About This Clip

Twelfth Night

Pavel Safonov’s production of Twelfth Night at the Moscow Academic Theatre of Satire (premiere in 2017) is a compelling spectacle that openly rejects the long-standing Soviet tradition of reading the play through the lens of socialist realist ideologies.

Cast and Crew

Director: Pavel Safonov

Stage design: Marius Iatsovskis

Costume design: Evgeniia Panfilova

Music composer: Faustas Latenas

Choreography: Alisher Khasanov

Stage manager: Natalia Aleksandrova

Actors:

Orsino – Andrei Barilo

Sebastian – Sergei Beliaev

Antonio – Anton Buglak

Captain – Anton Buglak

Orsino’s courtiers – Veronika Agapova, Marina Maniakhina, Arina Kirsanova

Sir Toby Belch – Igor Lagutin

Sir Andrew Aguecheek – Sergei Kolpovskii

Malvolio – Mikhail Vladimirov

Feste – Oleg Kassin

Olivia – Liana Ermakova

Viola – Elena Tashaeva

Maria – Svetlana Maliukova, Liubov’ Kozii

Twelfth Night soundtrack excerpt – music by Faustas Latenas

Curated by Dr. Natalia Khomenko, York University, Canada

Feste, Sir Toby, and Sir Andrew

“Wise Enough to Play the Fool”: Pavel Safonov’s Twelfth Night at the Moscow Academic Theatre of Satire

Introduction

Pavel Safonov’s production of Twelfth Night at the Moscow Academic Theatre of Satire (premiere in 2017) is a compelling spectacle that openly rejects the long-standing Soviet tradition of reading the play through the lens of socialist realist ideologies. Rather than approaching Twelfth Night as a “realistic” representation of early modern class tensions, this production ultimately collapses all power hierarchies and stages a carnival of fools and clowns that leaves no character outside of its celebration, and its gentle mockery.

Soviet Russia had had a long and intimate involvement with Twelfth Night, often viewing it as a consummate example of Shakespeare’s Renaissance humanism. Beginning with the 1930s, Soviet critics and directors emphasized the play’s inclusion of lower-class characters (as represented by the captain, Antonio, Maria, and Feste), who were interpreted as the vehicles of earthy folk wisdom, salty humour, and all-conquering optimism. The play’s focus on intense romantic love allowed for it to be interpreted, by Soviet scholars and directors, as a didactic tale of individual emotion triumphing over the stultifying restraints of feudal ties, social hierarchies, and religious doctrine (the last, of course, represented by Malvolio). The Soviet era therefore treated the play as a “serious” work that deserved to be staged “realistically” – i.e. with close attention to historical accuracy.

Safonov’s production defiantly unmoors itself from any particular place or time and emerges, phoenix-like, from the debris of past interpretative traditions, signalled by the pieces of broken statuary strewn across the stage for the duration of the play.[1] This production does not attempt to generate an internally consistent reading of Twelfth Night. Instead, it introduces a wild variety of visual references, with an occasional clown routine or chunks of new text inserted along the way. Effectively, the carnivalesque space created by Safonov’s approach to Twelfth Night invites contemporary Russian audiences to interrogate the view, inherited from the Soviet era, that Shakespearean drama must be at all times treated as serious, sustained social commentary and be carefully preserved as such on stage. Tracing some of the innovative staging choices in this production, my review examines its emphasis on the all-healing, unifying power of spectacle, and its underlying argument for updating Shakespearean text for contemporary audiences.

Performance and Carnival

The Theatre of Satire production opens with a vision of Orsino and Olivia trapped by their own positions of power, and by their social performances of emotional excess. The ways in which Orsino and Olivia choose to present themselves to the world are closely examined and mercilessly burlesqued. When we first see Orsino, he is wearing all black, as befits a heart-sick lover – attractively unshaven, clad in a long coat, with bare ankles visible between trousers and polished shoes. He also has several passably realistic doves affixed to his coat and his head. It is not until his second appearance, when he begins removing the doves, that we notice the bird droppings staining his coat. The accoutrements of romantic love, when examined closely, reveal a performance that is unfailingly hilarious in its self-conscious hyperbole. Orsino’s retinue of three women seem entirely used to his exaggerated love melancholy, dutifully providing the punch lines to his opening speech and, at their master’s request, playing up to his highly stylized suicide attempts. There are two such attempts in the course of the play: in the first scene, the Duke goes as far as to put his head through the noose hanging from a portable gallows, and later sets a gun to his temple. In both cases, the retinue’s main concerns are with supplying the implements, providing a drumroll accompaniment, and taking a group selfie beforehand, suggesting that this is a well-worn and well-loved game practised by the household. Indeed, the retinue greets Viola-as-Cesario’s success in cheering up the Duke and gaining admission to Olivia with narrow-eyed suspicion and displeasure, obviously put out by this disruption of the melancholy lover routine.

