Music has always been an important element in Shakespeare’s plays, assisting the audience in understanding the setting of a film, the atmosphere of a scene, or the tone of an entire act. The productions documented on Global Shakespeares display a wide-ranging use of diverse types and styles of music, all intended to enhance the audience’s experience with a play. Listening closely to the music of a production can be as profitable as studying the text, costuming, scenery, and physical acting in a play, and open up new depths of understanding the meaning present in a performance. Here I’ll briefly discuss some of the kinds of music found in works provided by Global Shakespeares, and how they participate in creating what Umberto Eco calls the fictional world of the text.[1] Such listening requires no musical training, only a desire to more fully understand a production through all of the thresholds it gives us as viewers and listeners.

In Po-Shen Lu’s Sonata of the Witches: The Macbeth Verses (/macbeth-unplugged-lu-po-shen-2007/), a 2007 adaptation of Macbeth, a cabaret-style band consisting of piano, winds, and strings is used to establish the surrealism and musical nature of the production. Lu feels that the music is integral to the production; in a 2003 interview, he commented that, “Too much entertainment now is visual. We want people to start listening again.”[2] Of his Unplugged Series, of which Sonata is a part, Lu says that he wants to “return the theater to the actors and actresses, and to focus more on the voice and the body language of the performers rather than on theatrical techniques.”[3]

The production opens with the three witches on stage, singing in counterpoint with one another and the piano in a minor-mode piece whose chant-like aspects signify something(s) quite old. As this changes mode and mood and becomes rather more lighthearted and dance-like, the witches’ attitudes shift as well, suggesting that mischief and chaos, albeit violent mischief, is their end goal. This opening number is based on a four-note motif that will run through all of the music in the play, musically reminding the audience that everything that occurs stems from the witches’ meeting with Macbeth and Banquo at the beginning of the play. It comes back when Macbeth goes to the witches for more prophesying, and as they make him “wash” his hands in the traditional manner of Lady Macbeth. Lady Macbeth “washes” her hands too, but has her own musical motifs that develop over the course of the play. The witches’ music is heard for the last time played on tubular bells—replicating church bells—when MacDuff arrives to kill Macbeth, while the witches watch. The witches return to their earlier, chant-like musical material, staring at Macbeth’s body and finally shrieking with laughter.

Dramatic rolling arpeggios in the piano that also include the witches’ four-note motif enter at the end of Lady Macbeth’s first scene, representing her driving of Macbeth to the killing of Duncan and the instability that her desires and demands will create, not least of which in her own mind. Each time Lady Macbeth pushes Macbeth towards her goals, this rumbling, minor-mode music heightens the atmosphere of danger and evil. It returns, varied, as Lady Macbeth watches Macbeth on his way to the slaying of the King, grasping at a dagger borne by the witches, and again when she expresses her dismay in his behavior after the banquet scene. This music for Lady Macbeth makes a poignant turn when, as she stands alone at the table after the banquet, it first mimics and then uses actual material from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 8, the “Pathetique,” turning the forceful and tyrannical Lady Macbeth into a figure of pity. We hear, though the piano, her descent into anguish and overwhelming pain.

The music for this adaptation of Macbeth tells the audience at once that it is not meant to be realistic or traditional, with singing and dancing witches; nor is it meant to be an adaption that merely transfers the action to a different time or place. It suggests a fantasy on themes of Macbeth, a treatment of the materials of Macbeth without a full staging of the play. The mix of minor and major keys (often heard as “sad” and “happy”) during the witches’ scenes hints that their sense of morality, good, and evil, may not be the same as that of the mortals they affect or the audience who watches them, while Lady Macbeth’s music leaves no doubt that her role is a dramatic and tragic one. The cabaret-style music and small ensemble locates the production in an intimate space—indeed, the stage and cast are small—and the thirteen scenes of the work focus on the relationships in the play. The use of clearly delineated individual music motifs to characterize the witches and Lady Macbeth emphasizes the role of women in the play, and follows their actions and the results thereof through the work.

In Sulayman Al-Bassam’s 2007 Richard III: An Arab Tragedy (/richard-3-al-bassam-sulayman-2007/), two kinds of music are at work. On the Global Shakespeares site, the video is introduced with a sinuous line played by the violin from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, but the music inside of the world of the play is Arabic-style music written by composer Lewis Gibson and performed onstage by an ensemble of Kuwaiti musicians. The arabesque line from Scheherazade promises the audience a fairy-tale-Arabian-Nights-kind of production, full of enchantment and exoticism. The music used in the play itself brings a far more realistic and location-specific aural landscape to its viewers and listeners. As Ben Brantley, reviewing the play in The New York Times wrote, it “has the timeless, propulsive sound of centuries passing to a steady, ominous beat.”[4] The contradiction established in these two musics is made all the more powerful by the play’s score. For Western audiences, the timbral resonances of this music, similar to that used in countless documentaries and news reports about the Middle East, conjures up images of both the past and the present: ancient ruins and modern palaces, camel trails and the luxury cars of the Shah and Saddam, the chaos of unstable, dictatorial governments both old and new. Some of the music locates the play in a modern Arabic country: drumming and electronica are mixed to create musical intros for news bulletins shown over a television screen, and Gibson creates a popular-music based march or rally song for the soldiers who come under Richard’s control and strut on screen, the troops for Richard’s declared “war on terror.” Drumming is also used in a traditional dramatic way to foretell and build tension at moments of crisis—we hear it as the executions of Rivers, Grey, and Hastings approach, and their beheadings are signified with a sharp, sudden “stinger” of loud sounds.

