TNT theatre are currently on tour in China with Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Paul Stebbings reflects on their experience touring Shakespeare productions in China.

Last week we drove into a sprawling boom city larger than Rome or Berlin. Our first performance was at a new university campus miles from the centre in an industrial zone that was thankfully obscured by smog. At the city limits we were greeted by a new construction: a semi circle of vast Doric columns linked by classical arches and reminding me of a recent visit to the Temple of Zeus in Athens. The backdrop was a clutter of tower blocks, pylons and smoke stacks. Later that same day well over one thousand students packed into a lecture theatre to see our performance, many stood for almost three hours and even the stairs were used as seats. It would be impossible to ask for a better audience. They laughed and shouted their approval, interrupting the Mechanicals scenes with constant applause and cheering when the lovers were finally reunited to their true loves. There was no irony in their response which was entirely fresh, one felt transported to the Globe on the play’s first night. One woman told me that she had never been to live theatre before, let alone a Shakespeare play in its original language. So the question is: what is the relation between the complete misunderstanding and misuse of Western classical culture that the columned monument represents, and the astonishing passion for what one would like to think is genuine classical art: Shakespeare’s MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM? And how can these two responses co-exist in such proximity?

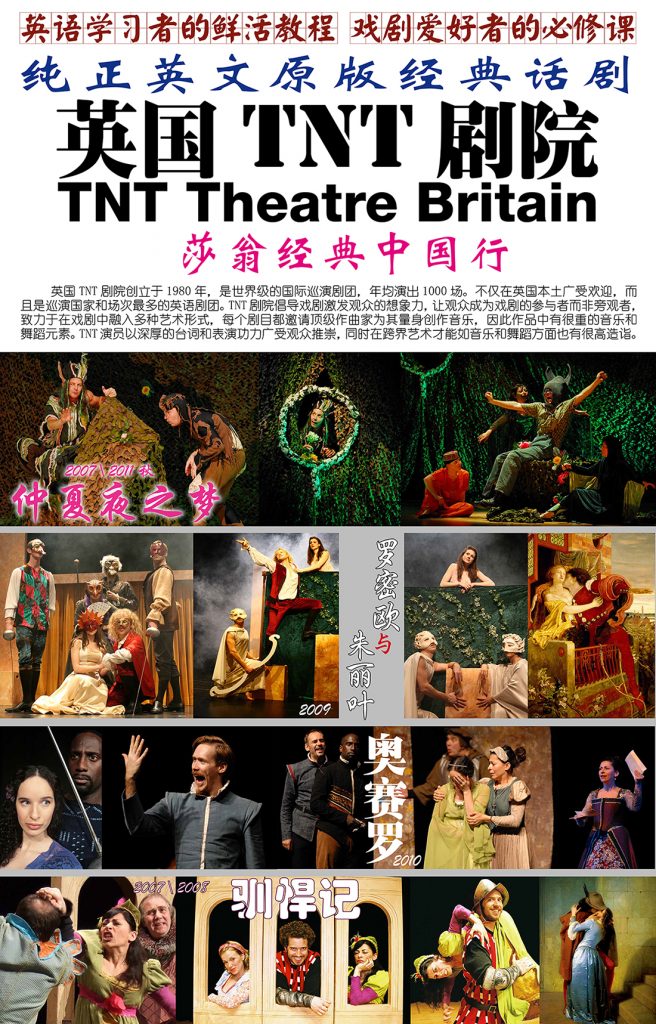

I started off by asking a Chinese friend why they thought the columns were built and why if a monument was needed to somehow relate to a classical past that there was not a Chinese monument reconstructed at the entrance to the suburb. He replied that “the Chinese lack self-confidence.” This may seem strange given the extraordinary achievements of modern China in every field from economics to athletics but I would suggest it means that modern China is often more satisfied with its present and its future than it is with its past. Dislocation is for me a key word when trying to relate to China today. I offer another example: in Shanghai there is a fascinating private museum of Maoist posters and propaganda paintings. There is nothing critical of the Communist party and although the museum is in the basement of an apartment building it is clearly not clandestine, you can find directions to it in the Lonely Planet guide. Much of the art work is exceptional, and its historical value is immense. When I told a different Chinese friend about this museum, a young artist who is bilingual and well travelled, he said: “ What do you want to go there for? No one is interested in that old stuff any more.” So I propose that if this “world is out of joint” Shakespeare offers a response that strikes a chord, a way of dealing with cultural dislocation. How else can we describe the status of Shakespeare in China, where for example, four thousand people came to see TNT’S OTHELLO in a medium size city near Guangzhou, crowding into an outdoor arena as if at rock concert. And this is not a general desire to see Western performance. We have on occasion struggled to raise an audience, for example for our highly accessible stage version of GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (the real thing not just Lilliput for kids). Having filled the National Centre for Performing Arts in Beijing for ROMEO AND JULIET we were disappointed to see half empty houses at the same theatre one week later for GULLIVER. Our producers, the excellent Milky Way Arts company, have decided that Shakespeare is the only way forward for our national touring (with the possible exception of one or two Dickens titles). TNT’s sequence of Shakespeare productions in China has been: MACBETH (twice), TAMING OF THE SHREW (twice), A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM (twice), HAMLET, ROMEO AND JULIET, OTHELLO and MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING. Last year I directed a new version of TAMING OF THE SHREW in Mandarin at Shanghai’s leading theatre, the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre. The production sold out and is currently being revived.

