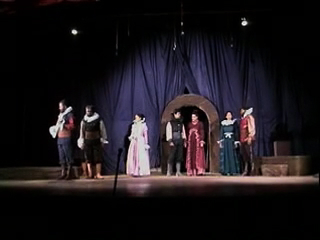

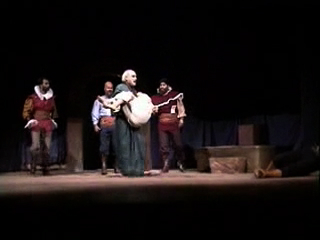

Opening sequence: A self absorbed Lear

Sennet. Enter King Lear, Cornwall, Albany, Goneril, Regan, Cordelia and Attendants. (1.i.) The play opened with Gloucester and Kent in conversation followed by the entry of the daughters with their...more

Sennet. Enter King Lear, Cornwall, Albany,

Goneril, Regan, Cordelia and Attendants. (1.i.)

The play opened with Gloucester and Kent in conversation followed by the entry of the daughters with their consorts and then Lear with his fool. What is noticeable is the immediate establishment of the Western ambience with quasi-Elizabethan costumes and Western music. Lear’s entry, though heralded by a fanfare, is of the self-absorbed monarch, who enters laughing form the side wing, not from the central ‘official’ door down stage from where the rest of the court enters. He has his arm around his Fool and is deep in conversation. He then strides up to his chair on the podium, releasing the Fool with a fond pat, but barely acknowledging those waiting for him. Bhuthadia’s staging saw this play as an individual tragedy, of an egocentric patriarch whose daughters fail to manage him. A comparison with the opening scenes of Samrat Lear 1 and Iruthiattam 4 will show the differences in the interpretation of the character and fare of Lear.

This universalizing stream of Shakespeare performance does not need spectacular stage effects. Its bare stage with minimal props could be any place and every place. The mood of the performance was thoughtful, with muted colors that blended well. less

Ready to strike Kent

Lear: O, vassal! Miscreant! (1.i.161) Challenged again, the monstrous ego of the monarch is ready to strike at Kent.more

Lear: O, vassal! Miscreant! (1.i.161)

Challenged again, the monstrous ego of the monarch is ready to strike at Kent. less

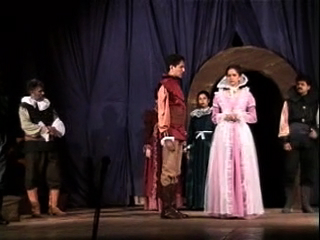

France’s proposal to Cordelia

France: Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich being poor; Most choice, forsaken; and move lov’d, despis’d! Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon; Be it lawful I take up...more

France: Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich being poor;

Most choice, forsaken; and move lov’d, despis’d!

Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon;

Be it lawful I take up what’s cast away.

Gods, gods! ’tis strange that from their cold’st neglect

My love should kindle to inflam’d respect. (1.i.250 – 255)

France takes up “what’s cast away” proposing in the classic western style by going down on his knees. For an indigenised version see Samrat Lear 9. less

Cordelia’s plain speaking

Cor: Good my lord, You have begot me, bred me, lov’d me; I Return those duties back as are right fit, Obey you, love you and most honour you. Why...more

Cor: Good my lord,

You have begot me, bred me, lov’d me; I

Return those duties back as are right fit,

Obey you, love you and most honour you.

Why have my sister’s husbands, if they say

They love you all? Happily, when I shall web

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty;

Sure I shall never marry like my sisters

To love my father all. (1.i.95 – 104)

Cordelia’s statement of her views, spoken out to the audience. Notice her poise and confidence and also her frown at her reference to her sisters’ professions of love. Contrast the more emotional Cordelia in Samrat Lear and the more controlled and determined one in Iruthiattam. less

Lear takes umbrage at Oswald

Lear: Do you bandy looks with me, you rascal? [Striking him.] Osw: I’ll not be stricken, my Lord. Kent: Nor tripp’d neither, you base foot-ball player. [Tripping up his heels.]...more

Lear: Do you bandy looks with me, you rascal? [Striking him.]

Osw: I’ll not be stricken, my Lord.

Kent: Nor tripp’d neither, you base foot-ball player.

[Tripping up his heels.]

Taking umbrage at his “faint neglect,” Lear ready to strike Oswald. Kent too adds his bit. less

Edmund’s soliloquy

Edm: Thou Nature, art my goddess; to thy law My services are bound. Wherefore should I Stand in the plague of custom, and permit The curiosity of nations deprive me,...more

Edm: Thou Nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom, and permit

The curiosity of nations deprive me,

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? Wherefore base? (1.ii.1 – 6)

The Subplot: Edmund discovered lying down, contemplating his fate; an angst-ridden villain who is aroused to question his fate, “Why bastard?” less

Kent in disguise

Kent: Now, banish’d Kent, If thou canst serve where thou dost stand condemn’d, So may it come, thy master, whom thou lov’st, Shall find thee full of labours. (1.iv.4 –...more

Kent: Now, banish’d Kent,

If thou canst serve where thou dost stand condemn’d,

So may it come, thy master, whom thou lov’st,

Shall find thee full of labours. (1.iv.4 – 7)

Kent in disguise, asserting his loyalty in a moment of spotlit introspection: “If thou canst server where thou dost stand condemn’d less

The sisters’s solidarity

Lear: O Regan! Will you take her by the hand? Gon: Why not by th’hand, sir? How have I offended All’s not offence that indiscretion finds And dotage terms so....more

Lear: O Regan! Will you take her by the hand?

