Prologue: the making of a Fool (0:01:48)

Prologue: the making of a Fool (0:01:48)

Fool’s song (0:00:36)

Fool’s song (0:00:36)

Fool’s perspective (0:00:54)

Fool’s perspective (0:00:54)

Lear’s entry with fanfare (0:02:13)

Lear’s entry with fanfare (0:02:13)

Lear narrates his intent (0:00:49)

Lear narrates his intent (0:00:49)

Goneril and Regan are heralded (0:00:23)

Goneril and Regan are heralded (0:00:23)

Cordelia enters separately (0:00:07)

Cordelia enters separately (0:00:07)

Lear’s announcement of the love-test (0:00:45)

Lear’s announcement of the love-test (0:00:45)

Goneril speaks and is rewarded (0:01:16)

Goneril speaks and is rewarded (0:01:16)

Regan weeps and is rewarded too (0:00:59)

Regan weeps and is rewarded too (0:00:59)

Cordelia’s “nothing” (00:00:18)

Cordelia’s “nothing” (00:00:18)

Cordelia’s political protest (0:00:22)

Cordelia’s political protest (0:00:22)

Goneril and Regan rebuke Cordelia (0:00:06)

Goneril and Regan rebuke Cordelia (0:00:06)

Kent intervenes and is banished (0:00:56)

Kent intervenes and is banished (0:00:56)

Cordelia’s final statement and her banishment (0:00:50)

Cordelia’s final statement and her banishment (0:00:50)

The elder sisters corner Cordelia (0:00:39)

The elder sisters corner Cordelia (0:00:39)

Fool’s satirical Interlude (0:01:06)

Fool’s satirical Interlude (0:01:06)

Fool introduces the subplot (0:00:32)

Fool introduces the subplot (0:00:32)

Lear’s second entry (0:01:34)

Lear’s second entry (0:01:34)

Oswald and Kent (0:00:49)

Oswald and Kent (0:00:49)

Goneril, Oswald and Lear (0:00:28)

Goneril, Oswald and Lear (0:00:28)

Goneril chastises Lear (0:00:43)

Goneril chastises Lear (0:00:43)

Goneril’s soliloquy (0:00:15)

Goneril’s soliloquy (0:00:15)

Lear’s third entry, with fanfare and song (0:00:49)

Lear’s third entry, with fanfare and song (0:00:49)

Fracas outside Regan’s palace (0:01:16)

Fracas outside Regan’s palace (0:01:16)

Kent is released (0:01:27)

Kent is released (0:01:27)

Regan tries to reason with Lear (0:01:04)

Regan tries to reason with Lear (0:01:04)

Lear’s dirge-like grief at rejection (0:00:54)

Lear’s dirge-like grief at rejection (0:00:54)

Lear pleads with folded hands (0:00:56)

Lear pleads with folded hands (0:00:56)

Lear’s ultimate abjection: lies down on his body cloth (0:01:03)

Lear’s ultimate abjection: lies down on his body cloth (0:01:03)

Lear’s madness (00:01:07)

Lear’s madness (00:01:07)

Gloucester upbraids the sisters (0:01:13)

Gloucester upbraids the sisters (0:01:13)

Storm breaks and Lear curses the world (0:01:57)

Storm breaks and Lear curses the world (0:01:57)

Cordelia comes to rescue Lear (0:01:30)

Cordelia comes to rescue Lear (0:01:30)

Fool’s last words (0:01:54)

Fool’s last words (0:01:54)

About This Clip

Iruthiattam

Iruthiattam, a 2001 Tamil-language adaptation of King Lear. The production was directed by R. Raju from a script by Indira Parthasarthy.

Read more about the “indigenised Shakespeare” performance style.

Video of performance took place on 27 Feb. 2001 at the Nataka Bharathi 2001 Shakespeare on Indian Stage, national theatre festival and seminar at Kasargode, Kerala, India, 24 Feb – 2 March 2001, in association with the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi.

Iruthiattam

Clips

Fool’s last words

The play ends with the voice of the Fool plaintively calling out for, searching for, Lear, “Tatta, Tatta…” / Grandfather. The Fool is given the last word in keeping with...more

The play ends with the voice of the Fool plaintively calling out for, searching for, Lear, “Tatta, Tatta…” / Grandfather. The Fool is given the last word in keeping with his role as sutradhara or choric commentator, underlining the central paradox of the play: “The King said – do you remember (to the audience)? – I was his other half? Whe you are the Fool, you know the intelligent / knowing ones are fools. Then who is the wise one? Me. There is no competition, no quarrel, no fight for my position / title.”