This production’s look at Olivia’s excess of grief and her later passion for Viola-as-Cesario is just as unflinchingly comical – and poignant, presenting her as a woman closely held by the routines and expectations of her court. In her first appearance, Olivia is wheeled onto the stage by Maria and Malvolio (probably on the same platform recently used for the gallows), elaborately gowned and veiled, in a posture of frozen grief. Maria, with her dark glasses, rigidly set hair, and a neat travelling outfit, as well as Malvolio in an understated yet tasteful grey suit with the broad band of pink cloth wrapped tightly around his chest, resemble nothing so much as dignitaries of some unspecified police state. This impression is intensified by the fact that both Maria and Malvolio are involved in their ruler’s demonstrative performance of distracted grief: all three enter wailing and sobbing into their handkerchiefs. Periodically, Malvolio whips out a box of powder and fussily repairs the façade of Olivia’s face to ensure the best presentation. Presenting Olivia’s mourning and seclusion as a piece of political theatre, the production also offers an explanation for her sudden passion for Viola-as-Cesario. As an outsider to this political performance, Viola is able to see beyond the inventory of beautiful parts (“item, two lips, indifferent red”),[2]which Olivia delivers in a circus barker’s voice, each item accompanied with a drumroll. After this clearly rehearsed inventory has been delivered, and the two are sitting on the stage silently side by side, Viola reaches out to take Olivia’s hand and diligently works to warm it up, rubbing and breathing on the skin, re-enacting a metaphor of awakening a beautiful statue.

In the course of the production, both Orsino and Olivia move (she rapidly, he grudgingly) from clinging to the scripted performances that make them, ultimately, foolish – as the Fool’s remarks make abundantly clear – to embracing unfettered, carnivalesque physicality. This transformation is staged beautifully, and hilariously, in Olivia’s garden, with Sebastian wondering whether this can all be a dream, and whether the lady of the house might be mad. Here, Olivia, disheveled by passion, her hair loose, writhes voluptuously on the stage during his speech, even as Sebastian comments on her management of the household affairs and praises her “smooth, discreet and stable bearing,”[3]all the whole glancing nervously at the lady’s undulating body.

Sir Toby, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, and Feste, all wearing white face paint and stylized costumes, embody the carnival spirit of Safonov’s production. Together, they form a clown team whose rambunctious physical routines emphasize the intense theatricality of this stage version. Sir Andrew, one of the potential scapegoats in Twelfth Night, never invokes the audience’s pity. His affections, easily swinging from one woman to another, are presented as a buffoonish parody of the main characters’ intense concern with performing love. Tall, curly-haired, with his red trilby and stockings, riding a gigantic red circus tricycle, Andrew is a modern take on the figure of country bumpkin, in contrast to the wryly sophisticated Toby dressed in black-and-white costumes. The clown team is eventually joined by Maria, who starts out as a relatively conventional servant, as per the play text. However, having decided to take her revenge on Malvolio, she joins the carnival as a somewhat sexualized Columbina – wild hair, ragged skirt (a couple of times, during particularly strenuous leaps, the audience is treated to glimpses of her underwear), high-heeled boots, and – occasionally – a red clown nose.