Gon: Why not by th’hand, sir? How have I offended

All’s not offence that indiscretion finds

And dotage terms so. (II.iv.196 – 199)

The two sisters togethe embolden themselves to form a joint front against their father. less

The wise and bitter Fool

Fool: I have used it, Nuncle, e’er since thou mad’st thy daughters thy mothers; for whenz thou gave’st them the rod and putt’st down thine own breeches, Then they for...more

Fool: I have used it, Nuncle, e’er since thou

mad’st thy daughters thy mothers; for whenz

thou gave’st them the rod and putt’st down

thine own breeches, Then they for sudden

joy did weep, And I for sorrow sung, That

such a king should play bo-peep, And go

the fools among. (1.iv.179 – 185)

The Fool’s song becomes a bitter pill chastising the King for his folly. Lear looks more serious now. less

Lear’s curse

Lear: Hear, nature, hear! Dear Goddess, hear! Suspend they purpose, if thou didst intend To make this creature fruitful! Intro her womb convey sterility! Dry up in her the organs...more

Lear: Hear, nature, hear! Dear Goddess, hear!

Suspend they purpose, if thou didst intend

To make this creature fruitful!

Intro her womb convey sterility!

Dry up in her the organs of increase,

And from derogate body never spring

A babe to honour her! (1.iv.284 – 290)

The first sign of the unhinging of Lear’s mind by the extremity of his passion send in the curse of barrenness he wishes upon his own daughter, Goneril. The back lit figure of Lear, with other characters in darkness, emphasizes his isolation and shows the vehemence and the curse arising out of personal rejection and hurt. In Samrat Lear, the curse is irrational and avenging. less

The witty Fool

Fool: there, take my coxcomb. Why, this fellow has banish’d two on’s daughters, and did the third a blessing against his will: if thou follow him thou must needs wear...more

Fool: there, take my coxcomb. Why, this

fellow has banish’d two on’s

daughters, and did the third a blessing

against his will: if thou follow him thou

must needs wear my coxcomb. How

now, Nuncle! Would I had two

coxcombs and two daughters!

Lear: Why, my boy?

Fool: If I gave them all my living, I’d

keep my coxcombs myself. There’s

mine; beg another of thy daughters.

Lear: Take heed, sirrah; the whip. (1.iv.106 – 116)

The Fool was played as an archetypal courtly fool, but with the face painted as a white mask. He emerged in this production as both critic and sympathizer. Here the witty fool would gift his coxcomb, the symbol of the jester, to Kent and Lear who have already given away their wits. Note Lear’s initial indulgence towards him when he somewhat playfully reminds him of the whip. The word “boy” used by Lear for the Fool was translated as beta = son emphasizing the patriarch’s fondness for him. less

Remembers the Fool

Lear: My wits begin to turn. Come on, my boy. How dost, my boy? Art cold? I am cold myself. Where is this straw, my fellow? The art of our...more

Lear: My wits begin to turn.

Come on, my boy. How dost, my boy? Art cold?

I am cold myself. Where is this straw, my fellow?

The art of our necessities is strange,

And can make vile things precious. Come your hovel.

Poor Fool and knave, I have one part in my heart

That’s sorry yet for thee.

Fool: He that has and a little tiny wit,

With a hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

Must make a content with his fortunes fit,

Though the rain it raineth every day, (III.ii.67 – 77)

The buffeting by the storm clarifies and makes him see beyond himself and remember his Fool. This is juxtaposed with the Fool’s ironic message that one must make do with what one has, as Lear will now have to do. less

Regan pushes her luck

Reg: What need one? (II.iv.265) Regan pushes her luck, moving from “What should you need of more?”more

Reg: What need one? (II.iv.265)

Regan pushes her luck, moving from “What should you need of more?” less

Ultimate betrayal

Lear: No, you unnatural hags, I will have such revenges on you both That all the world shall — I will do such things, What they are, yet I know...more

Lear: No, you unnatural hags,

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall — I will do such things,

What they are, yet I know not, but they shall be

The terrors of the earth. You think I’ll weep;

No, I’ll not weep:

I have full cause of weeping, [Storm heard at a distance] but this heart

Shall break into a hundred though flaws

Or ere I’ll weep. O Fool! I shall go mad. (II.iv.280 – 290)

The ultimate betrayal: Lear tries to reason with himself but ends cursing his unkind daughters and on the edge of madness. less

Artful Regan

Reg: O, Sir! You are old; Nature in you stands on the very verge Of her confine: you should be ruled and led By some discretion that discards your state...more

Reg: O, Sir! You are old;

Nature in you stands on the very verge

Of her confine: you should be ruled and led

By some discretion that discards your state

Better than you yourself. Therefore I pray you

That to our sister you do make return; (II.iv.147 – 153)

Regan firmly, and with seeming reasonableness makes it clear that she will none of her father’s whims now. less

Gloucester begs Poor Tom to take him to Dover

Edgar: Bless thy sweet eyes, they bleed? Gloucester: Know’st thou the way to Dover? Edgar: Both stile and gate, horse-way and foot-path. Poor Tom hat been scar’d out of his...more

Edgar: Bless thy sweet eyes, they bleed?

Gloucester: Know’st thou the way to Dover?

