Shakespeare’s plays and motifs have been cited and appropriated in fragmentary forms on screen since motion pictures were invented in 1893 when the Kinetoscope was demonstrated in public for the first time. Allusions to Shakespeare haunt our contemporary culture in a myriad of ways, whether through brief references or sustained intertextual engagements.

For example, in a play-within-a-film, a production of Macbeth is interrupted in James McTeigue’s crime thriller The Raven (2012). Lady Macbeth’s lines are not fully audible, but her performance in the mad scene provides an additional layer of significance to the film’s main plot which revolves around a serial killer who commits murders following Edgar Allan Poe’s description in his stories.

In Tom Hooper’s biopic The King’s Speech (2010), Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech is recited in key scenes, suggesting that reciting Shakespeare might just cure stuttering. Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), a speech therapist for King George VI, also uses Caliban’s speech in an educational game with his children. In a film about a stuttering monarch learning to master the radio to speak to his subjects, the “voices in the air” that Caliban longs to hear become ironic. Both the king, who is struggling with speech disorders and is robbed of a voice, and his therapist, a subject from the Commonwealth who is more eloquent but id dismissed by the royal family.

Neither The Raven or The King’s Speech are Shakespeare films, but they evoke a range of themes and values associated with Shakespeare. Some scholars do reclaim such works as Shakespearean. A work does not have to be an adaptation to qualify as “Shakespearean,” writes Eric S. Mallin, whose work examines “movies that do not know they are Shakespeare plays.”

Shakespeare may not be the main focus of tattered, allusions in cinema, television, and theatre, but the canon remains a key factor in the cultural meanings of cinema. Even passing references to Shakespeare can have the power to shift the meanings and readings of a work.

For instance, “Shakespeare” is deployed as a reminder of human civilization in Miguel Sapochnik’s post-apocalyptic Finch (2021). In a philosophical scene that probes the question of what it means to be human, Finch Weinberg (Tom Hanks), the sole survivor, takes a humanoid robot he built into a derelict theatre to salvage food. It may seem coincidental in the plot, but clearly dramaturgically intentional, when that theatre turns out to be the venue for “Springfield Shakespeare Festival.”

The camera lingers frequently on the marquee with the word “Shakespeare” above the entrance. Inside the theatre, the android passes in front of a poster of a production of Much Ado About Nothing and spontaneously offers an analysis of that play in his monotonic, synthetic voice. His analysis, casual as it may seem, echoes the theme of post-apocalyptic mistrust: “This is a play by William Shakespeare, a dramatic comedy about love, deception, and other human misunders…”

Interestingly, while the android may appear to be analyzing the play, he is simply paraphrasing the taglines of the production, reading the analysis directly off of the poster. As it turns out, this is a pivotal scene where the android becomes sentient. He discovers himself for the first time in a mirror in the lobby. In a later scene, the android, in more fluid speech, tells Finch that he wishes to be named “William Shakespeare.” To have a name, for the android, is to be human.

Other instances contain direct quotations from Shakespeare for their indexical value to showcase a character’s intellect. In Destin Daniel Cretton’s Shang-Chi and The Legend of The Ten Rings (2021), Ben Kingsley’s actor-character Trevor Slattery tells Shang-Chi and Katy that he loves Shakespeare, while dressing like Shakespeare and displaying Shakespearean props and memorabilia from his acting career before his capture. Slattery proceeds to recite iconic lines from monologues in Macbeth and King Lear. Hands on his temples, in agony, Slattery says, in a dramatic tone: “Whence is that knocking? Wake Duncan with thy knocking!” Ever so proud of his performance of Macbeth, he tells Shang-Chi that “they couldn’t get enough of it. I’ve been doing weekly ghosts for lads ever since.” Volunteering to give his audience of two further “previews,” Slattery launches into the Fool’s speech in King Lear: “nuncle, nuncle, nuncle …” Beyond these fragmented quotations in a film that has nothing to do with Shakespeare, this meta-theatrical scene carries extra weight because Kingsley began his career at the Royal Shakespeare Company and starred in multiple Shakespearean productions. Onscreen, he is known for his performance of Feste in Trevor Nunn’s 1996 film version of Twelfth Night.