More than any other character, Feste serves to highlight the theatricality of this production, and its cheerful disavowal of any weighty didactic import. His first appearance on stage, before the initial encounter with Sir Toby and company, is the case in point. Feste enters alone and treats the audience to a circus skit involving a trapdoor with a mysterious entity presumably hiding under the stage. At one point in the skit, Feste, with exaggerated effort, drags a kettlebell to the trapdoor and drops it in. Just as he assumes a pleased expression (ha! that fixed him!), what seems to be the same kettlebell unexpectedly drops from the ceiling backstage. This kind of interaction is not unusual in a circus skit, where a clown typically attempts various approaches to subdue entities or objects that defy him. But suggesting a mind-boggling looping of space, with the “down” of the trapdoor inexplicably leading to the ceiling, presents the audience with a beautiful physical manifestation of the topsy-turvy comedy world, seemingly free from the rules and limitations of the real world.

Moreover, Feste’s own social persona is eventually revealed to be similarly unstable; in the carnivalesque space of this production, normal class boundaries are suspended, and the clown moves with ease from one role to another. This is most clearly demonstrated by the new materiality taken on by Feste’s Father Topas disguise. In the play, this disguise is briefly constructed for the purpose of tricking Malvolio, but in Safonov’s production it reappears in Act 5, scene 1, in the first direct confrontation between Orsino and Olivia. The audience is not shown the wedding ceremony between Olivia and Sebastian, but when the exasperated Olivia summons the priest who had officiated it, it turns out to be none other than Feste, still dressed as Father Topas. Lest we assume that the actor is simply doubling up for a bit part, Feste, as Orsino flips him a coin for the information, smugly comments, “I told you, the third pays for all” [ia zhe govoril, tri – luchshe, chem dva].[4]This, of course, is a direct reference to their exchange earlier in the same scene, with Feste the Fool doing his best to finagle more coins from the Count.[5]Orsino’s startled look testifies that this exchange is still fresh in his memory, and that he is as surprised as the audience by Feste’s new persona. If, within the logic of the play, Olivia and Sebastian are in fact married, this moment blurs the line between Feste’s “real” social status and power and his temporary disguise, arguing that an assumed disguise, even when recognized as such, can have its own indubitable reality.

Following this idea to its logical conclusion, the production ultimately collapses all social hierarchies of the play and culminates in a levelling celebration that leaves no one out in the cold, even Malvolio, the usual scapegoat of Twelfth Night. After receiving the forged letter, Malvolio has shucked off the initial state dignitary persona, and appears in a tutu, yellow tights, and ballet slippers, now also with his face clownishly white.[6]He is, even then, well on his way to joining the rest of the clowns, and it is difficult not to sympathize with his mournful distress in the dungeon. Although Malvolio does deliver his famous line, swears to be revenged “on the whole pack” of them, and walks away from the others, he remains on the stage, practising ballet poses while the conclusion unfolds. At the end of the play, he happily rejoins the community, and his yellow stockings blend in perfectly with the rest of the clown outfits. To enable this seamless reintegration, the production also excises Feste’s concluding song – this reminder of rainy weather, passage of time, and potential loneliness. Instead, the play ends with a slow fade-out, as all characters, grouped toward the back of the stage, throw roses that, sticking upright, magically create a flower garden in the middle of the stage – an illusion that their communal, carnivalesque happiness can be at least temporarily preserved from the relentless pressure of the real world.

Shakespeare’s Text in Post-Soviet Russia

Having explicitly abandoned the Soviet tradition of staging Twelfth Night as a historically accurate depiction of the Renaissance social structures, Safonov’s production encourages the audience to consider the problem of approaching Shakespearean text after the dissolution of rigid socialist realist ideological policies. Where Soviet theatre insisted on its ability to recover the “authentic” Shakespearean drama, the post-Soviet stage must recognize that its encounter with Shakespeare’s plays, mediated by translation and cultural distance, requires a constant reinvention of the text. The Theatre of Satire highlights this process of reinvention by supplementing Andrei Kroneberg’s somewhat dated 1841 translation[7] with lines and whole dialogues in contemporary idiom, to great comic effect. The production’s treatment of Feste’s singing interludes, in particular, invites an interrogation of the ways in which Shakespearean text must be re-constructed and revised for the post-Soviet audience.