Edgar: Both stile and gate, horse-way and

foot-path. Poor Tom hat been scar’d out of

his good wits: bless thee, good man’s son,

from the foul fiend! Five fiends have been in

Poor Tim at once; … So, bless thee master!

Glos: Here, take this purse, thou who the heav’ns’ plagues

Have humbled to all strokes: that I am wretched

Makes thee the happier: Heavens, deal so still! (IV.i.53 – 66)

The cruelty and pathos intensifies: blind Gloucester stumbles upon his runaway son Edgar. Like Lear blinded with anger, he too achieves insight being literally blinded. “Blessed thy sweet eyes, they bleed.” less

Monstrous Regan

Regan: Give me thy sword. A peasant stand up thus! [Takes a sword and runs at him behind] (III.vii.79) The production emphasized women’s lust for power and consequent emboldenment. Regan...more

Regan: Give me thy sword. A peasant stand up thus!

[Takes a sword and runs at him behind] (III.vii.79)

The production emphasized women’s lust for power and consequent emboldenment. Regan stabs the guard who revolts not once by twice, and then in departure from the text, herself injures Gloucester’s second eye. less

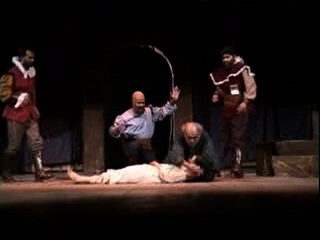

Blinding of Gloucester

Cornwall: See ‘t shalt thou never. Fellows hold the chair. Upon these eyes of thing I’ll set my foot. (III.vii.66 – 67) The blinding, realistic but not sensational. Cornwall’s back...more

Cornwall: See ‘t shalt thou never. Fellows hold the chair.

Upon these eyes of thing I’ll set my foot. (III.vii.66 – 67)

The blinding, realistic but not sensational. Cornwall’s back deflects the audience’s direct gaze. He uses his heels, not messing his hands, for this deed. less

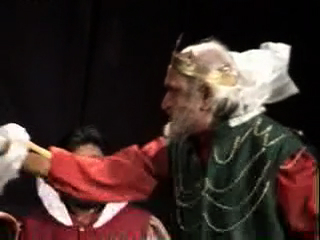

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard

[Regan plucks his beard]. Glou: By the kind Gods, ’tis most ignobly done To pluck me by the beard. Regan: So white, and such a traitor! (III.vii.35 – 37) The...more

Glou: By the kind Gods, ’tis most ignobly done

To pluck me by the beard.

Regan: So white, and such a traitor! (III.vii.35 – 37)

The blinding of Gloucester, in a realistic manner: Regan pulls at his beard in a rage but smiles to find some hair in her hand, and then flicks it off in disgust. It shows her growing sadism and arrogance. less

Lear’s self-realization

Lear: Poor nakes wretches, whereso’er you are, That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm, How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides, Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you...more

Lear: Poor nakes wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From season such as these? O! I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, Pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shakes the superflux to them,

And show the Heavens more just. (III.iv.28 – 36)

Lear’s ‘stormy education’ continues with a concretization of his realization that he has been too self absorbed in his kingship: “Poor nakes wretches less

Both clarity and passion in madness

Lear: Let copulation thrive: for Gloucester’s bastard son Was kinder to his father than my daughters Got ‘tween the lawful sheets. To’t, Luxury, pell-mell! For I lack soldiers. Behold yond...more

Lear: Let copulation thrive: for Gloucester’s bastard son

Was kinder to his father than my daughters

Got ‘tween the lawful sheets. To’t, Luxury, pell-mell!

For I lack soldiers. Behold yond simp’ring dame,

Whose face between her forks presages snow;

That minces virtue, and does shake the head

To hear of pleasure’s name;

The fitchew now the soiled horse goes to’t

With a more riotous appetite.

Down from the waist they are all Centaurs,

Though women all above:

But to the girdle do the god’s inherit,

Beneath is all the fiend’s: there’s hell, there’s darkness,

There is the sulphurous pit-burning, scalding,

Stench, consumption; fie, fie, fie! pah, pah!

Give me an ounce of civet, good

apothecary, To sweeten my imagination. (IV.vi.117 – 133)

Yet there is reason in his madness; he hits out at his tormentors, the legitimately begot daughters: “Let copulation thrive less

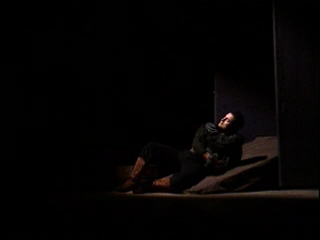

Gloucester’s suicide

Glou: Now, fellow, fare thee well. Edgar: Gone, sir: farewell. [He throws himself forward and fall] (IV.vi.41) Gloucester’s suicide where the ludicrous flop is redeemed only by the pathos of...more

Glou: Now, fellow, fare thee well.

Edgar: Gone, sir: farewell.

[He throws himself forward and fall] (IV.vi.41)

Gloucester’s suicide where the ludicrous flop is redeemed only by the pathos of the situation. Direct and effective staging without frills or stage business. less

Mad Lear

Lear: Look, look a mouse. Peace, peace! This pieve of toasted cheese will do’t. There’s my gauntlet; i’ll prove it on a giant. Bring up the brown bills. O! well...more

Lear: Look, look a mouse. Peace, peace!

This pieve of toasted cheese will do’t.

There’s my gauntlet; i’ll prove it on a giant.