The Fool is left carrying Lear’s wrap and staff – symbols of power – of which Lear has at last been divested. He continues to call for him, not knowing that Lear has been taken away by Cordelia. The play closes on an elegiac note, memorializing the sufferings caused by the failure to understand oneself. less

Lear pleads with folded hands

Goneril arrives on the scene and upbraids Lear for his highhanded behaviour. Cornwall and Regan too add their bit. Lear pleads / begs, in a most poignant manner, with folded...more

Goneril arrives on the scene and upbraids Lear for his highhanded behaviour. Cornwall and Regan too add their bit. Lear pleads / begs, in a most poignant manner, with folded hands, a posture usually adopted when speaking to the elders or to someone in authority by the lowly. The sisters remain unmoved, driving him to seek consolation in the embrace of his remaining followers, Kent and the Fool. less

Lear’s ultimate abjection: lies down on his body cloth

In a gesture of ultimate abjection, Lear spreads his angavastam / body-cloth (the long scarf on the shoulder), a symbol of honour, which was usually worn by the elite, on...more

In a gesture of ultimate abjection, Lear spreads his angavastam / body-cloth (the long scarf on the shoulder), a symbol of honour, which was usually worn by the elite, on the floor. This showed his complete humiliation, a giving up of his self-respect in which he is reduced to the lowest level. He lays himself down on it, to emphasize his helplessness and begs the daughters for shelter and support, addressing them as “Tai” / Mother. When he receives the daughters’ hauteur in return: Regan “You have fought with her, I cannot take you back,” and Goneril: “Three months here, three there, without your retinue,” something gives up within him and he petitions the Gods for patience. less

Gloucester upbraids the sisters

Loyal Gloucester upbraids the sisters for their mistreatment of their father, “Stop him, it’s your duty!” Goneril and Regan mock him in return, “What duty?” Cornwall is furious at Gloucester’s...more

Loyal Gloucester upbraids the sisters for their mistreatment of their father, “Stop him, it’s your duty!” Goneril and Regan mock him in return, “What duty?” Cornwall is furious at Gloucester’s temerity in telling the Queens their duty and orders that he be thrown out, “He will be a companion for the King!” Then the storm invoked by Lear takes over. less

Storm breaks and Lear curses the world

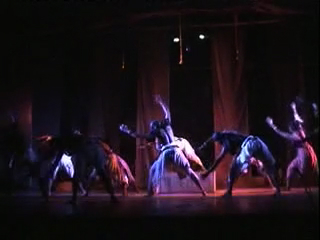

The storm. The Fool searching for Lear and Lear wailing about ungrateful people in despair. Note the choric stylization with music and choreography for the depiction of the storm.

The storm. The Fool searching for Lear and Lear wailing about ungrateful people in despair. Note the choric stylization with music and choreography for the depiction of the storm. less

Cordelia comes to rescue Lear

The voice of Cordelia, calling, searching for the father. Cordelia appears during the storm to rescue Lear: “Did you have to suffer so much?” She finds Lear totally repentant: “Forgive...more

The voice of Cordelia, calling, searching for the father. Cordelia appears during the storm to rescue Lear: “Did you have to suffer so much?” She finds Lear totally repentant: “Forgive me,” he weeps, “Don’t call me father, the word stabs me. I became a victim of words. I banished you. Daughter, forgive me.” Cordelia, mindful of her duty, is generous and loving: “You don’t need to suffer. Come.” She picks him up and takes him away. They exit with Lear leaning on her shoulder.

This was a “happy” ending Lear, in which Lear is seen to have suffered enough humiliation at the hands of the two elder sisters that the idea of his death, so often seen in mainstream criticism, too, as gratuitous, was rejected. Similarly, the death of Cordelia, even more gratuitous, was made redundant. The story was treated as an analysis of power structures in the the famil and the state, in the personal and the public spheres. Hence, though the two elder sisters were shown as equivocating to grab power, they were not made into monsters. Cordelia, on the other hand, was not the angelic, good daughter, but an alert young woman aware of the rights of others. She puts the larger interest of the country – do not divide the kingdom, it’s not fair to the people – before her self-interest, which is inheriting her own portion of the kingdom. Though King Lear had been adapted to end happily many times, the logic of this adaptation partookof the traditional philosophy of all the arts in India, that the primal function of creativity is to show reconciliation, not defeat, of man in relation to God, and it was coloured by the folk form’s pungent variation on it showing how man brings his own suffering upon himself. less

Goneril chastises Lear

Goneril continues her chastisement of Lear: “You are not fit to live in a palace, you think this is a bazaar. You should go live in a temple. You are...more

Goneril continues her chastisement of Lear: “You are not fit to live in a palace, you think this is a bazaar. You should go live in a temple. You are old but you think that your young days will return; your luxuries and demands are too much for me.” Lear walks out in an outraged huff with Kent and the Fool following. less

Goneril’s soliloquy

Goneril’s soliloquy: “I will send advance word to my sister. When he stays neither here or there and is tossed around like a ball, only then will the old man...more

Goneril’s soliloquy: “I will send advance word to my sister. When he stays neither here or there and is tossed around like a ball, only then will the old man learn.” Lear needs to be pulled down a peg or two, but this Goneril, though not so vicious and hard-hearted as usually played, was not devoid of ambition. less

Lear’s third entry, with fanfare and song

Lear’s third entry, en route to Regan’s castle, again riding and miming a chariot to the accompaniment of a choric song from the singers and musicians seated at the rear...more

Lear’s third entry, en route to Regan’s castle, again riding and miming a chariot to the accompaniment of a choric song from the singers and musicians seated at the rear of the stage. The words of the song, “Desire’s an elephant desire’s a horse, and desire’s a welcome and worship with a silver platter,” emphasize that the King is still lusting after ceremonious rituals and his egotism has not abated. less

Fracas outside Regan’s palace

In front of Regan’s castle: Oswald, who has arrived here with a letter from Goneril warning her sister about Lear, sees the King and his party and, acting out his...more