Consider, for example, the moment when Feste is invited to sing for the first time in Shakespeare’s play. In response to Toby and Andrew’s request for “a love-song,” Shakespeare’s Feste performs “O mistress mine,” which has withstood the test of time reasonably well and enjoyed some modest popularity along the way in the English-speaking world.[8] The same, unfortunately, cannot be said for Kroneberg’s translation of this song in Russia. In a stroke of brilliance, Safonov’s production has Feste sing the Beatles’ “Michelle ma belle” instead. This choice is less random than it might seem to a Westerner. In the 1970s, as the youth of late Soviet Russia would have happily sold out Lenin’s revered corpse for some western fashions or music, the Beatles were a band widely known on this side of the Iron Curtain. Occasionally, they were advertised as working-class boys whose songs (with the help of some creative translation) supposedly challenged capitalist mores.[9] In other cases, their songs were released as “folk” music. The Beatles were the young people’s version of Shakespeare – a foreign transplant, carefully shaped to fit the ideological requirements of Soviet Russia, but nonetheless serving as a connection to other countries and languages, and potentially subversive.[10] “Michelle ma belle,” with its re-enactment of linguistic confusion and longing for the seductive cultural other, a song utterly familiar to the post-Soviet audience, becomes a striking illustration for Russian Shakespeare as not fully comprehensible yet intimately claimable – and infinitely flexible – construct.

The ongoing negotiation of Shakespearean text in post-Soviet theatre becomes even more explicit when Feste is asked by Orsino to sing “the song we had last night.”[11] “Michelle, my belle?” he tries tentatively, but the Duke shakes his head – no. After some short pondering, we see a lightbulb go on: Feste now seems to understand what is required of him, and goes on to perform Kronenberg’s translation of “Come away, come away, death.”[12]In contrast to the frivolity of the Beatles’ lyrics on Feste’s lips, this song is appropriately mournful and – as the audience might assume – more suited to Shakespeare’s play. But as the last sad note dies away, Orsino, who has been listening with a rapt face, now announces gravely: “This is [pause] not the right song” [Eto… ne ta pesnia]. The audience greeted his anticlimactic pronouncement with general laughter, but for those who are conversant with the text it presents an interesting paradox. The song that is more “authentic” (i.e. can be traced back to Shakespeare’s play) is rejected by the play’s character as not “right” for a production that seeks to evoke laughter in a contemporary Russian-speaking audience.

Conclusion

I went to see Safonov’s production of Twelfth Night at the Theatre of Satire while in Moscow for a research trip in the summer of 2018. Unusually for me, I was accompanied by two women who had never read a Shakespeare play or experienced one on stage: my Airbnb hostess (a classical musician) and my cousin (an aircraft engineer). Needless to say, I was apprehensive about their potential reaction, especially when discovering that the production was using a nineteenth-century translation and would run for three and a half hours. My cousin confessed, as we were taking our seats, that she had attempted to read through a synopsis of Twelfth Night in advance, but was quickly confused and exasperated by the multiple, intertwining plot lines. Theatre, she added morosely, was not her thing.

But both of my companions were almost immediately entranced and utterly delighted by the performance. While I could see that the somewhat cumbersome language of Kroneberg’s translation lost them at times (much as might happen to a Western audience dealing with Shakespeare’s early modern text), the production always recaptured their attention by offering a contemporary reference, or witty visual commentary on archaic poetic and social convention – such as the unappetizing droppings left by Orsino’s romantic-lover doves on his coat. The carnival atmosphere of this Twelfth Night, and the brave insistence on a happy ending for all, albeit as fragile as artificial roses growing from the stage, drew even these two somewhat reluctant women into its celebration.

Perhaps expectedly, some reviewers were dissatisfied precisely with Safonov’s refusal to treat Shakespeare “seriously,” and with his failure to stage this play as a scathing critique of social vices. One review, published electronically immediately after the premiere, began by stating that only fools can view Twelfth Night as a source of merriment. The review cited Auden’s opinion on the play (nothing to laugh about), and informed the reader that this is one of Shakespeare’s “most difficult-to-understand works” and one of his “bleakest” [samykh mrachnykh] plays.[13] Here is, then, the value of Safonov’s production: that, in the post-Soviet context, where the view of Shakespearean drama as weighty and grim continues to persist, it sets its sights on celebrating Shakespeare’s comedy, with its sheer potential for spectacle and verbal hilarity. In that, as my experience in the theatre witnesses, the production succeeds beautifully.