Bring up the brown bills. O! well flown bird; i’

th’ clout, i’ th’ clout: hewgh! Give the word. (IV.vi.89 – 93)

Lear’s mad state “crown’d with rank fumiter and furrow-weeds less

Goneril’s increasing power lust

Gon: [Aside] One way I like this well; But being widow, and my Gloucester with her, May all the building in my fancy pluck Upon my hateful like: another way,...more

Gon: [Aside] One way I like this well;

But being widow, and my Gloucester with her,

May all the building in my fancy pluck

Upon my hateful like: another way,

The news is not so tart. (IV.ii.83 – 87)

Goneril’s soliloquy reveals her growing power lust: the news of Cornwall’s death brings no sense of grief for the bereaved sister but a quiet relish. Things may turn to her advantage. Note the front spotlight effect, same as in her brief soliloquy after giving Edmund the token, establishing a continuity of thought through stage effect. less

Goneril is attracted to Edmund

Goneril: Back, Edmund, to my brother; Hasten his musters and conduct his powers: I must change arms at home, and give the distaff Into my husband’s hands. This trusty servant...more

Goneril: Back, Edmund, to my brother;

Hasten his musters and conduct his powers:

I must change arms at home, and give the distaff

Into my husband’s hands. This trusty servant

Shall pass between us: ere long you are like to hear,

If you dare venture in your own behalf,

A mistress’s command. Wear this; spare speech; [Giving a favour]

Decline your head: this kiss, if it durst speak,

Would stretch thy spirits up into the aire.

Conceive, and fare thee well.

Edm: Yours in the ranks of death.

Gon: My most dear Gloucester! [Exit Edmund]

Oh! The difference of man and man.

To thee a woman’s services are due:

My fool usurps my body. (IV.ii.15 – 28)

Goneril’s ‘power-play.’ She gives a token to Edmund who responds to it kneeling down in a gesture from western chivalry. less

Gloucester in darkness

Cornwall: Lest it see more, prevent it. Out vile jelly! Where is thy lustre now? (III.vi.80 – 81) Darkness, symbolic not just of what has been done to Gloucester, but...more

Cornwall: Lest it see more, prevent it. Out vile jelly!

Where is thy lustre now? (III.vi.80 – 81)

Darkness, symbolic not just of what has been done to Gloucester, but of the pervasive blindness, floods the stage. less

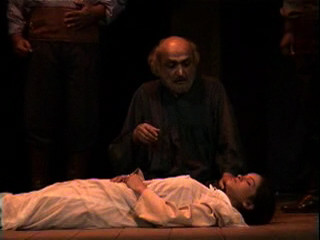

Lear with Cordelia in his arms

Re-enter Lear, with Cordelia dead in his arms; Officer. Lear: Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones: Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so...more

Re-enter Lear, with Cordelia dead in his arms; Officer.

Lear: Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones:

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone for ever.

I know when one is dead, and when one lives;

She’s dead as earth. Lend me a looking glass;

If that her breath will mist or stain the stone,

Why, then she lives. (V.iii.257 – 263)

Lear with the dead Cordelia in his arms comes in howling, puts her down front stage. He cannot believe that she is dead. less

Lear welcomes his fate (imprisonment)

Lear: No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison. We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage: When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down, And...more

Lear: No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison.

We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too-

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out-

And take upon ‘s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies; and we’ll wear out,

In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones

That ebb and flow by th’ moon.

Edm: Take them away.

Lear: Upon such sacrifices, my Cordelia,

The Gods themselves throw incense. Have I caught thee?

He that parts us shall bring a brand from heaven

And fire us hence like foxes. Wipe thine eyes.

The good years shall devour them, flesh and fell,

Ere they shall make us weep! We’ll see ’em starv’d first.

Com. [Exeunt Lear and Cordelia, guarded]. (V.iii.8 – 26)

Lear and Cordelia. The King and patriarch refuses to see his other daughters to beg for his freedom and welcomes prison where they two will “sing like birds i’ th’ cage less

Edmund the Machiavel

Edm: To both these sisters have I sworn my love; Each jealous of the other, as the stung Are of the adder. Which of them shall I take? Both? One?...more

Edm: To both these sisters have I sworn my love;

Each jealous of the other, as the stung

Are of the adder. Which of them shall I take?

Both? One? Or neither? Neither can be enjoy’d,

If both remain alive: to take the widow

Exasperates, makes made her sister Goneril;

And hardly shall I carry out my side,

Her husband being alive. Now then, we’ll use

His countenance for the battle, which being done,

Let her who would be rid of him devise

His speedy taking off. As for the mercy

Which he intends to Lear and to Cordelia-

The battle done, and they within our power,

Shall never see his pardon; for my state

Stands on me to defend, not to debate. (V.i.55 – 69)

Edmund, the machiavel, is recounting his deeds: “To both sisters have I sworn my love less

Lear is reborn

Cor: O, look upon me, Sir, And hold your hands in benediction o’er me. No, sir, you must not kneel. Lear: Pray, do not mock me. I am a very...more

Cor: O, look upon me, Sir,

And hold your hands in benediction o’er me.

No, sir, you must not kneel.

Lear: Pray, do not mock me.

I am a very foolish fond old man,

Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less;

And, to deal plainly,

I fear I am not in my perfect mind.

