Excerpted from “The Paradox of Female Agency: Ophelia and East Asian Sensibilities,” in The Afterlife of Ophelia, ed. Kaara Peterson and Deanne Williams. New York: Palgrave, 2012. pp. 79-100

Full text available gwu.academia.edu/joubin

The Paradox of Female Agency:

Ophelia and East Asian Sensibilities

There has always been a perceived affinity between Ophelia and East Asian women. In May 1930, Evelyn Waugh entertained the prospect of Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong playing Ophelia: “I should like to see Miss Wong playing Shakespeare. Why not a Chinese Ophelia? It seems to me that Miss Wong has exactly those attributes which one most requires of Shakespearean heroines.” [i] Ophelia is a paradox in East Asian literature, drama and film. Even when she appears to depend on others for her thoughts like her Western counterpart, the figure of Ophelia in Asian rewritings signals a strong presence by her absence and even absent-mindedness. While Asian Ophelias may suffer from what S. I. Hayakawa calls “the Ophelia syndrome” (inability to formulate and express one’s own thoughts), they adopt various rhetorical strategies—balancing between eloquence and silence—to let themselves be seen and heard. [ii] Asian incarnations of Ophelias occupy a broad spectrum of interpretive range and possess more moral agency.

There are three main approaches to interpreting East Asian Ophelias. The first is informed by the fascination with and reaction against the Victorian pictorialization of Ophelia, especially John Everett Millais’s famous Ophelia (1851), that emphasized, as Kimberly Rhodes describes, her “pathos, innocence, and beauty rather than the unseemly detail of her death.” [iii] Despite having lived through negative experiences, Ophelia retains a childlike innocence in these rewritings. For example, New Hamlet by Lao She (penname of Shu Qingchun, 1899-1966) parodies China’s “Hamlet complex” (the inability to act at a time of national crisis) and the fascination with an Ophelia submerged in water. Both Ophelia and Millais’s painting are featured in two of Japanese writer Natsume Sōseki’s early twentieth-century novels. A second approach emphasizes the local context. Adapters used local values to engage with and even critique the Victorian narrative tradition of moralization. Late nineteenth-century translator Lin Shu (1852-1924), for example, tones down the sentimentalization of Ophelia in his classical Chinese rewriting of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, showcasing the conflict between Victorian and Confucian moral codes. The third approach focuses upon an objectified and sexualized Ophelia. As other chapters in this volume demonstrate, this is not exclusively an Asian phenomenon. However, the eroticism associated with the Ophelia figure in a number of Asian stage and screen versions of Hamlet, such as Sherwood Hu’s film Prince of the Himalayas (2006), aligns Ophelia with East Asian ideals of femininity, but also brings out the sexuality that is latent or suppressed in Victorian interpretations. They do so by aligning Ophelia with East Asian ideals of femininity.

“Fair Ophelia” in the Victorian Legacy and Modern Parody

John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1851).

In conversation with and moving beyond the Victorian legacy, Ophelia has been reimagined in Asian culture as a filial daughter, river goddess, an ideal lover, and a mediator between human and spiritual worlds. As they race to “botch [her] words up” (4.5.10) and tell Ophelia’s stories, Asian artists present an Ophelia figure who is no longer just a “document in madness” (4.5.178). In fact, Ophelia is so central to the anxiety of modernity that she remains a focal point on the Japanese stage even when Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy and other soliloquies were cut completely in early adaptations and performances in Tokyo and elsewhere. The first production of Hamlet in Japan, a kabuki adaptation around 1890, and the first performance of Hamlet in Tokyo in 1903, both

indulged in the spectacle of the mad Ophelia. Significantly the 1930 Tokyo production became a landmark event in Japan’s theatre and cultural history because Orieko (Ophelia) was played by an actress (Madame Sadayacco) rather than the customary onnagata, or female impersonator. [iv] This western performance technique was used to offer an Asian take on Ophelia, as the production was set in contemporary Japan.