In front of Regan’s castle: Oswald, who has arrived here with a letter from Goneril warning her sister about Lear, sees the King and his party and, acting out his mistress’s ire, trips the Fool. Lear instantly jumps into the fracas, until Gloucester appears, and to prove Lear’s unruliness to him, Kent is produced all bound up, punished for roughing up Oswald and the sentries. less

Kent is released

Lear to Kent: “Did not my daughter protest that it (binding you up) was wrong?” Kent: “She said you will not be welcomed.” To Gloucester, in a rage “My man...more

Lear to Kent: “Did not my daughter protest that it (binding you up) was wrong?” Kent: “She said you will not be welcomed.” To Gloucester, in a rage “My man bound up Why?” Gloucester tries to calm him, beginning his address as “Chakravarty / Lord of the World.” The irony of this is not lost on Lear who immediately rebukes Gloucester by saying, “You call me Chakravarty, but when my man is tortured, you keep quiet!” Gloucester is shamed into releasing Kent. less

Regan tries to reason with Lear

Regan tries to talk to Lear, seemingly more reasonable; she comes and sits next to him and does not adopt the usual imperious or artful manner of most Regans. When...more

Regan tries to talk to Lear, seemingly more reasonable; she comes and sits next to him and does not adopt the usual imperious or artful manner of most Regans. When Lear goes down on his knees, up front, and starts pleading in exaggerated humility, she makes him get up and restrain his histronics. “You should not have left her (Goneril)” she says. less

Lear’s dirge-like grief at rejection

Lear’s dirge like moan of grief when he finally realizes that his daughters are not prepared to give an inch, and that selfishly they are going to keep all that...more

Lear’s dirge like moan of grief when he finally realizes that his daughters are not prepared to give an inch, and that selfishly they are going to keep all that he has given them for their own selves: “When your mother died I was both father and mother to you. I did not put you through the torture of a stepmother. How can you forget all this? I brought you up, made you Queen. Instead of a heart you have iron.” Unfeeling Regan turns around to snap at him, “Don’t repeat the old stories.”

The one and rhythm of a mourning dirge, typical to Tamil culture, along with its set patterns and gestures, give a ring of authenticity to the depth of the rejection and despair that Lear feels at this moment when he has no one to turn to. less

Fool’s satirical Interlude

In an interlude led by the Fool a pungent critique is voiced: the Fool rushes onstage and after a minute of foolery and horseplay with the Sentry, he adopts another...more

In an interlude led by the Fool a pungent critique is voiced: the Fool rushes onstage and after a minute of foolery and horseplay with the Sentry, he adopts another unusual posture, bending over to peer between his legs. This prompts the Sentry to mockingly ask him “What can you see in this upside down position? The King must have gone mad to split the country.” To which comes the prompt reply: “We will understand something – before punishing someone, the Gods make him mad. Not giving to our Chitrangi / Cordelia was wrong. People are perplexed.”

This literal and metaphoric “up-ended view” of Lear’s behaviour again underlines the Fool’s role as a satirical commentator, a role which is both physically and metaphorically concretized on stage. The perspective of the folk form is chimed in consistently. less

Fool introduces the subplot

The Fool introduces the sub-plot, as the story of the rich and the fat ones, with a jibe, the view from below as it were, at Gloucester’s adultery, that “servants...more

The Fool introduces the sub-plot, as the story of the rich and the fat ones, with a jibe, the view from below as it were, at Gloucester’s adultery, that “servants in rich men’s houses should not be beautiful, otherwise they will get big bellied! These are rich men’s foibles and deeds.” Though the Gloucester sub-plot is introduced after the rejection of Lear by Cordelia, it nevertheless has the same universalizing implications in this adaptation. less

Lear’s second entry

Lear’s second entry, with fanfare. He comes, as before, miming the motion and movements of riding a chariot. He goes round the stage to show a distance being traversed, then...more

Lear’s second entry, with fanfare. He comes, as before, miming the motion and movements of riding a chariot. He goes round the stage to show a distance being traversed, then stops center stage and calls out to his Fool: “Vidushaka / jester why are you so quiet? Speak, I am the King who commands.” The Fool’s riposte, “I am allowed to keep quiet, I am a fool, but you are a bigger fool!” keeps up the tradition of critique by the wise Fool. less

Oswald and Kent

Oswald’s impertinence and Kent’s choler.more

Oswald’s impertinence and Kent’s choler. less

Goneril, Oswald and Lear

When Oswald complains about Lear to Goneril, this Lear, more irascible and physical than usual, rushes to strike him with his staff, only to be held back by a curt...more

When Oswald complains about Lear to Goneril, this Lear, more irascible and physical than usual, rushes to strike him with his staff, only to be held back by a curt rebuke form Goneril, “It is my job to punish my servants!” This is the beginning of Lear’s chastisement, and he is already smarting. less

Regan weeps and is rewarded too

Regan does one better, she brings on the tears: “When I think of my father, tears come to my eyes, don’t press me into this public profession of love, tears...more