Methinks I should know you, and know this man;

Yet I am doubtful; for I am mainly ignorant

What place this is; and all the skill I have

Remembers not these garments; nor I know not

Where I didn lodge last night. Do not laugh at me;

For, as I am a man, I think this lady

To be my child Cordelia.

Cor: And so I am! I am! (IV.vi..57 – 70)

Lear is reborn, a new man. There is the humbling of the egotistical parent: instead of blessing Cordelia, as she wants, Lear kneels in embarrassment. There is confusion and slow recognition of himself and others. less

Cordelia “redeems nature”

Cor: And wast thou fain, poor father, To hovel thee with swine and rogues forlorn, In short and musty straw? Alack, alack! ‘Tis wonder that thy life and wits at...more

Cor: And wast thou fain, poor father,

To hovel thee with swine and rogues forlorn,

In short and musty straw? Alack, alack!

‘Tis wonder that thy life and wits at once

Had not concluded all. He wakes. Speak to him.

Doct: Madam, do you; ’tis fittest.

Cor: How does my royal Lord? How fares your Majesty?

Lear: You do me wrong to take out o’ th’ grave.

Thou art a soul in bliss; but I am bound

Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears

Do scald like molten lead. (IV.vii.38 – 48)

At last Cordelia’s care; she keeps vigil over her father, but as he wakes, she moves to respectful distance from his bed. Notice the contra jure lighting giving intimate, spotlight atmosphere, suggestive of the grouping in Renaissance painting. less

Self-realization through madness

Lear: When we are born, we cry that we are come To this great stage of fools. This’ a a good block. It were a delicate stratagem to shoe A...more

Lear: When we are born, we cry that we are come

To this great stage of fools. This’ a a good block.

It were a delicate stratagem to shoe

A troop of horse with felt. I’ll put’t in proof,

And when I have stol’n upone these sons-in-law,

Then kill, kill, kill, kill, kill, kill! (IV.vi.184 – 189)

His self-realization born of madness: “When we are born, we cry that we are come / To this great stage of fools.” less

Reason in madness

Lear: There thou might’st behold The great image of Authority: A dog’s obeyed in office. Thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody hand! Why dost thou lash that whore? Strip thine...more

Lear: There thou might’st behold

The great image of Authority:

A dog’s obeyed in office.

Thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody hand!

Why dost thou lash that whore? Strip thine own back:

Thou hotly lusts to use her in that kind

For which thou whipp’st her. The usurper hangs the cozener.

Thorough tatter’d clothes small vices do appear;

Robes and furr’d gowns hide all. Plate sin with gold,

And the strong lance of justice hurtles breaks;

Arm it in rages, a pigmy’s straw does pierce it.

None does offend, none, I say none; I’ll able ’em:

Take that of me, my friend, who have the power

To seal th’ accuser’s lips. (IV.vi.161 – 174)

There is insight in the madness too: “Handy-dandy, which is the justice, which is the thief? less

Lear perplexed

Lear: Nothing will come of nothing; speak again. (1.i.90) Lear, who had invited her speak in the first instance with a marked fondness in his tone, is now taken by...more

Lear: Nothing will come of nothing; speak again. (1.i.90)

Lear, who had invited her speak in the first instance with a marked fondness in his tone, is now taken by surprise; he strides down to her, to ask her, still mildly, to speak again. This Lear in contrast to Samrat Lear and Iruthiattam is more self-absorbed than egotistical; it is not his vanity but an inner being that is hurt. He is the most believable of the three. less

Lear’s storm of rage

Lear: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow! You cataracts and hurricanes, spout Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks! You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires, Vaunt-couriers of...more

Lear: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!

You cataracts and hurricanes, spout

Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks!

You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head! And thou, all shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world!

Crack Nature’s moulds, all germens spill at once

That makes ingrateful man! (III.ii.1 – 9)

The storm in nature is an emblem of the storm in Lear’s soul. The staging of the storm in ‘universalized Shakespeares’ is a symbolic realism, with just enough sound and light effects that stop short of a naturalistic spectacular impact. The fury of nature was signaled without recreating it. This focused attention on the convulsion overtaking Lear. In this production it as Lear’s singular alienation, which was given prominence and helped by the excision of the opening choric scene between Kent and a Gentleman. less

Lear imagines Cordelia speaks

Lear: A plague upon you, murderers, traitors all! I might have sav’d her; now she’s gone for ever! Cordelia, Cordelia! Stay a little. Ha! What is’t thou say’st, Her voice...more

Lear: A plague upon you, murderers, traitors all!

I might have sav’d her; now she’s gone for ever!

Cordelia, Cordelia! Stay a little. Ha!

What is’t thou say’st, Her voice was ever soft,

Gentle, and low, an excellent thing in woman.

I kill’d the slave that was a-hanging thee. (V.iii.269 – 274)

Lear is so disconsolate with grief, that he does not recognized Kent, instead almost rebukes him, as he tries to console him. He imagines he sees Cordelia’s lips move and tries to catch her voice. less

Lear’s final soliloquy

Lear: And my poor fool is hang’d! No, no, no life! Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life, And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come no...more

Lear: And my poor fool is hang’d! No, no, no life!

Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life,

And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come no more,

Never, never, never, never, never!

Pray you, undo this button. Thank you, Sir.

Do you see this? Look on her! her lips!