The Victorian legacy has served as an iconic reference point for later artists and shaped Ophelia’s afterlife. Rhiannon Brace describes The Ophelia Project (2010) which she directed in London, as “a celebration of woman,” that drew upon “romantic images of women such as Millais’s Ophelia and other Pre-Raphaelite paintings [and their glorification of Nature] to create movement.” [v] Natsume Sōseki created a painter obsessed by Millais’ Ophelia in his Kusamakura (1906), and one obsessed by the likeness of Ophelia herself in a portrait in Kojin, A Wanderer (1912-13). [vi] Lao She’s novella New Hamlet (1936) and Sherwood Hu’s film The Prince of the Himalayas (2006) were also inspired by this iconic painting, which was exhibited in Tokyo and Kobe in 1997-8, and is well known to East Asian audiences. Ophelia, crowned by a floral wreath and floating in a lake, dominates one of the posters for Prince of the Himalayas, while Lao She’s novella creates an ironic distance from such unnatural naturalism and gendered poses that modern adapters have inherited from the pre-Raphaelite ideal.

Ophelia as Goddess and Lover on Screen

VIDEO: /prince-of-himalayas-hu-sherwood-2006/

Shot in Tibet with an all-Tibetan cast, Sherwood Hu’s Prince of the Himalayas offers a visual response to Millais’s representation of the drowning Ophelia. [vii] Tibetan actress Sonamdolgar as Odsaluyang presents a feisty and assertive Ophelia who links the secular with the sacred, and death with life. Ophelia is associated with water throughout the film, calling to mind the drenched and drowned Ophelias in Kenneth Branagh’s and Michael Almereyda’s film versions. Early on, we are shown a rather explicit, intimate scene between Prince Lhamoklodan (Hamlet) and Odsaluyang in her hut by a stream, after which Ophelia becomes pregnant (the two are not married). In labor, Odsaluyang approaches the Namtso Lake, a sacred site to Tibetan pilgrims, in search of the prince, whom she loves, but also hates, for killing her father. It seems that she walks into the lake to ease her pain, but the scene presents a haunting image of Ophelia’s death that amounts to a visual citation of Millais’s painting. Picking wild flowers and wearing a white garment with a floral wreath on her head, she lies down and floats on water, giving birth to her and Hamlet’s child before “sinking down to the river bed in deep sleep” where she “meets her father and mother.” [viii] The camera pans over the water to give us a glimpse of the baby floating away from the mother. Presumably she dies after giving birth in the lake, but her death is not depicted on screen.

VIDEO: http://youtu.be/PeHIj3Y4ysk

This scene takes Ophelia’s association with the cyclic quality of nature in Millais to a different level, hinting at the necessary, if cruel, procession of fading and emerging generations. Both Millais’s and Hu’s works are part of the historical fascinating with Ophelia’s death and reports of drowned girls. [ix] Painted along the banks of the idyllic Hogsmill River in Surrey, Millais’ Ophelia espouses a dramatic quality because it focuses thematically on the cycle of growth and decay and the transitional moment between life and death. [x] Buoyed temporarily by the stream, the dying Ophelia is half sunk but her head is still above the water. More importantly, as Stuart Sillars points out, the painting functions as “both an anticipation and a deferral of mourning” by crystallizing this particular moment before death. [xi] Likewise, this scene is depicted in a painterly mode in Hu’s film to focus attention on Ophelia’s suffering. As Odsaluyang walks into the lake singing a song, the water runs red with her blood. The baby is carried by water to safety and rescued by the Wolf Woman, a prophet. As one of the most interesting departures from Hamlet, this scene hints at the possibility of a saintly Ophelia who, in her death, brings forth a new life and hope for the next generation. Prince of the Himalayas offers a courageous, independent Ophelia.

Sonamdolgar as Odsaluyang (Ophelia) in Prince of the Himalayas. Having given birth to her and Lhamoklodan’s (Hamlet) baby, she dies in the lake. The film was shot in Tibet with an all-Tibetan cast.