Regan does one better, she brings on the tears: “When I think of my father, tears come to my eyes, don’t press me into this public profession of love, tears choke me.” Again the interpolated stage business supplements and critiques the action. The Fool, Lear’s alter ego, in a king of ventriloquist gesture, starts scratching Lear’s vanity. This public profession of love is satirized when the rest of the assembled courtiers, and even Lear himself, echo Regan’s crying in a wailing chorus, showing that everyone knows what is to come and can perform it accordingly on cure. Lear gives Regan and Cornwall their portion in accompaniment to a chorus of approval from the onlookers. less

Cordelia’s political protest

Cordelia, in this production has more than the usual words: her arguments against Lear have evolved into political consciousness. Not only does she challenge the vanity of the love-test, but...more

Cordelia, in this production has more than the usual words: her arguments against Lear have evolved into political consciousness. Not only does she challenge the vanity of the love-test, but she also questions the wisdom of parceling off the kingdom: “You are my father, you have brought me up, but dividing the country is not fair to the people, it is against the people.” The Sentry, a commoner, sends up a quick cheer in support of Cordelia, underlining the grassroot perspective that is integral to the folk theatre forms. less

Goneril and Regan rebuke Cordelia

Goneril and Regan immediately, and sycophantically, jump to the defense of Lear. They sharply rebuke Cordelia: “How dare you insult our father!”more

Goneril and Regan immediately, and sycophantically, jump to the defense of Lear. They sharply rebuke Cordelia: “How dare you insult our father!” less

Kent intervenes and is banished

Kent intervenes in support of Cordelia: “She is speaking the truth, you should respect her, she deserves justice,” and is thrown down and banished for his pains. The expressionistic physicality...more

Kent intervenes in support of Cordelia: “She is speaking the truth, you should respect her, she deserves justice,” and is thrown down and banished for his pains. The expressionistic physicality of the staging is seen in Lear’s angry tapping of his staff, his throwing down of Kent, his jeering laughter and the raising of his stick to hit Kent until stopped by Gloucester. It emphasizes the egotistical quirkiness of Lear’s behaviour. less

Cordelia’s final statement and her banishment

Cordelia continues: “Why do my sisters have husbands, if they say they love you all? … Don’t divide the country, it’s not in the interests of the people.” Her repeated...more

Cordelia continues: “Why do my sisters have husbands, if they say they love you all? … Don’t divide the country, it’s not in the interests of the people.” Her repeated independence of view infuriates Lear: “Am I mad?” He then jumps around, bangs down his crown (the Fool who both mimics and mocks him does the same) and flounces off without giving Cordelia anything, “I disinherit you.” She calls after him, “Appa / Father,” but to no avail. The Fool, calling “Tatta / Grandfather” rushes after him. less

The elder sisters corner Cordelia

The two elder sisters accuse Cordelia of angering the father and ruining his public ceremony. Then Albany intervenes to express his reservations: “I don’t like what is happening,” only to...more

The two elder sisters accuse Cordelia of angering the father and ruining his public ceremony. Then Albany intervenes to express his reservations: “I don’t like what is happening,” only to receive a cutting rejoinder “What did you get by tellingthe truth?” from Goneril. She mocks him, “You are a coward. I will take care of the kingdom.” “That is what I am worried about,” retorts Albany. They all stride out leaving Cordelia alone and subdued on stage. This was an inverse “leave taking,” with Goneril and Regan taking the upper hand. Cordelia’s marriage to France and later return as Queen to England was deleted from the plot. Cordelia became a more single minded and independent character. less

Fool’s perspective

The Fool’s rolls and somersaults bring him face to face with a Sentry who mockingly asks him “What are you doing, rolling about? Are you performing the angapradakshanam prayer (ritual...more

The Fool’s rolls and somersaults bring him face to face with a Sentry who mockingly asks him “What are you doing, rolling about? Are you performing the angapradakshanam prayer (ritual of body rolling in a circle)? To which the Fool replies, “No, that is the King’s pushishment.” “How is rolling a form of punishment? And why are you singing while rolling?” questions the Sentry, again. The Fool explains, “That is the meaning, the King is the deceived one … Don’t hit me (when the Sentry cudgels him)… Do you know that the King is going to suffer – he is going to make three pieces … today the King will distribute something, he has decided…”

The reference to the king reminds the Fool of his duties, which include heralding the king who is about to arrive. The two, Fool and Sentry join together to call out the elaborate epithets of the king, but their tone and comic knockabout manner is satirical. The implication of the dialogue and the stage business is that the Fool’s posture and perspective, not upright but rolling about, though seemingly absurd, derives from a prayer ritual and gives him a truer insight into a world which is irrational to begin with. It becomes a forewarning of the suffering as punishment that Lear is about to undergo. This is the characteristic idiom of the folk form, terukutoo, where a robust playful physicality critiques the more straight-laced world. less

Lear’s entry with fanfare

Lear’s entry is in the traditional mimetic fashion; he comes, heralded by drums and flutes, swaying to the jogtrot movements of his chariot. Suddenly, he stops everything, jumps up, and...more

Lear’s entry is in the traditional mimetic fashion; he comes, heralded by drums and flutes, swaying to the jogtrot movements of his chariot. Suddenly, he stops everything, jumps up, and then restarts the music, to be quickly followed by a sign for the music to stop again. This Lear is immediately signaled as a whimsical tyrant asserting a total control over his retinue who literally sing, dance, laugh, site, stand and jump to his tunes, and one who has a childish (juvenile) delight in making them do so.