Look there, look there! [Dies] (V.iii.305 – 311)

Lear tries to rouse Cordelia, but realizes she is gone – picks up her hand which falls dead flat. But in his final breath again sees some signs of life in her: Look on her, look, her lips, less

Essays

Shakespeare in India: Modes of Performance

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional.more

- Universalized Shakespeare

- Localized Shakespeare

- Indigenised Shakespeare

- English Language Shakespeare

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional. These are artists who do not earn their main living in theatre, yet devote all their leisure and creative energy to it, run theatre groups and even travel with their shows to different parts of the country. Bhuthadia’s group, Pratyaya, chose to perform Lear inspired by the much acclaimed translation by Vinda Karnadikar, eminent Marathi poet, who is able to capture the nuances of Shakespeare’s language without sacrificing its images or allusions.

A faithful translation, it was performed in a manner ‘faithful’ to the tradition of realist staging of Shakespeare. This has been the most common staging practice for Shakespeare in India. Based on universalist assumptions of a stable and authoritative text, it performs Shakespeare straight letting the text speak for itself. It seeks to let the past live in the present, playing up its foreignness. Though sometimes critiqued as “derivative” and “essentialising,” this universalist staging practice, particularly in our colonial and postcolonial context, functions as an empowering mimicry. “Doing it like them” becomes a mastering of the master colonising text.

Further, the group, Pratyaya, coming from a provincial town like Kolhapur, is able to eschew the market rules of Bombay theatre: “Ours is a focused outlook on theatre,” says Sharad Bhuthadia, asserting that they choose to do meaningful theatre which can “go beyond and handle genuine human problems by going deep into the understanding of man’s life” (quoted in a review, Independent Journal of Politics and Business, 20 August 1993). Bhuthadia’s Raja Lear thus did not need any further entry points into the play, and while it performed an edited version, in three acts, it nevertheless, did full justice to the main themes of the play.

Its singular achievement was a deeply felt and internalized performance, not always easy for Shakespeare in translation; it received universal praise: “A high-powered fidelity to a Shakespearean text…. Never before had Marathi sounded so good on stage. Raja Lear was not just believable, it was real,” said R Ramanathan in the Independent Journal, while the Indian Express (20 August 1993) titled it a “Class Act.”

So successful was the universalizing of this production that critics had no difficulty in contemporising the play: “Lear becomes the tragedy of the India we are living in – the tragedy of a great nation being torn apart by centrifugal forces: of a political class composed of an imbecile king surrounded by sycophants (Regan and Goneril) and ruthless manipulators (Edmund); of the voices of sanity being disowned (Cordelia) and banished (Kent) or simply disappearing (Fool); of goodness having to pretend insanity (Edgar). Lear, then, does not remain the tragedy of one man. It becomes the tragedy of an entire people, an epoch.” (Sudhanva Deshpande, The Times of India, January 1993).

The localized Shakespeare is another performative style, particularly favoured in the earlier years, which imported a definite Indian flavour and colouring to transform the alien vastness of the text into an accessible familiarity. The degree of change varied: while the adaptations of the Parsi theatre in the 1880s took great liberties with Shakespeare’s plot, character and even words, the post- independence localizations have been attempts to root Shakespeare more acutely in a specific local ambience. The production, chosen to illustrate this stream of performance, is a student production of the National School of Drama. Samrat Lear, directed by John Russell Brown.

The National School of Drama, in New Delhi, has a tradition of inviting directors from different parts of the country and from abroad to train their students in a variety of performative styles. Visiting English directors have often chosen to direct Shakespeare even though the performances are always in a Hindi translation. John Russell Brown’s production played almost the full text – a marathon three and half hour long performance – in a translation by Harivansh Rai Bachchan, one of the foremost Hindi poets of the twentieth century. Brown’s own closeness and expertise with the English text gave the production sharply etched characterisation, robust energy, and a particular focus on the narrativisation of the story.

Its localization was not to resituate the story in another well-defined place or period, but to let its relocation emerge from the theatrical event in Delhi. “I have not localised the story in any specific way,” Brown said in an interview with the author, “because we were not doing an “authentic” Indian production. I wanted this Lear to speak beyond the moment.” To this end, he said, he had “encouraged the [student] actors to use their own ‘folk’ physicalities, (their own understandings of their theatre traditions) in their responses to s,” because he believed that a “play lives between the actor and the audience.” The result was a fairly successful attempt to meld the conventions of the traditional theatre, the style of the modern Indian theatre with the speech rhythms of Hindi onto the story of Shakespeare.

Traditional Indian costuming and music added the finishing touches. As Kavita Nagpal, seasoned theatre critic, remarked, the production made “the play breathe in a way that was both historical and contemporary” (Hindustan Times, 15 March 1997). Both these productions, the universalized Shakespeare, Raja Lear, and the localized Shakespeare, Samrat Lear, though divergent in their performative styles, shared a conventional interpretative stance. They ventured no innovative critical perspectives on the text, trusting a ‘straight’ telling of the tale. They both proved that Shakespeare in translation could successfully speak to its audiences.