If Gertrude’s account of Ophelia recasts her as a fairy-tale creature (“mermaid-like,” 4.7.176), Odsaluyang in Prince of the Himalayas is a kind of goddess of nature, an immortal bride who returns to Nature. The strong association between water and suffering women in Chinese art and film history contributed to Hu’s decision to shoot Ophelia’s death scene by the mirror-like Namtso Lake near Lhasa. Water might play the role of a mirror of beauty or a gateway to darker realities lying beneath its surface. Female water deities celebrated in Chinese poetry and paintings “ruled the waves” and water can be “a mirror of beauty or for the darker possibilities hidden below its surface” (175). [xii] Hu’s film associates Ophelia with a water goddess not unlike the Luo River Goddess or the Goddesses of the Xiang River. She is a source of danger but also of rebirth. Such goddesses, according to legends, start out as “unhappy spirits of drowned victims involved in female sacrifice, young girls given in local rituals as brides to pacify male river gods. Others may have been romantic love suicides (nobly following their deceased husbands) … or victims of no-love situations… while still others represented punishment for female sexual transgression” (175). Prince of the Himalayas literally gives birth to a more sexual as well as spiritual vision of Ophelia in the water.

A similarly innocent yet assertive Ophelia emerges from Chinese director Feng Xiaogang’s 2006 The Banquet (aka The Legend of the Black Scorpion), a high-profile kung fu period epic set in fifth-century China with an all-star cast. [xiii]

VIDEO: /the-banquet-feng-xiaogang-2006/

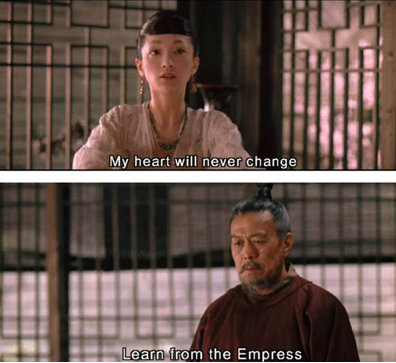

Feng is a household name in China, known for his invention of a new genre, the comic and often farcical “New Year celebration film” screened during the Chinese new year. Highly profitable and entertaining, the genre subverts the didacticism that is standard fare in films produced by state studios. The Banquet’s Ophelia (Qing Nü, played by Zhou Xun) dominates many scenes with her songs and dance, and is not shy about expressing her affection for Hamlet (Prince Wu Luan, played by Daniel Wu) even when she is threatened by the Gertrude figure (Empress Wan, played by Zhang Ziyi), who is both the prince’s step mother and lover. Significantly, Ophelia does not go mad. While her songs allude to rivers and boating, and her intimate scene with Hamlet involves rain, Ophelia is not drowned in the end.

This bold cinematic re-imagination of Hamlet shifts the focus from the question of interiority–traditionally embodied by Hamlet–to an ambitious, articulate Gertrude (Empress Wan) and an assertive Ophelia (Qing Nü): both characters do not hesitate to express their love for the prince. Empress Wan is the prince’s stepmother and she has kept her romantic relationship with him under wraps. Qing Nü’s naïveté and purity make her a desirable yet unattainable figure of hope, in contrast to the calculating empress, and as an ideal contrast to China’s postsocialist society that is driven by a new market economy that turns everything, including romance and love, into a commodity. [xiv] Instead, she is innocent, passionate, and bold.

Despite China’s economic growth, censorship continues to pose a challenge to artists. In the film, Qing Nü shuns traditional methods of communication altogether. In response to Empress Wan’s probing question as to whether Qing Nü has received any letters from the prince, she offers a bold answer: “we never exchange letters.” She also speaks of her dreams openly: “The prince always comes in my dreams. He came last night as well.” She admits this with a sense of pride.

The Banquet turns Ophelia into a symbol of innocence in a court of violence and intrigue. Significantly, for a martial arts film, Qing Nü is the only character not versed in swordsmanship, and her only weapons are her perseverance in the face of insurmountable obstacles and headstrong adherence to her love for the prince. Her name, Qing Nü, derives from the goddess of snow in Chinese mythology, and her robes are almost always white regardless of the occasion. This highlights the idea of chastity, as snow is used as a trope for chaste women in traditional poetry. [xv] Qing Nü is uninterested in politics, and refuses to succumb to her father’s advice to “learn from the empress” and use marriage as a political stepping-stone. Empress Wan, by contrast, marries her brother-in-law in exchange for power and security after her husband is killed by a scorpion’s sting.

Fig. 2. Zhou Xun as Qing Nü in The Banquet, directed by Feng Xiaogang (2006).