Notice the “open” stage with partial flats at the back showing the seated musicians, and allowing quick entries and exits in full view of the audience. This king of open stage with the entire cast seated on stage, and with live music and miming is again characteristic of the non-illusionist style of the folk from terukutoo. less

Lear narrates his intent

Lear narrates his intent: “I wish to retire and will divide the kingdom / country intro three parts. But first let me see how much they love me. They have...more

Lear narrates his intent: “I wish to retire and will divide the kingdom / country intro three parts. But first let me see how much they love me. They have affection, that is well known, but in vying with each other, their professions of love will be like honey to my ears. For the satisfaction of my ears let me listen to them.” The Sentry’s question, “What purpose will it server?” is a critical comment on this whimsical plan.

Note how Lear takes off his angavastam (body cloth) and not his headgear when he announces his intent to retire. The angavastam, a symbol of honour is used in several scenes for a telling dramatic effect. Note also how the Fool is constantly mirroring, in a comic exaggerated manner, the king’s actions and gestures. less

Goneril and Regan are heralded

The two elder daughters enter announced by the Fool and to the accompaniment of a musical fanfare. Lear rushes to them with obvious pleasure. Note the tribal dress (not group...more

The two elder daughters enter announced by the Fool and to the accompaniment of a musical fanfare. Lear rushes to them with obvious pleasure.

Note the tribal dress (not group specific) of all the characters which along with their shrill voices, lack of courtliness of manner and polish in language was part of the attempt to de-canonize Shakespeare, turn the play intro street entertainment for the ordinary people which is what the terukutoo is meant to do. less

Cordelia enters separately

Cordelia enters later, separately from her sisters and bows to Lear. This adaptation has a feminist slant, therefore it did away with the formal ritual of feet touching, seen in...more

Cordelia enters later, separately from her sisters and bows to Lear. This adaptation has a feminist slant, therefore it did away with the formal ritual of feet touching, seen in Samrat Lear. less

Lear’s announcement of the love-test

Lear announces the love-test and the division of the country: “I want to hear with my own ears how much you love me.” Cordelia intervenes in protest.more

Lear announces the love-test and the division of the country: “I want to hear with my own ears how much you love me.” Cordelia intervenes in protest. less

Goneril speaks and is rewarded

Goneril / Kanaka’s professtion of love and Lear is hugely, and literally, “tickled” by her words. Happily flattered, he gives her her due. Broad gestural play and expressionistic body language...more

Goneril / Kanaka’s professtion of love and Lear is hugely, and literally, “tickled” by her words. Happily flattered, he gives her her due. Broad gestural play and expressionistic body language is integral to terukutoo and is used to simultaneously support and critique the characterisation throughout the production. Lear’s scratching of his back himself is a piece of theatrical physicalisation that functions as a satiric comment on his love-test, which, in actuality, is a huge ego-massage for him. less

Lear’s madness

Lear’s humilation turns to rage: he begins to curse the world and invokes a tempest, cosmic destruction and the end of the world. “Blow wind, etc. ” … He then...more

Lear’s humilation turns to rage: he begins to curse the world and invokes a tempest, cosmic destruction and the end of the world. “Blow wind, etc. ” … He then begs for patience, and has a foreboding: “King, looks like you will be mad, run, run, from here,” says he running off the stage. less

Cordelia’s “nothing”

Lear turns invitingly to Cordelia only to be hit by her “Nothing!” He almost loses his non-chalance and his balance on his stick, fumbles, and retort’s “Nothing will come of...more

Lear turns invitingly to Cordelia only to be hit by her “Nothing!” He almost loses his non-chalance and his balance on his stick, fumbles, and retort’s “Nothing will come of nothing, speak again.” less

Prologue: the making of a Fool

Prologue: Unlike the other two productions, this version of King Lear is an indigenisation of the play according to the dynamics of the terukutoo is an improvisatory dramatic form, which...more

Prologue: Unlike the other two productions, this version of King Lear is an indigenisation of the play according to the dynamics of the terukutoo is an improvisatory dramatic form, which is liberally interspersed with music and dance. Its distinguishing characteristic is a rough and ready critique built into the playing through the improvisatory liberties given to the komali or the vidushaka / fool figure. The creative innovation of the performance is to use this convention of the folk form to comment on the heart of the play, i.e. the folly of the king.

The play thus opens with a roll of drums and the lights slowly coming on. Upon which a figure leaps in, is chased around, picked up, sat upon (literally), surrounded, and when the captors move away, he is discovered painted into a fool! The sequence ends with the character shyly accepting that “Now I am case as the joker / fool / komali.” less

Fool’s song

He proceeds to act out the Fool, indulging in all the acrobatics of a fool: rolls, somersaults and leaps, and then starts to sing in a mocking tone: If you...more

He proceeds to act out the Fool, indulging in all the acrobatics of a fool: rolls, somersaults and leaps, and then starts to sing in a mocking tone:

If you use a headgear you are the master

If you wear a cap you are a fool

I have been given the dress / role of the fool…

The song celebrates the paradoxical equation between the king and the fool, which became the central trope of this production. Since the Fool remains present till the end in this adaptation, his function as an alter ego of the king becomes more emphasized. less

Essays

Shakespeare in India: Modes of Performance

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional.more

- Universalized Shakespeare

- Localized Shakespeare

- Indigenised Shakespeare

- English Language Shakespeare

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional. These are artists who do not earn their main living in theatre, yet devote all their leisure and creative energy to it, run theatre groups and even travel with their shows to different parts of the country. Bhuthadia’s group, Pratyaya, chose to perform Lear inspired by the much acclaimed translation by Vinda Karnadikar, eminent Marathi poet, who is able to capture the nuances of Shakespeare’s language without sacrificing its images or allusions.