The music does not only set the scene for Al-Bassam’s modern-day Arab Richard, but is also used to underline and emphasize the adaptation’s most dramatic scenes. Edward’s death is announced by sung prayers, cymbals zing when Richard announces a death sentence, and small, high-pitched bells ring at the ends of lamentations by Elizabeth and Margaret. The final battle is accompanied by a rich and multi-textured score that calls to mind the calls of the muezzin and the sounds of modern warfare together, the sounds of an Arab tragedy.

Other plays and films on the Global Shakespeares site offer numerous other musical materials that locate the productions, create a tone for the direction of the play, help identify characters as themselves and in disguise, and add to the verisimilitude of the fictional worlds the performances create. The opening scene of Yukio Ninagawa’s 1985 Macbeth (/ninagawa-macbeth-dir-yukio-ninagawa-1985/#clip=1) combines the sounds of Buddhist gongs with the ethereal sound of French composer Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem, creating an atmosphere of concommitant mourning and peace that, as Alexander Huang comments on the production’s main page (see also his chapter on Ninagawa in The Great Shakespeareans vol. 18), “compels the audience to dwell upon memories of the dead and the fault line between the sacred and the secular.” The same production uses Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings during the final fight between Macbeth and MacDuff (/ninagawa-macbeth-dir-yukio-ninagawa-1985/#clip=6), again musically referencing death by way of Barber’s work, which was played at the funerals of Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, and has been used in countless films and television shows to signify tragedy.

Patrick Doyle’s art-music, quasi-Italianate score. Much Ado About Nothing, dir. Kenneth Branagh (1993)

Patrick Doyle’s art-music, quasi-Italianate score for Much Ado About Nothing (/much-ado-branagh-kenneth-1993/) uses memorable melodies that accompany the film from start to finish, suggesting through its major and minor key variations the emotions and tenor of each scene. In this clip, we hear the light dance music of the revelers turn dark and foreboding as Don John’s men seek to trick Claudio for the first time, identifying Don John as the villain and creator of unhappiness amongst the otherwise merry festivities.

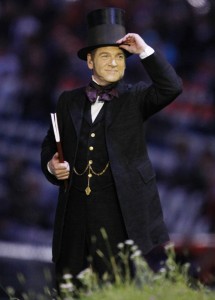

As a final example, Danny Boyle’s Closing Ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London (/2012-london-olympics/) connected Shakespeare musically through two of the country’s best-known piece of musics: the hymn “Jerusalem” (0:00-0:37) which has stood to represent Britain in everything from Monty Python’s Flying Circus to military memorials; and Edward Elgar’s “Nimrod” from the Enigma Variations (0:50-2:03), a work which is played at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday and has been used to signify the British Isles and character in films such as Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth.

Kenneth Branagh dressed as Isambard Kingdom Brunel and reciting Caliban’s speech at the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics

Even without knowing the names or backgrounds of these pieces of music, audiences can understand the flavor and mood of each piece, what they convey in terms of their connections with a particular scene or character, and how they enhance a production. Close listening—for character, style, and even the instruments used—can add worlds to the understanding of a performance, and takes away nothing. When Hamlet asks, “Will the King hear this work?,” he speaks not just to the text, but to the music that accompanies, surrounds, and supports it, all part of the whole.

——————————————

About the Author

Kendra Leonard is a musicologist whose work focuses on women and music in twentieth century America, France and Britain; music and screen history; and music and disability. Her current research projects are on American composer Louise Talma and music and the English early modern period on screen. Her book Louise Talma: A Life in Composition will be published by Ashgate Publishing in 2014. She is the Director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive (SFSMA.org). She is the author of The Conservatoire Américain: a History and Shakespeare, Madness, and Music: Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations.

More at Dr. Kendra Leonard’s website

[1] Umberto Eco, Confessions of a Young Novelist (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011), 81.

[2] Ian Bartholowmew, “Tainan Jen gets Macbeth talking,” Taipei Times, May 23, 2003. Accessed at http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2003/05/23/2003052339.

[3] Hermia Lin, “In Shakespeare we love and play—Tainaner Ensemble,” culture.tw, March 31, 2009. Accessed at http://www.culture.tw/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1189&Itemid=157.

[4] Ben Brantley, “Gloucester’s Emir, Handsome This Time,” The New York Times, June 11, 2009. Accessed at http://theater.nytimes.com/2009/06/11/theater/reviews/11brantley.html?_r=0.