Yet Qing Nü’s innocence and dedication do not translate into childishness. In response to her brother’s reminder that “you are not in [the prince’s] heart. Do not fool yourself,” Qing Nü indicates that she is fully aware of the situation, but she has “promised to always wait for him.” She chooses to stay by his side and sing to him so that he will not be lonely. The consequences are painful. Jealous of Qing Nü’s intimacy with the prince and her ability to offer unconditional love, Empress Wan orders her to be whipped. Ever defiant and refusing to be manipulated by anyone, Qing Nü almost gets her face branded by the Empress.

Qing Nü (Ophelia) debates her father (Polonius) on love and her relationship with Prince Wu Luan (Hamlet) in The Banquet, directed by Feng Xiaogang (2006).

VIDEO: http://youtu.be/qBsEu9PU71s

Qing Nü also publicly expresses her love for the prince. When Wu Luan is being sent by Emperor Li as a hostage to the Khitans, a nomadic people in northwestern China, Qing Nü petitions in front of the court to be allowed to go along, echoing Desdemona’s insistence on accompanying Othello to Cyprus. Her passions are uncensored, and her reasons simple: so that the prince will not be lonely. Unlike Shakespeare’s Ophelia Qing Nü does not have to go mad or speak allusively to express herself, though she sings on multiple occasions just like Ophelia does in Hamlet. Toward the end of the film at the banquet celebrating the coronation of the empress, she sings a song of solitude that the prince had taught her, and leads a group dance:

VIDEO: http://youtu.be/PrewEztjGLs

What blessed night is this?

Drifting down the river Qian.

What auspicious day is this?

On the boat with my Prince.

Too bashful to stare,

A secret I cannot share.

My heart is filled with longing.

Longing to know you, dear Prince.

Trees live on mountains,

And branches live on trees.

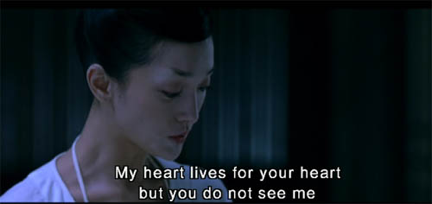

My heart lives for your heart,

But you do not see me.

Qing Nü (Ophelia) singing in The Banquet, directed by Feng Xiaogang (2006).

She seems to be content to simply love the prince without seeking anything in return. Qing Nü’s entrance takes Emperor Li and Empress Wan by surprise: her performance at the court commemorates her lover who has been presumed dead en route to the Khitans (although, unbeknownst to Qing Nü and everyone in the court, the prince has returned and is disguising himself as one of the masked dancers).

Qing Nü’s accidental death at the hands of the Empress has more in common with Shakespeare’s Claudius or Gertrude than Ophelia: she drinks from a poisoned cup the Empress intends for the Emperor.

Qing Nü’s (Ophelia) last words to the prince.

Ever a saintly presence, Qing Nü addresses her last words to the prince: “Do you still feel lonely?” Mourning Qing Nü’s demise, the prince, a kung fu master, finally moves forward with his revenge plan. Ophelia’s fatal drop from the willow tree into the stream in Hamlet is thus replaced by Qing Nü’s selfless sacrifice and symbolic purging of the court’s collective sins in The Banquet. The Ophelia figure therefore represents ideal femininity in the face of a dysfunctional political structure. [xvi]

Ophelia as Mediator on Stage

In Korea, the dilemma Ophelia faces between her father and brother on the one hand, and the prince on the other, has been considered by directors and critics as a parallel to the situations of “Korean women constricted by Confucian conventions.” [xvii] While Confucian constrictions can undermine a woman’s agency, in the East Asian dramatic tradition oppressed women gain an upper hand when they return as ghosts or act as mediators in religious contexts. As a result, multiple stage “shamanistic” adaptations in Korea have recast her as a mediator or a medium possessed by a ghost. While Millais’s painting highlights the transitional moment between life and death, Korean adaptations present Ophelia as a shaman who serves as a medium to connect the worlds of the living and dead. As Hyon-u Lee suggests, the Korean fascination with Ophelia coincides with the rise of Korean feminism in the 1990s. [xviii] And shamanism, which resides outside the Confucian social structure, gives women greater agency. [xix]