A faithful translation, it was performed in a manner ‘faithful’ to the tradition of realist staging of Shakespeare. This has been the most common staging practice for Shakespeare in India. Based on universalist assumptions of a stable and authoritative text, it performs Shakespeare straight letting the text speak for itself. It seeks to let the past live in the present, playing up its foreignness. Though sometimes critiqued as “derivative” and “essentialising,” this universalist staging practice, particularly in our colonial and postcolonial context, functions as an empowering mimicry. “Doing it like them” becomes a mastering of the master colonising text.

Further, the group, Pratyaya, coming from a provincial town like Kolhapur, is able to eschew the market rules of Bombay theatre: “Ours is a focused outlook on theatre,” says Sharad Bhuthadia, asserting that they choose to do meaningful theatre which can “go beyond and handle genuine human problems by going deep into the understanding of man’s life” (quoted in a review, Independent Journal of Politics and Business, 20 August 1993). Bhuthadia’s Raja Lear thus did not need any further entry points into the play, and while it performed an edited version, in three acts, it nevertheless, did full justice to the main themes of the play.

Its singular achievement was a deeply felt and internalized performance, not always easy for Shakespeare in translation; it received universal praise: “A high-powered fidelity to a Shakespearean text…. Never before had Marathi sounded so good on stage. Raja Lear was not just believable, it was real,” said R Ramanathan in the Independent Journal, while the Indian Express (20 August 1993) titled it a “Class Act.”

So successful was the universalizing of this production that critics had no difficulty in contemporising the play: “Lear becomes the tragedy of the India we are living in – the tragedy of a great nation being torn apart by centrifugal forces: of a political class composed of an imbecile king surrounded by sycophants (Regan and Goneril) and ruthless manipulators (Edmund); of the voices of sanity being disowned (Cordelia) and banished (Kent) or simply disappearing (Fool); of goodness having to pretend insanity (Edgar). Lear, then, does not remain the tragedy of one man. It becomes the tragedy of an entire people, an epoch.” (Sudhanva Deshpande, The Times of India, January 1993).

The localized Shakespeare is another performative style, particularly favoured in the earlier years, which imported a definite Indian flavour and colouring to transform the alien vastness of the text into an accessible familiarity. The degree of change varied: while the adaptations of the Parsi theatre in the 1880s took great liberties with Shakespeare’s plot, character and even words, the post- independence localizations have been attempts to root Shakespeare more acutely in a specific local ambience. The production, chosen to illustrate this stream of performance, is a student production of the National School of Drama. Samrat Lear, directed by John Russell Brown.

The National School of Drama, in New Delhi, has a tradition of inviting directors from different parts of the country and from abroad to train their students in a variety of performative styles. Visiting English directors have often chosen to direct Shakespeare even though the performances are always in a Hindi translation. John Russell Brown’s production played almost the full text – a marathon three and half hour long performance – in a translation by Harivansh Rai Bachchan, one of the foremost Hindi poets of the twentieth century. Brown’s own closeness and expertise with the English text gave the production sharply etched characterisation, robust energy, and a particular focus on the narrativisation of the story.

Its localization was not to resituate the story in another well-defined place or period, but to let its relocation emerge from the theatrical event in Delhi. “I have not localised the story in any specific way,” Brown said in an interview with the author, “because we were not doing an “authentic” Indian production. I wanted this Lear to speak beyond the moment.” To this end, he said, he had “encouraged the [student] actors to use their own ‘folk’ physicalities, (their own understandings of their theatre traditions) in their responses to s,” because he believed that a “play lives between the actor and the audience.” The result was a fairly successful attempt to meld the conventions of the traditional theatre, the style of the modern Indian theatre with the speech rhythms of Hindi onto the story of Shakespeare.

Traditional Indian costuming and music added the finishing touches. As Kavita Nagpal, seasoned theatre critic, remarked, the production made “the play breathe in a way that was both historical and contemporary” (Hindustan Times, 15 March 1997). Both these productions, the universalized Shakespeare, Raja Lear, and the localized Shakespeare, Samrat Lear, though divergent in their performative styles, shared a conventional interpretative stance. They ventured no innovative critical perspectives on the text, trusting a ‘straight’ telling of the tale. They both proved that Shakespeare in translation could successfully speak to its audiences.