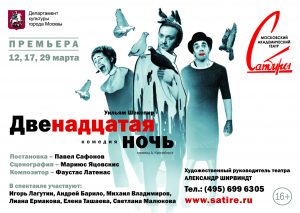

Poster of Twelfth Night

Sir Toby and Andrew Aguecheek

Olivia and Orsino

Olivia and Sebastian

Olivia

Malvolio

Left to right: Toby, Maria, Orsino (behind Maria), Feste, one of the officers, and Antonio (cut in half)

The entire cast of the play at the back of the stage, after the last words of the play have been spoken (the stage is deliberately darkened at this moment, so most faces cannot be seen clearly).

[1]It is perhaps useful to mention here that the Moscow Academic Theatre of Satire was founded in 1924 as part of the early Soviet culture-building, which means that its existence spans almost the entire Soviet era.

[2]William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, or What You Will, ed. Roger Warren and Stanley Wells (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 1.5.235. All further references are to this edition.

[5]Feste says to Orsino, “Primo, secondo, tertiois a good play, and the old saying is ‘The third pays for all’. The triplex, sir, is a good tripping measure, or the bells of Saint Bennet, sir, may put you in the mind – ‘one, two, three’” (5.1.32-35).

[6]Whether or not this is deliberate, in his mad lover persona – grinning and assuming ballet poses – Malvolio has an uncanny resemblance to Jeremy Hillary Boob, PhD, the Nowhere Man character in the Beatles’ 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine.

[7]This choice of a translation is a curious one, although perhaps informed as much by copyright issues as by its objective merits. Laurence Senelick dismissively calls Kroneberg’s translation “stilted” when discussing its use in the early post-revolutionary years. See Senelick, “Brief Encounters: Michael Chekhov and Shakespeare,” in The Routledge Companion to Michael Chekhov, ed. Marie Christine Autant Mathieu and Yana Meerzon (London/New York: Routledge, 2015), 141-160. Nonetheless, in practice this choice proves a success. Some of Kroneberg’s now-archaic phrases are even emphasized for comic effect, especially in Orsino’s scenes, pointing to the rather artificial and unwieldly nature of his passion.

[8]Twelfth Night, 2.3.37-50. For example, this song echoes throughout Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of the Hill House(1959), as lines from it keep recurring to the protagonist Eleanor.

[9]As an inquiring teenager going through my father’s accumulation of old papers (which occasionally yielded dusty and endlessly fascinating samizdat), I once found a script obviously intended for some university student party where, daringly, some songs by the Beatles would be played. According to the script, before each song the Soviet equivalent of a DJ would read out a short “summary,” which also commented on the ideological significance of the piece. Although the script has long been lost to the ravages of time, I still have a vivid memory of the introduction intended for “Baby, You Can Drive My Car.” The introduction explained that in a capitalist society all possessions are highly prized and jealously guarded, and the singer’s willingness to let his girlfriend drive his car is nothing less than revolutionary, demonstrating the band members’ rejection of their money-oriented world. It didn’t quite say that The Beatles were communist sympathizers, but the implication was there. (I mean, they did have that song about coming back to USSR, after all.)

[10]For extensive – if somewhat impressionistic and embroidered – commentary on the Beatles’ role in destabilizing late Soviet ideologies, see Leslie Woodhouse, How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin(Bloomsbury, 2013).

[13]Alla Mironenko, “ ‘Dvenadtsataia noch’’ stala tsirkovoi” [Twelfth Night turned into circus], Revizor: Informatsionnyi internet-portal o kul’ure v Rossii i za rubezhom, published March 15, 2017, accessed September 24, 2018, http://www.rewizor.ru/theatre/catalog/teatr-satiry/dvenadtsataya-noch/retsenzii/dvenadtsataya-noch-stala-tsirkovoy/. This informational website is an officially registered cultural news resource, and is partly supported by a President of the Russian Federation grant.

Related Productions

- Nata e Dymbëdhjetë (Twelfth Night) (Anderson, Justin; 2018)

- Noche de Reyes (Twelfth Night) (Azurmendi, Jorge; 2011)

- The Speaker’s Progress (Twelfth Night) (Al-Bassam, Sulayman; 2011)

- Twelfth Night (Bow Shakespeare Series #4) (Kimura, Shinji; 1999)

- Twelfth Night (Digital Stage series) (Çı̇çek, İbrahı̇m; 2021)