Kim Jung-ok’s Hamlet (1993) is staged under an enormous hemp cloth that is suspended from the ceiling to resemble a house of mourning. It is customary for a mourning son to wear coarse hemp clothing, because hemp cloth is associated with funerals. Appropriately enough, the play begins with Ophelia’s funeral. Possessed by the Old King’s spirit, Ophelia conveys the story of his murder. [xx] Kim Kwang-bo’s Ophelia: Sister, Come to My Bed (1995) also opens with Ophelia’s funeral. Caught between the incestuous love of Laertes and romantic love of Hamlet, Ophelia is eventually abandoned by both men: there is no future with Laertes, and Hamlet must carry out his revenge mission. Following Kim Jung-ok’s adaptation, Ophelia is possessed by Old Hamlet’s spirit: she urges Hamlet to avenge his father’s death. When she is possessed by the ghost of Old Hamlet (a large puppet operated by three monks), Ophelia moves in unison with the ghost and changes her voice to that of an old man (“Hamlet, my son!”). [xxi] Like Qing Nü, Korean Ophelias are both the mediators and agents of change, consoling the dead and guiding the living. The use of shamanism as a thematic structure reminds us, also, that Hamlet was perhaps a way to exorcise the painful loss of a son by its author.

Transnational productions designed for international festivals espouse a different attitude toward Ophelia and her world. These works are often more self-reflexive and conscious of the transformation of Shakespeare’s Ophelia into an icon in an age of globalization. Staged at the Hamlet Sommer festival in Kronberg Castle, Denmark, Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s Search: Hamlet (2002) featured Dicte, a Danish rock singer who wrote the score, sang, and performed in the dance theatre event. Ong uses the conceptual question, “Who is Hamlet in our time?” to pull together a diverse group and material. Although the main character, Hamlet, was missing, Ophelia was represented as an astute observer of events.

VIDEO: /search-hamlet-ong-keng-sen-2002-two/

Dicte as Ophelia and Carlotta Ikeda as the Ghost in Ong Keng Sen’s Search: Hamlet at the Kronborg Castle, Denmark, 2002.

The performance took place in different rooms of the castle and gradually descended into a courtyard connected by runways: a detail appropriated from the hanamichi bridge (flower way) of Kabuki theatre. Following the style of a Noh play, Search: Hamlet contained five “books,” each of which offered a different version of the events in Hamlet from a different perspective: Book of the Ghost, Book of the Warrior (Laertes), Book of the Young Girl (Ophelia), Book of the Mad Woman (Gertrude), and Book of the Demon (Claudius). Dicte’s song for Ophelia interrogates the various stereotypes associated with her Shakespearean character. She does so, notably, in the third person:

Ophelia: She is said to be sad

She’s just fateful

Is that bad

So in love

So in love

She is said to be sad

She’s just fragile

Obedient

So in love

So in love

She is said to be sad

Weak and violent

She’ll go mad

Hold her tongue

Hold her tongue

She is said to be sad

Look how pale blue

Turns to black

Sick at heart

Sick at heart

She is said to be sad

Now she’s weightless

Is that bad

Where’s her heart

Where’s her heart [xxii]

No longer a “green girl” (1.3.101), Ophelia speaks freely of herself in third person as an observer (4.5.4). Gilda Rosie Krantz III (Ann Crosset), an outsider, immediately retorts, “That’s not true,” and urges her to “stop dreaming and get changed.” But daydreaming is the last thing this powerful performance seeks to induce. Its multi-national cast highlights the connections between its diverse sites of origin—Asia, Europe, America. Wandering through this landscape is Ophelia the singer, who appears in three of the five books. Her songs offer astute observations of her alter ego in Shakespeare’s play and provide advice on love to others.

Ophelia in Popular Culture

Though the significance of her incoherent presence is challenging to grasp, Ophelia has a central place as a symbol of abuse victim in popular, teen, and performance cultures. [xxiii] She has achieved cult status in some parts of East Asia thanks in part to Hamlet’s global reputation, but her story is often taken out of the Shakespearean context of signification. Two different sets of high-thread count cotton bedding are sold in China and Taiwan under the name “Ophelia,” and the packaging—catering to the high-end market—associates the name with quality, joy, and modern life. [xxiv] Ophelia is also the name of a self-made heroine with compassionate instincts in a Chinese online video game that has little to do with any Shakespearean source.