The indigenised Shakespeare is perhaps the most creative and, therefore, somewhat controversial form of staging Shakespeare in India. Here, the Shakespeare text is not just adapted but appropriated and acculturated into an indigenous theatre form. Devotees of the literary text find this kind of transformation a desecration; yet successful indigenisations, which immerse Shakespeare’s text into another aesthetic and cultural worldview, can spark off new meanings and fresh configurations of the same text. The production chosen to illustrate this genre of performance is a rewritten version of Lear entitled Iruthiattam (The Final Game) directed by R. Raju from a Tamil translation and adaptation made by well-known novelist and playwright, Indira Parthasarathy and presented by the theatre group, Arangam. R. Raju, from the School of Performing Arts at Pondicherry University, and a former NSD graduate, belongs to the Kerala school of experimental theatre, the ‘nataka karali,’ making appropriation and adaptation his metier. And Arangam is no ordinary theatre group either; it consists of highly skilled artists – dancers, musicians and folk theater practitioners – in their own right. Together they created a tightly structured, economical production distinguished by consistency and unity of rasa or mood. It interprets the play in terms of a power struggle, retains part of the sub-plot to make a feminist point that sons too can be cruel, and ends with the storm scene at the end of which Cordelia appears to rescue Lear.

But its indigenisation derives more from its performative style, which adapts the conventions of the terukutoo, a popular street theatre folk form of Tamil Nadu, traditionally performed by the socially disadvantaged. The inherent subversivness and spontaneity of the terukutoo, centering on the improvisatory energy of the fool I komali, was the main interpolation into the text and this was specially manifested in the highlighting of a contrapuntal relationship between the fool and the king. The strong phyicalised style, acrobatic and earthy, with its vigorous song and dance routines, made Iruthiattam lively and entertaining, transforming King Lear from a reworked classic into a kind of a ‘people’s Shakespeare.’

Even though the adaptation was titled “The Final Game” it did not in the least subscribe to a Beckett-like doom and gloom of Endgame. Since this version took liberties to play around with and cut up Shakespeare’s canonical text to suit its own radicalising perspective, it may also be seen as an example of the postcolonial Shakespeare.

Apart from these, the English language Shakespeare is best represented by an amateur student production of King Lear by the St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, one of the oldest collegiate dramatic societies with an almost unbroken record of performing Shakespeare for over 75 years since 1924. Arjun Raina, a young actor director worked closely with the students drawing out their impressions and structuring them into stageble ideas. The production was marked by an iconoclastic irreverence, at times a plainly undergraduate-ish swipe at tradition, which nevertheless produced some novel stage images, e.g. the introduction of a whimsical Lear in boxer shorts and gloves brought onstage reclining in a brightly coloured coffin symbolizing the death of the monarch.

The rest of the cast sat on and moved around with high but crude wooden stools that wobbled and wavered at every step, imaging Lear’s world as full of social climbers caught in the instabilities of the social hierarchy. The characteristic opening sequence had all the court, clad in black and white, looking harlequinesque, streaming in to ‘view’ the show of Lear’s division of the spoils through tinseled masks and opera glasses (these were changed to dark glasses after the blinding of Gloucester) as also looking, observing, spying on each other – all heightened, perched on the wooden stools. Lear chased his screaming daughters down the stage and then pieces of cake were passed around during the division of the kingdom.

Though this production was peppered with more deconstructive sallies than it could ultimately pull through coherently, it was unusual in the liberties it took – informed by the iconoclasm of contemporary western staging practice – because the norm for the English language collegiate Shakespeare, performed for a pedagogic purpose, has been a traditional staging in period costume. less

Shakespeare in India: Chronology of King Lear Productions in India

1832 Scenes, Lear (III.iii), English, Chowringhee Theatre, Calcutta. 1880 Atipidacarita, Marathi, tr./adapt. S M Ranade, Aryodharak Company, Poona. 1897 Rajavu Lear, Malayalam, tr./dir./actor Govinda Pillai, Trivandrum. more

(Citing language, translator, director, group and place based on available information).

1832 Scenes, Lear (III.iii), English, Chowringhee Theatre, Calcutta.

1880 Atipidacarita, Marathi, tr./adapt. S M Ranade, Aryodharak Company, Poona.

1897 Rajavu Lear, Malayalam, tr./dir./actor Govinda Pillai, Trivandrum.

1906 Har Jeet, Urdu. Munshi Murad Ali, dir. David Joseph. Victoria Theatrical Company, Bombay.

1907 Safed Khoon, Urdu, Agha Hashr Kashmiri, Parsi Company, Bombay.

(1919) ” ” Jalal Ahmed Shah

1962 Lear, English, St Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society with Roshan Seth, Delhi.

1964 Raja Lear, Urdu, tr. Majnoon Gorakhpuri, dir. Ebrahim Alkazi, National School of Drama, Delhi.

1977 Raja Pagala Aur Teen Betiyaan, Hindi, Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Kala Parishad, dir. B.V. Karanth (Bhopal Rang Manch 1978?).

1978 Lear, Marathi. readings, V. Karandikar, (tr.) Indian National Theatre, Bombay

1978 Mannan Lear, Tamil, tr. Aru Somasundaram.

1981 King Lear, Urdu, tr. Majnoon Gorakhpuri, dir. Barry John, NSD, Delhi.

1982 Teen Kanya, Bengali, tr./adapt. Amar Ghosh, in jatra form with Shamul Ghose.

1984-5 Nandabhupati, Kannada, tr. Gopal Vajpayee, dir. Jayatirtha Joshi, at Gadag, Dharwar.