The indigenised Shakespeare is perhaps the most creative and, therefore, somewhat controversial form of staging Shakespeare in India. Here, the Shakespeare text is not just adapted but appropriated and acculturated into an indigenous theatre form. Devotees of the literary text find this kind of transformation a desecration; yet successful indigenisations, which immerse Shakespeare’s text into another aesthetic and cultural worldview, can spark off new meanings and fresh configurations of the same text. The production chosen to illustrate this genre of performance is a rewritten version of Lear entitled Iruthiattam (The Final Game) directed by R. Raju from a Tamil translation and adaptation made by well-known novelist and playwright, Indira Parthasarathy and presented by the theatre group, Arangam. R. Raju, from the School of Performing Arts at Pondicherry University, and a former NSD graduate, belongs to the Kerala school of experimental theatre, the ‘nataka karali,’ making appropriation and adaptation his metier. And Arangam is no ordinary theatre group either; it consists of highly skilled artists – dancers, musicians and folk theater practitioners – in their own right. Together they created a tightly structured, economical production distinguished by consistency and unity of rasa or mood. It interprets the play in terms of a power struggle, retains part of the sub-plot to make a feminist point that sons too can be cruel, and ends with the storm scene at the end of which Cordelia appears to rescue Lear.

But its indigenisation derives more from its performative style, which adapts the conventions of the terukutoo, a popular street theatre folk form of Tamil Nadu, traditionally performed by the socially disadvantaged. The inherent subversivness and spontaneity of the terukutoo, centering on the improvisatory energy of the fool I komali, was the main interpolation into the text and this was specially manifested in the highlighting of a contrapuntal relationship between the fool and the king. The strong phyicalised style, acrobatic and earthy, with its vigorous song and dance routines, made Iruthiattam lively and entertaining, transforming King Lear from a reworked classic into a kind of a ‘people’s Shakespeare.’

Even though the adaptation was titled “The Final Game” it did not in the least subscribe to a Beckett-like doom and gloom of Endgame. Since this version took liberties to play around with and cut up Shakespeare’s canonical text to suit its own radicalising perspective, it may also be seen as an example of the postcolonial Shakespeare.

Apart from these, the English language Shakespeare is best represented by an amateur student production of King Lear by the St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, one of the oldest collegiate dramatic societies with an almost unbroken record of performing Shakespeare for over 75 years since 1924. Arjun Raina, a young actor director worked closely with the students drawing out their impressions and structuring them into stageble ideas. The production was marked by an iconoclastic irreverence, at times a plainly undergraduate-ish swipe at tradition, which nevertheless produced some novel stage images, e.g. the introduction of a whimsical Lear in boxer shorts and gloves brought onstage reclining in a brightly coloured coffin symbolizing the death of the monarch.

The rest of the cast sat on and moved around with high but crude wooden stools that wobbled and wavered at every step, imaging Lear’s world as full of social climbers caught in the instabilities of the social hierarchy. The characteristic opening sequence had all the court, clad in black and white, looking harlequinesque, streaming in to ‘view’ the show of Lear’s division of the spoils through tinseled masks and opera glasses (these were changed to dark glasses after the blinding of Gloucester) as also looking, observing, spying on each other – all heightened, perched on the wooden stools. Lear chased his screaming daughters down the stage and then pieces of cake were passed around during the division of the kingdom.

Though this production was peppered with more deconstructive sallies than it could ultimately pull through coherently, it was unusual in the liberties it took – informed by the iconoclasm of contemporary western staging practice – because the norm for the English language collegiate Shakespeare, performed for a pedagogic purpose, has been a traditional staging in period costume. less

Shakespeare in India: Chronology of King Lear Productions in India

1832 Scenes, Lear (III.iii), English, Chowringhee Theatre, Calcutta. 1880 Atipidacarita, Marathi, tr./adapt. S M Ranade, Aryodharak Company, Poona. 1897 Rajavu Lear, Malayalam, tr./dir./actor Govinda Pillai, Trivandrum. more

(Citing language, translator, director, group and place based on available information).

1832 Scenes, Lear (III.iii), English, Chowringhee Theatre, Calcutta.

1880 Atipidacarita, Marathi, tr./adapt. S M Ranade, Aryodharak Company, Poona.

1897 Rajavu Lear, Malayalam, tr./dir./actor Govinda Pillai, Trivandrum.

1906 Har Jeet, Urdu. Munshi Murad Ali, dir. David Joseph. Victoria Theatrical Company, Bombay.

1907 Safed Khoon, Urdu, Agha Hashr Kashmiri, Parsi Company, Bombay.

(1919) ” ” Jalal Ahmed Shah

1962 Lear, English, St Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society with Roshan Seth, Delhi.

1964 Raja Lear, Urdu, tr. Majnoon Gorakhpuri, dir. Ebrahim Alkazi, National School of Drama, Delhi.

1977 Raja Pagala Aur Teen Betiyaan, Hindi, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Kala Parishad, dir. B.V. Karanth (Bhopal Rang Manch 1978?).

1978 Lear, Marathi. readings, V. Karandikar, (tr.) Indian National Theatre, Bombay

1978 Mannan Lear, Tamil, tr. Aru Somasundaram.

1981 King Lear, Urdu, tr. Majnoon Gorakhpuri, dir. Barry John, NSD, Delhi.

1982 Teen Kanya, Bengali, tr./adapt. Amar Ghosh, in jatra form with Shamul Ghose.

1984-5 Nandabhupati, Kannada, tr. Gopal Vajpayee, dir. Jayatirtha Joshi, at Gadag, Dharwar.