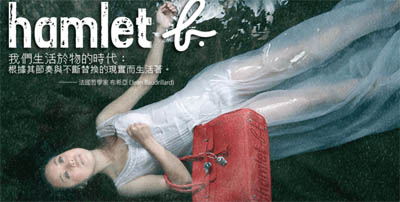

A recent adaptation entitled Hamletmaxhine-hamlet b (2010) was staged in Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Taipei. This production takes a grim view of Ophelia as a globally circulating icon. [xxv] Quoting from Jean Baudrillard, it is based in part on Heiner Müller’s Hamletmachine (the German playwright even made a guest appearance working on the script on a typewriter). The play explores modern consumer culture and the future of the “culture industry” through installation art and fragmented monologues. The performance space in a black box theatre was designed to resemble a digital screen. Frames large enough for the performers to walk through were hanging to the left and right, and images and texts were projected to the white ceiling. Hamlet’s revenge mission is irrelevant because this Hamlet is a street artist whose “performance” as an avenger was bought for private consumption by a rich patron. A fan of Hamlet, Ophelia goes to great length to pursue her idol, only to discover that the man in front of her is one of the many mindless, digitally-reproduced avatars—fleeting simulations of the real.

One of the most striking scenes involved Ophelia floating in the streams on stage, clutching a crimson luxury handbag. The scene, accompanied by a tagline taken from Baudrillard, dominated the poster:

We live by object time; by this I mean we live by the pace of objects, live to the rhythm to their ceaseless succession. [xxvi]

Hamletmaxhine-hamlet. b co-produced by Hong Kong On & On Theatre Workshop and Taipei’s Mobius Strip Theatre (2010).

It is notable that Ophelia blinks her eyes as she enjoys what appeared to be a spa experience, rather than a “return” to mother nature as a consequence of a suicide or fatal accident. A parodic visual citation of Millais’s sentimental Ophelia, the figure of Ophelia in this production becomes a vehicle for commentary on the endless precession of simulacra. She first appears as a black female mannequin, clad in a white fluffy skirt and hanging from the ceiling. The audience watches on through a frame that symbolizes a screen. The message from a world of simulacra is driven home when all the actors cross-dress to become Ophelia as the mannequin is lowered onto the stage.

VIDEO: http://youtu.be/E8EKnCaX1mw

Ninagawa’s Hamlet (1995), privileges local, rather than international, contexts. Ophelia follows the Japanese custom of arranging ornate hina dolls on tiers—a pastime for ladies at the court.

The dolls will eventually be set afloat to carry misfortunes away so that the children of the house can grow up healthy. Since the dolls represent hope, Ophelia’s giving away dolls rather than flowers in her mad scene carries with it a grave tone. The metaphorical connection between drowning—dolls adrift—and despair is also evident. Ophelia has also been more freely appropriated and loaded with local significance.

Angel’s Kiss (1998), a South Korean Internet novel by Son Young Mok that has no other connection to Hamlet, concludes with a two-part epilogue entitled “A neurotic Hamlet and pregnant Ophelia.” The novel chronicles the romantic adventures of a handsome movie actor and his amnesiac wife who treats him as a stranger. In the end, they fall in love all over again, and, oddly enough, evoked as Hamlet and Ophelia, convenient shorthand for unfailing love. The same pattern is evident in Shi Jisheng’s “A Sonnet for Ophelia” (1983)—an ode to romantic love detached from the context of Hamlet—and Wu Zhenhuan’s “Ophelia” (2008), among other creative works in Chinese. [xxvii] Wu’s poem alludes to Hamlet by connecting a “feeble girl” to the departure and arrival of a mysterious man—her only “curse and blessing.” [xxviii]

Conclusion

East Asian rewritings transform Ophelia from “a document of madness” (4.5.178) to symbols of purity and female agency, privileged sites of resistance of authority, and an icon of true love. These adaptations of Hamlet are preoccupied with their placement and displacement in relation to sources of authority. While her songs still occupy the center of attention, Ophelia does not tend to stand in for lost girlhood or female madness in Asia. Instead, the strands of girl power and fragile girlhood coexist as Asian Ophelias lay claim to their moral agency by thinking and acting on their own behalf. However, they are simultaneously limited by the new cultural locations they seek to sustain. In some instances, the double bind of Confucian ethical codes and East Asian modernity contribute to contrasting interpretations of Ophelia that make her, at once, a powerful mediator and a symbol of the abject. In other instances, these powerful rewritings serve as inspiration for local artists and audiences, for spawning new images of modern women. In still other instances, the figure of Ophelia is pitched as a cross between a conscientious and filial Cordelia, an innocent Desdemona, a loyal subject, and a fearless and dedicated lover.

