Multiple Shakespearean characters lend themselves to be interpreted as transgender. Even though Shakespeare’s plays were initially performed by all-male casts, they were designed to appeal to diverse audiences. Shakespeare’s plays, as readily available reference points, have been reimagined in performances that explore new gender roles. In particular, transgender performances tend to be billed, or perceived, as art with a cause, as a socially reparative act leading to the amelioration of personal and social circumstances. Reparative trans performances—works in which characters see their condition improve—carry substantial affective rewards by offering optimism and emotional gratification. The call for social justice may seem universal, but the exact elements requiring reparation are malleable. The reparative arcs diverge dramatically between different works.

There are two strands of reparative performance:

There are two strands of reparative performance:

(1) the open-ended amelioration of injustices by enabling characters’ self-realization and by calling on audiences to recognize that trans bodies do not require “reparation”; and

(2) narratives that showcase directive and regressive changes organized around “restoring” trans characters to perceived norms of binary gender and heterosexuality.

Both approaches seek to diagnose and correct unjust conditions, though they diverge in their interpretations of the source of trouble. The first approach empowers socially marginalized characters, while the second approach caters to (mostly) cis-heterosexual audiences’ binary imaginations.

Taking the second, conservative approach, Richard Eyre’s Othello-inspired film Stage Beauty (2004) offers cis-heteronormative “corrections” of their characters. The film chronicles the private life and stage career of the historical Edward (Ned) Kynaston (1640–1712), who plays exclusively female roles before taking on male roles onstage. The renowned Restoration adult “boy actor,” “the last of his kind” according to the film’s tagline, specializes in playing such female roles as Desdemona in Othello. He also presents as female in his romantic life. Eventually he “straightens up” by playing Othello onstage and by falling in love with an actress after his male lover leaves him and after King Charles II bans men from playing women.

Based on Jeffrey Hatcher’s play Compleat Female Stage Beauty, the film Stage Beauty centers on the question “Who am I?” in the career and private life of Billy Crudup’s character Ned Kynaston, one of the last Restoration adult “boy actors” who exclusively played female roles. The film explores the boundaries between cross-gender casting (Kynaston as Desdemona), drag (Kynaston’s playful female persona in private life), proto-trans (Kynaston’s male lover’s statement), and transgender identities (Kynaston’s statement about himself).

Stage Beauty recruits the audience to participate in Kynaston’s affective labor toward becoming who the society thinks he “should” be. The film “redeems” Kynaston by having him straighten up through a “reparative arc” from a trans feminine person with a male lover to a cis man in love with a cis woman, Maria.

Kynaston presents as female in bed with his dominant lover George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham (Ben Chaplin). They meet regularly in the theater where Kynaston performs. As Kynaston approaches the duke, he brushes off Kynaston’s affectionate feminine gestures, insisting that Kynaston wear a wig before coming to bed. Kynaston retorts playfully, “Do you ask your lady whores to wear a wig to bed?” alluding to the duke’s sexually promiscuous lifestyle. Kynaston wishes to know why the duke treats his cis-bodied sexual partners differently from him. The duke explains that the wig is necessary to make Kynaston “more of a woman.” Alluding to the destructive nature of erotic desires and the Renaissance trope relating orgasm and death, the duke says to Kynaston, “I like to see a golden flow as I die in you.” There is also a connection among sex, death, and stage performance of femininity.

There is an irony in their relationship, however. Their illicit encounters—carefully kept under wraps—always take place onstage after Kynaston’s evening performance. This is parallel to Gong-gil’s relationship with the king discussed earlier, in which Gong-gil is always asked to put on private shadow plays or finger puppet shows for the king. They converse in a coded manner under the guise of discussing theater works. In Stage Beauty, after the audiences clear the auditorium, Kynaston leaves the role of Desdemona behind only to return in the same costume to the same bed and stage set where he, as Desdemona, has just been murdered. Waiting for Kynaston in bed is the duke. The setting of the stage gives their relationship a theatrical quality. The duke’s insistence on Kynaston’s donning wigs and dresses further accentuates the idea that Kynaston puts on a second show each evening, a private show for an audience of one on a public stage. It is a private act in a public space.

The duke’s attachment to such gendered accessories as the wig harks back to similar scenes of “trans revelation” in other films. The “gender reveal” scenes in both films echo Talia Mae Bettcher’s argument that the misconception of an anatomical reality of gender casts trans people as “evil . . . make-believers,” locking them into being either a visible pretender or an invisible deceiver to be forcefully exposed at some point. Either way they are seen as “fundamentally illusory.” Kynaston pushes back on the idea that the wig alone makes him a woman.

The key event in the “straightening up” of Kynaston’s gender is his rupture with his boyfriend. Kynaston meets with the duke to ask why Buckingham has not visited him recently. He attempts, as he does in the past, playful affection, but the duke rejects him. Upon learning that the duke is marrying a cis woman, Kynaston presses in a competitive tone: “What is she like in bed? What is she like to kiss?” The duke eventually acknowledges that he valued their relationship as no more than a performance, a fetish: “When we were in bed, it was always in a bed onstage. I’d think, here I am in a play, inside Desdemona, Cleopatra, poor Ophelia. You’re none of them now. I don’t know who you are. I doubt you do.” Now that Kynaston no longer plays women onstage, the duke cannot accept him as he is: “I don’t want you! What you are now.” It becomes clear that Kynaston is a temporary substitute in bed until the duke lands a cis partner.

Stage Beauty showcases processes of gendered “becoming.” Kynaston re-inscribe the sexed body into social-constructivist discourses about gender while simultaneously countering the idea that anatomy is their destiny.

————-

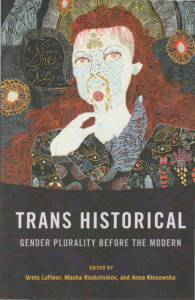

Excerpted from Alexa Alice Joubin’s “Performing Reparative Transgender Identities from Stage Beauty to The King and the Clown,” in Trans Historical: Gender Plurality before the Modern, ed. Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Klosowska (Cornell University Press, 2021), 322-349; full text available here.