1985 Hemchanda, Kannada, tr. Puttanna, dir. B.Suresh, Bangalore Chitra Abhinayaranga, Bangalore.

1986 Raja Lear, Bengali, tr./dir./actor Salil Bandhyopadhyay, Theatron, Calcutta.

1986 Raja Lear, Hindi, tr. Atul Tiwari dir. Fritz Bennewitz. NSD ?, Delhi.

1988 Raja Lear, Hindi, dir. Fritz Bennewitz, Padatik, Calcutta.

1988 Lear, Kannada, tr. H.S. Shiva Prakash, dir. Raghunandan, Tirugata (Repertory) Ninasam.

1980s Lear, Bengali, tr./dir. Amar Ghose. Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta,

(late)

1989 King Lear, Urdu/Hindi, tr./adapt. Neelabh, dir.Amal Allana, Television and Theatre Associates, Delhi.

1990s Lear, Kannada, tr./adapt. B Chandrashekar, for 2 chars, female’s story in flashback, by A. S. Murthy.

(early)

1991 Shakespeare Namaskara, Kannada. Scenes, dir. Fritz Bennewitz, Rangayana, Mysore.

1991 Lear, in Kathakali, dir. Leday and McRuvie, Bombay.

1992 Lear, Kannada, Sagar, one man show.

1993 Raja Lear, Marathi. tr. Vinda Karandikar, dir. Sharad Bhuthadia, Pratyaya, Kolhapur, performed over the decade in Bombay, all over Maharashtra, in Calcutta and in Kasargode.

1996 King Lear, English. Indian Summer Theatre Company, U.K.

1996 King Lear, English, dir. Arjun Raina, St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, Delhi, also in Calcutta.

1997 Samrat Lear, Hindi, tr. Bachchan, dir. J R. Brown, NSD, Delhi.

1997 Lear, Kannada, tr. H.S. Shiva Prakash, dir. B.V. Karanth, Prakash Karnataka Natya Akademy Drama Workshop for teachers, Mysore.

2001 Iruthiattam, Tamil tr./adapt. I. Parthasarthy, dir. R. Raju, Kasargode, also at Bharangam 2002, Delhi.

2002 Pagala Raja, Hindi, tr./adapt. Neelab, dir. C. Basavalingaiah, NSD, Delhi. less

Shakespeare in India: History of King Lear in India

King Lear is an appropriate play with which to illustrate these tendencies and periodisation in the performance history of Shakespeare in India.more

King Lear is an appropriate play with which to illustrate these tendencies and periodisation in the performance history of Shakespeare in India. One of the more frequently performed tragedies, it spans all these streams and periods and, in the last twenty years, particularly, it has become a kind of a measure or testing ground of actors and theatre groups. Its first performance in India was in 1832, when some scenes, in English, were done at the Chowringhee Theatre. Calcutta. During the period of ‘adapted’ Shakespeare, from the 1860s to the 1910s, in the 1880s a happy-ending version of Lear, Atipidacharita (The story of the intensely wronged one), influenced by Nahum Tate, in Marathi, became popular in Bombay. Another adapted and localized version, Safed Khoon (White Blood or Filial Treachery) by Agha Hashr Kashmiri, for the Parsi theatre in 1906, achieved commercial success and was played throughout the country.

1897 saw one of the first faithful translations, A. Govinda Pillai’s Malayalam version, Brittanile Rajavu Lear, being staged in Trivandrum, with a meticulous realism which included imported costumes and accessories, before a select audience and with a select cast – noted novelist and playwright C V Raman Pillai played Lear. However, as a performed text, the moment for King Lear in India arrives after independence. St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, Delhi, staged Lear in English, in 1962, with a young Roshan Seth – who went on to achieve greater recognition on the international stage and screen – as Lear. Ebrahim Alkazi, one of the foremost contemporary directors, produced a Raja Lear, in Urdu translation, for the National School of Drama in 1964, a production that has become a benchmark of the universalized Shakespeare. In the 1970s several productions in Hindi, Marathi and Tamil are to found, but it is in the eighties that the play comes fully into its own in India. As many as twenty one productions can be listed from this period, in several languages, including Bengali, Kannada, Hindi, Urdu, Marathi, Malayalam and Tamil, in all the different performative modes, of the localized, universalized, indigenised, English language and postcolonial Shakespeares.

Indian audiences have found many affinities with the story of King Lear. An Indian folk tale of an aging maharajah who is brought to grief when he puts the love-test to his three daughters before dividing his kingdom resonates with the same issues. He is shocked to hear the youngest daughter, his favourite, announce that she loves him like salt, a necessity – no more or less – and in anger disinherits her to suffer at the hands of the other two. The idea of banishment and exile as a form of penance, and suffering as atonement for wrongs committed are well-known concepts central to the great Indian epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata.

In everyday life, familial and generational conflict is familiar given the deeply patriarchal setup of Indian society. Further, the power struggle within a family and, by consequence, within the nation is reminiscent, for many readers/viewers, of the contemporary political scene in India where one family continues to be closely identified with the fortunes of the nation. It is the presence of such wide-ranging affinities from within their own culture, ancient and contemporary, that have made Indians take to Shakespeare in general, and King Lear in particular, in a big way. Shakespeare’s own setting of the play in a pre-Christian, quasi-pagan context, facilitates such equations. less

Related Productions

- Kral Lear (King Lear) (Kay, Malcolm Keith; 2012-2013)

- Kral Lear (King Lear) (Coleman, Basil; 1981)

- Kral “Soyatrım” Lear (“My Fool” King Lear) (Sertdemir, Yiğit; 2014)

- Rei Lear (King Lear) (Andreato, Elias; 2014)

- Samrat Lear (King Lear) (Brown, John Russell; 1997)