Though it is necessary to highlight the female agency in the local contexts, these examples do not seek to privilege any version of local feminism or to posit a nationalist category of “Asian” women. [xxix] On the contrary, they slow us down, defamiliarize what has been assumed to be familiar, and help focus our attention as we “return” from translation and adaptation. [xxx] They lead us back to Shakespeare’s plays with new paths for interpretation. The artistic achievements of these interpretations of Ophelia lie in the rich and complex pictures of love, social responsibility, and transcendence that they can offer. As much as Ophelia was freely appropriated as a privileged site of female agency in local contexts, writers and directors have also parodied the constructions of female madness and unrequited love through Ophelia. Indeed, as Elaine Showalter argues, there may be no “true” Ophelia for whom “feminist criticism must unambiguously speak,” a variety of images of East Asian women emerge through these rewritings. [xxxi]

Notes

[i] Waugh went on to say that “I cannot see her as Lady Macbeth, but she seems to me perfectly suited for the role of Juliet or to any of the heroines of the comedies.” Evelyn Waugh, “My Favourite Film Star,” The Daily Mail, 24 May 1930. I thank Jonathan Hsy for bringing the text to my attention.

[ii] See S. I. Hayakawa, “What Does It Mean to Be Creative?” Through the Communication Barrier, ed. Arthur Chandler (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 104-105; see also “News and Notes,” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 284. 6327 (May 15, 1982): 1483. This is not to be confused with popular usage of the term that has little to do with Hamlet or Ophelia, such as the pop/rock band Ophelia Syndrome that was formed in 1998.

[iii] Kimberly Rhodes, Ophelia and Victorian Visual Culture (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2008), p. 89

[iv] Yasunari Takahashi, “Hamlet and the Anxiety of Modern Japan,” Shakespeare Survey 48 (1995): 99-111.

[v] The Ophelia Collective, a collective of female dancers and choreographers, staged The Ophelia Project (dir. Rhiannon Brace), a hybrid stage work of physical theatre and contemporary dance, to celebrate womanhood. The work was staged at the Robin Howard Dance Theatre at the Place in London in January, 2011; quotation taken from http://www.theromanticrevolution.co.uk/, accessed December 1, 2010.

[vi] Shihoko Hamada, “Kojin and Hamlet: The Madness of Hamlet, Ophelia, and Ichiro,” Comparative Studies 33.1 (1996): 59-68.

[vii] Prince of the Himalayas. Dir. Sherwood Hu. Perf. Purba Rgyal, Dobrgyal, Zomskyid. Hus entertainment, 2006. DVD. The film was screened at the Shakespeare Association of America’s annual meeting in Bellevue in April, 2011.

[viii] Pang Bei, ed., Ximalaya wangzi [Prince of the Himalayas] (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publisher, 2006), 54.

[ix] BBC recently reported Steven Gunn’s discovery of the “real” Ophelia, a Tudor coroner’s report that sheds light on the drowning of Jane Shaxspere in a millpond near Stratford-upon-Avon in 1569, who may be a young cousin of William Shakespeare. Sean Coughlan, “Tudor coroners’ records give clue to ‘real Ophelia’ for Shakespeare,” BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-13682993, accessed June 7, 2011.

[x] Barbara C.L. Webb, Millais and the Hogsmill River (B. Webb, 1997). For studies of Shakespeare in Victorian art, see John Christian, “Shakespeare in Victorian Art,” in Shakespeare in Art, ed. Jane Martineau et al. (London: Merrell, 2003), 217–21; and Stuart Sillars, Painting Shakespeare: The Artist as Critic, 1720–1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 306.

[xi] Stuart Sillars, Shakespeare, Time and the Victorians: A Pictorial Exploration(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 77.