TNT are based in Britain and Germany and perform Shakespeare’s works (and many other plays) worldwide, but I propose that the position of Shakespeare in China is exceptional. The only parallel is Germany, where a similarly dislocated society has embraced Shakespeare with a passion and freshness approach that puts Britain to shame. But the German experience of Shakespeare began a long time ago, what is fascinating about China is that the first translation of a Shakespeare play into Mandarin was less than a hundred years ago, and that we can witness the astonishing rise of Shakespeare to the status of core writer in a culture that is so ancient and successful yet ambiguous about its rapid rise. “And nothing is but what is not…”.

China is unique in that it underwent a Cultural Revolution, a phrase so well known that it is in danger of losing its original meaning. This ancient civilisation experienced a total break with its past, a cutting off of its cultural lifeblood, and all within the lifetime of many Chinese. The connection is regrowing but the trauma remains. How similar this is to the savage break with the past that Shakespeare experienced within his lifetime. The Reformation smashed not only the continuity of religion but of theatre, the Catholic mystery plays were destroyed forever. Shakespeare’s fear of civil war and chaos, an ever present theme from HENRY THE SIXTH to the TEMPEST, is a Chinese preoccupation as they look back on the period from the Opium wars to the fall of Madam Mao. The cultural dislocation of Elizabethan England was the background and starting point for Shakespeare’s revolutionary idea: that the individual could explore the answers to the conundrums of the age without recourse to fixed beliefs. As Hamlet points out “There is nothing good nor bad but thinking makes it so”. Shakespeare defines the modern individual consciousness, expresses it with greater clarity than most philosophers or religious thinkers and does so in a form that is accessible to almost anyone. There were many Chinese children in our (subtitled) performance of DREAM last night in Beijing. They were held to the very end, howling with delight when Titania fell in love with the ass or Pyramus over acted his suicide. Beyond the entertainment offered by Shakespeare’s stories and characters (and it was Lamb’s TALES FROM SHAKESPEARE that first made an impact in China according to Professor Huang) , Shakespeare is gloriously incomplete and wonderfully unspecific. Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling is a work on a par with KING LEAR, but it is first of all finished and secondly requires an understanding of Catholic mythology. KING LEAR is set in an invented Albion that has more in common with China in 1900 than modern Britain. How often in the first half of the twentieth century did the typical Chinese feel that they were as flies to wanton boys, that the gods killed them for their sport? And what gods? Fill in as you wish. While a dying and betrayed Sun Yat Sen (founder of modern China) is closer to King Lear than any British politician I can think of. I set my Mandarin version of TAMING OF THE SHREW in 1930’s Shanghai. Baptista’s family (including Kate) were dressed in conservative traditional costume, Petruchio in a flash European suit. Jazz music clashed with traditional songs. The production not only made sense (I hope!) but expanded its meaning in a way that a 1930’s English setting would have been what I loathe: historical set dressing as a substitute for thoughtful direction.

Thoughtful writing has not been as divided in China as it has in Europe between art and philosophy. From Confucius and Mencius to Mao’s own poetry, there is long tradition of the artist as a guide to living. “To be or not to be” is quoted to me with such regularity as I travel China that it clearly means something special to modern, educated Chinese. HAMLET grips the Chinese imagination , this most dislocated of Shakespeare’s creations holds up a special mirror to the Chinese soul. In Shakespeare all is shifting and uncertain, love, power and life itself is provisional and uncertain. The world is built on sand, man being Hamlet’s “quintessence of dust”. Dust on sand. Only extreme life affirming action can stand against this shifting tide. Hence the massive popularity of ROMEO AND JULIET (our best visited play nationwide). And let us not forget the comedies, whose profundity operates in an equal but different plane. The comedies seem to promise that extreme commitment to love and all its apparent foolishness can result in happiness. In a China of fractured families and single children, true love is the one relationship that holds promise. It is worth anything and everything or perhaps it is much ado about nothing.

I do not pretend to be an expert on China. But I do experience the extraordinary impact of Shakespeare on modern China. The upheavals of the twentieth century are past, but Shakespeare also offers an antidote to the tawdry globalisation and fake classicism that sweeps across East Asia. Perhaps he also offers a moral compass on turbulent seas. While in an over digital world he also promises a good night out: live theatre shared with other people. It’s a potent mix.

Paul Stebbings

TNT theatre UK

paul@tnt-theatre.net