The study of “Shakespeare in tatters” and in fragmented citations differs from the study of adaptations of full Shakespearean plays.

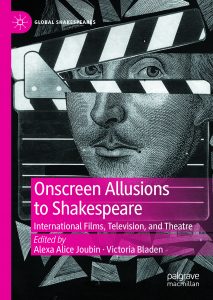

In Onscreen Allusions to Shakespeare, edited by Alexa Alice Joubin and Victoria Bladen, we ask: What is the effect of such allusions, whether fleeting references or rewritings inspired by a quote? Furthermore, what are the reception dynamics at play here among “knowing audiences” and amateurs? The meanings of tattered allusions emerge from the oscillation between hypotexts (earlier texts that inspire subsequent works) and hypertexts (texts with embedded allusions that one may or may not pursue).

Marjorie Garber reminds us that a well-chosen quotation used to be a gentleman’s calling card, a sign of membership in an elite club. Quoting the right authors at the right moment could signal one’s sophistication and class. The act of quoting others is simultaneously an act of deferral to an established authority as well as a form of ventriloquism that enables the speaker to channel that authority. Yet quotation can also be an act of resistance or challenge to the hypotext. Quoting or misquoting lines from Shakespeare carries with it the burden of previous uses of those lines, thus creating irony or solidarity as the case may be.

It is striking, but not coincidental, that the viability of quoting Shakespeare has frequently been critiqued and defended on ethical grounds. Fragmented references to Shakespeare–whether as direct quotations (often out of context) or visual echoes (such as a man holding up a skull)–signal linkage and distance to a cluster of texts. Screen references to Shakespeare are self-aware about their interdependence with other texts. Each new quotation both appears strange and estranges Shakespeare from itself; at the same time, every work creates some new strand within the ever-changing rhizome that comprises “Shakespeare.” Artists invoke Shakespeare for all sorts of reasons under many different guises, and our experience of these films is ghosted by our prior investments in select aspects of the play and in previous performances.

Allusions to Shakespeare, often out of context, are becoming more and more common, and they redefine the boundaries between Shakespearean and “not Shakespeare.” Onscreen Allusions to Shakespeare examines the issue of citation where a screen work may only briefly reference Shakespeare, in direct, implied or ambiguous ways. Nuanced and attenuated references to Shakespeare abound in screen culture. Moving away from the notion of singularity, these works carry with them diverse cultural significance.

_________________________

Excerpted from the Introduction to Onscreen Allusions to Shakespeare: International Film, Television, and Theatre, ed. Alexa Alice Joubin and Victoria Bladen (New York: Palgrave, 2022), pp. 1-12.

To read a sample chapter, click here.

This collection of essays extends beyond a US-UK axis to bring together an international group of scholars to explore Shakespearean appropriations in unexpected contexts in lesser-known films and television shows in India, Brazil, Russia, France, Australia, South Africa, East-Central Europe and Italy, with reference to some filmed stage works.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Onscreen Allusions to Shakespeare by Alexa Alice Joubin and Victoria Bladen

The Boundaries of Citation: Shakespeare in Davide Ferrario’s Tutta colpa di Giuda (2008), Alfredo Peyretti’s Moana (2009), and Connie Macatuno’s Rome and Juliet (2006) by Maurizio Calbi

Antipodean Shakespeares: Appropriating Shakespeare in Australian Film by Victoria Bladen

Othello Surfing: Fragments of Shakespeare in South Africa by Chris Thurman

Shakespeare in Bits and Bites in Indian Cinema by Poonam Trivedi

What “Doth Grace for Grace and Love for Love Allow”? Recreations of the Balcony Scenes on Brazilian Screens by Aimara da Cunha Resende

“Mon Petit Doigt M’a Dit …”: Referencing Shakespeare or Agatha Christie? by Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in Federico Fellini’s Roma by Mariacristina Cavecchi

“Still Our Contemporary” in East-Central Europe? Post-Socialist Shakespearean Allusions and Frameworks of Reference by Márta Minier

Soviet and Post-Soviet References to Hamlet on Film and Television by Boris N. Gaydin, Nikolay V. Zakharov

Afterword by Mark Thornton Burnett