[xii] Jerome Silbergeld, China into Film: Frames of Reference in Contemporary Chinese Cinema (London: Reaktion Books, 1999), 175.

[xiii] This film was screened at the 2008 annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America in Dallas. The Banquet. Dir. Feng Xiaogang. Perf. Zhang Ziyi, Ge You, Daniel Wu, Zhou Xun. Music by Tan Dun. Media Asia Films, 2006. DVD.

[xiv] Cf. Jason McGrath, Postsocialist Modernity: Chinese Cinema, Literature, and Criticism in the Market Age (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), 1-24.

[xv] Ciyuan (Chinese Dictionary of Etymology), Revised Edition, ed. Shangwu yinshuguan Editorial Committee. Beijing: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1997, p. 1823.

[xvi] Hamlet’s gender identity has also been reconfigured. See Yu Jin Ko, “Martial Arts and Masculine Identity in Feng Xiaogang’s The Banquet.” In Asian Shakespeares on Screen: Two Films in Perspective. Special issue, edited by Alexa Huang. Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 4.2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Available online: http://www.borrowers.uga.edu/

[xvii] Hyon-u Lee, “Shamanism in Korean Hamlets since 1990: Exorcising Han,” Special Issue on Shakespeare, Asian Theatre Journal, ed. Alexa Huang, 28.1 (Spring 2011): 104-128.

[xviii] Lee, “Shamanism in Korean Hamlets,” 114.

[xix] Janice C. H. Kim, “Processes of Feminine Power: Shamans in Central Korea,” Korean Shamanism: Revivals, Survivals, and Change, ed. Keith Howard (Seoul: Seoul Press, 1998), 113-132.

[xx] Alexa Alice Joubin and Peter Donaldson, eds., Global Shakespeares (http://globalshakespeares.mit.edu). Korean co-editor Hyon-u Lee. Accessed May 2011. Another example is Bae Yo-sup’s Hamlet Cantabile (2005, 2007, 2008).

[xxi] Jo Kwang-hwa, Ophelia, Nu-eeyu, N-e Chimshilo, script. Translation by Lee, “Shamanism in Korean Hamlets,” 109.

[xxii] Ong Keng Sen, Search: Hamlet. Unpublished script (2003), p.3.

[xxiii] As evidenced by American writer Lisa Klein’s Ophelia and “The Book of the Young Girl”—part of Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s stage work Search: Hamlet in Kronborg Castle, Denmark. Some adaptations present her as a pathological woman, while others construct a more assertive Ophelia, such as Twelve Ophelias by Caridad Svich and Ophelia Thinks Harder by Jean Bretts. Richard Schechner recently directed an unsettling “performance-in-progress” entitled Imagining O at the University of Kent to explore Ophelia’s descent into madness and suicide (July 2011).

[xxiv] Ophelia and other characters, along with their dialogues, are also being distilled to construct notions of innocence and love in such musicals as With Love, William Shakespeare staged by Theatre Noir and Hong Kong Repertory Theatre in 2011.

[xxv] The play was written by Chan Ping-chiu and co-produced by Hong Kong On & On Theatre Workshop and Taipei’s Mobius Strip Theatre.

[xxvi] Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (London: Sage, 1998), trans. Chris Turner (from La Société de consommation), 25.

[xxvii] Shi Jisheng, “Gei Aofeiliya de shisihang shi [A Sonnet for Ophelia],” Shi tansuo [Poetic Explorations] Feb. 2007: 131-134.

[xxviii] Wu Zhenhuan, “Ophelia,” Sanwenshi 23 (2008): 14-17.

[xxix] The impossibility of the singularity of any category has been examined by Rey Chow’s Woman and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between West and East (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991) and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Spivak, Interview, in Mark Sanders, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Live Theory (London: Continuum, 2006), 121.

[xxx] Ruth Morse, “Reflections in Shakespeare Translation,” Yearbook of English Studies 36.1 (2006): 79-89; del Sapio Garbero (2007: 519-538).

[xxxi] Elaine Showalter, “Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism,” Shakespeare and the Question of Theory, ed. Geoffrey H. Hartman and Patricia Parker (New York: Routledge, 1986), p. 92