1985 Hemchanda, Kannada, tr. Puttanna, dir. B.Suresh, Bangalore Chitra Abhinayaranga, Bangalore.

1986 Raja Lear, Bengali, tr./dir./actor Salil Bandhyopadhyay, Theatron, Calcutta.

1986 Raja Lear, Hindi, tr. Atul Tiwari dir. Fritz Bennewitz. NSD ?, Delhi.

1988 Raja Lear, Hindi, dir. Fritz Bennewitz, Padatik, Calcutta.

1988 Lear, Kannada, tr. H.S. Shiva Prakash, dir. Raghunandan, Tirugata (Repertory) Ninasam.

1980s Lear, Bengali, tr./dir. Amar Ghose. Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta,

(late)

1989 King Lear, Urdu/Hindi, tr./adapt. Neelabh, dir.Amal Allana, Television and Theatre Associates, Delhi.

1990s Lear, Kannada, tr./adapt. B Chandrashekar, for 2 chars, female’s story in flashback, by A. S. Murthy.

(early)

1991 Shakespeare Namaskara, Kannada. Scenes, dir. Fritz Bennewitz, Rangayana, Mysore.

1991 Lear, in Kathakali, dir. Leday and McRuvie, Bombay.

1992 Lear, Kannada, Sagar, one man show.

1993 Raja Lear, Marathi. tr. Vinda Karandikar, dir. Sharad Bhuthadia, Pratyaya, Kolhapur, performed over the decade in Bombay, all over Maharashtra, in Calcutta and in Kasargode.

1996 King Lear, English. Indian Summer Theatre Company, U.K.

1996 King Lear, English, dir. Arjun Raina, St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, Delhi, also in Calcutta.

1997 Samrat Lear, Hindi, tr. Bachchan, dir. J R. Brown, NSD, Delhi.

1997 Lear, Kannada, tr. H.S. Shiva Prakash, dir. B.V. Karanth, Prakash Karnataka Natya Akademy Drama Workshop for teachers, Mysore.

2001 Iruthiattam, Tamil tr./adapt. I. Parthasarthy, dir. R. Raju, Kasargode, also at Bharangam 2002, Delhi.

2002 Pagala Raja, Hindi, tr./adapt. Neelab, dir. C. Basavalingaiah, NSD, Delhi. less

Shakespeare in India: History of King Lear in India

King Lear is an appropriate play with which to illustrate these tendencies and periodisation in the performance history of Shakespeare in India.more

King Lear is an appropriate play with which to illustrate these tendencies and periodisation in the performance history of Shakespeare in India. One of the more frequently performed tragedies, it spans all these streams and periods and, in the last twenty years, particularly, it has become a kind of a measure or testing ground of actors and theatre groups. Its first performance in India was in 1832, when some scenes, in English, were done at the Chowringhee Theatre. Calcutta. During the period of ‘adapted’ Shakespeare, from the 1860s to the 1910s, in the 1880s a happy-ending version of Lear, Atipidacharita (The story of the intensely wronged one), influenced by Nahum Tate, in Marathi, became popular in Bombay. Another adapted and localized version, Safed Khoon (White Blood or Filial Treachery) by Agha Hashr Kashmiri, for the Parsi theatre in 1906, achieved commercial success and was played throughout the country.

1897 saw one of the first faithful translations, A. Govinda Pillai’s Malayalam version, Brittanile Rajavu Lear, being staged in Trivandrum, with a meticulous realism which included imported costumes and accessories, before a select audience and with a select cast – noted novelist and playwright C V Raman Pillai played Lear. However, as a performed text, the moment for King Lear in India arrives after independence. St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, Delhi, staged Lear in English, in 1962, with a young Roshan Seth – who went on to achieve greater recognition on the international stage and screen – as Lear. Ebrahim Alkazi, one of the foremost contemporary directors, produced a Raja Lear, in Urdu translation, for the National School of Drama in 1964, a production that has become a benchmark of the universalized Shakespeare. In the 1970s several productions in Hindi, Marathi and Tamil are to found, but it is in the eighties that the play comes fully into its own in India. As many as twenty one productions can be listed from this period, in several languages, including Bengali, Kannada, Hindi, Urdu, Marathi, Malayalam and Tamil, in all the different performative modes, of the localized, universalized, indigenised, English language and postcolonial Shakespeares.

Indian audiences have found many affinities with the story of King Lear. An Indian folk tale of an aging maharajah who is brought to grief when he puts the love-test to his three daughters before dividing his kingdom resonates with the same issues. He is shocked to hear the youngest daughter, his favourite, announce that she loves him like salt, a necessity – no more or less – and in anger disinherits her to suffer at the hands of the other two. The idea of banishment and exile as a form of penance, and suffering as atonement for wrongs committed are well-known concepts central to the great Indian epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata.

In everyday life, familial and generational conflict is familiar given the deeply patriarchal setup of Indian society. Further, the power struggle within a family and, by consequence, within the nation is reminiscent, for many readers/viewers, of the contemporary political scene in India where one family continues to be closely identified with the fortunes of the nation. It is the presence of such wide-ranging affinities from within their own culture, ancient and contemporary, that have made Indians take to Shakespeare in general, and King Lear in particular, in a big way. Shakespeare’s own setting of the play in a pre-Christian, quasi-pagan context, facilitates such equations. less