Shakespeare has held an active place in Brazilian academics and stages for decades, including the production of world-renowned performances that have made their way to the Bard’s England, as well as to other prestigious arenas. The COVID-19 pandemic drastically affected much of what happens in the theater, but surely it has not affected the status and presence of Shakespeare in Brazil. An impressive variety of creations have taken place in the recent times of isolation and social distancing, and have brought with them some contributions to theater both during the pandemic itself and also after the vaccines and reopening of the auditoriums. In this text, I present some of the most significant digital performances and creations originated in the country at the time of such crisis.

Let us begin with Titus Andronicus, a play that has been gaining more and more attention and, let’s face it, is not easily digested in reading or attendance due to its severe violence. Titus Andronicus – o rosto da guerra – uma experiência analógica para tempos virtuais (Titus Andronicus – the face of the war – an analogic experience to digital times) was developed by the collective bobik & sofotchka, a group of seven women under Marcia Nemer’s direction. The idea, prior to the pandemic, was to offer a regular, live performance on stage. With the closure of the theaters, the collective changed it not to online theater, but to a sort of theatrical experiment. In this experiment, the first part was digital: weekly videos were released on the collective’s Instagram account (three short videos per week, adding up to ten videos in total, the last one anticipating an explanation of what would come next), and in these materials the actresses reported on the process of studying and developing the play for performance. This opening of the experiment ended with a live broadcast (or better saying, seven simultaneous live transmissions), in which the seven actresses, each one isolated in her own Instagram account, would read the same excerpt of Titus Andronicus’s adaptation for the stage. The audience could navigate through the transmissions, as they would be performing the same text.

And then came the second, analogic part of the creation: the collective sent through regular mail service a total of 100 letters, one to each attendee, with instructions and guidelines for the participant’s active engagement with the experiment. In the activities explained in the letter, the participant had the chance to do things with Shakespeare’s text, following also some clues left by the collective on their social media. If we look at the whole idea, we can clearly observe the urgency of discussing and better understanding theater as an art, in digital times, and in times of crisis, faced with the challenge of continuing the show at the same time as adapting it, in a process through which such adaptation puts in question one of the core elements of the theatrical event: the live presence and communion among its participants. The collective was audacious in mixing the digital with the analogic, in putting the spectator in such an active (and much welcome) position, and in raising the point of how hard it is to be part of a collective (their own name, and their very status as a troupe) when clearly everyone is isolated. How can we be and do theater “separately together”, is what they seemed to ask.

Titus Andronicus, o rosto da guerra

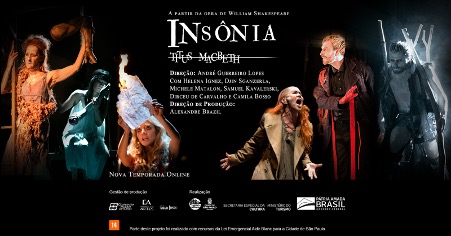

In spite of not being one of the most performed plays, Titus received another important space, before and during the pandemic. Back in 2019, there was a show with sold out sessions and award nominations, called Insônia – Titus Macbeth (or, Insomnia – Titus Macbeth), by André Guerreiro Lopes. It gathers two terrifying tragedies together, and in the in-person performance, the audience would move around the actors so as to choose various points of view and what to observe in the development of the scenes. With the pandemic, the show was transformed to an online version, in which the performance was filmed in different days and with three cameramen moving around in the way spectators would have done before, choosing angles, frames and cuts. Then the material was mixed with rehearsal scenes, including the use of binaural sonority – so the sounds from actors’ voices, for example, may seem to come from different points from the screen, each time. The online experience, an adaptation to explore the potential of audiovisual languages and film techniques, still made sure the spectator would have an important and active role at the center of the reception process.

Insônia – Titus Macbeth

The next two cases to be reported probably got more visibility for regular theatergoers in Brazil, not due to their originality, per se, but because they involved famous actors, of that type that gets recognized on the streets and gathers fans to take photos wherever they go in Brazil. Quem está aí? – Monólogos de Shakespeare (or, Who goes there? – Monologues by Shakespeare) was directed by nobody less than Ron Daniels, a much celebrated Shakespearean specialist and theater director. The title echoes the famous opening of Hamlet. The actor Thiago Lacerda performed to a camera a selection of monologues from Hamlet, Macbeth, and Measure for Measure, all of which were broadcast via SESC São Paulo’s Youtube and Instagram accounts. Daniels and Lacerda had worked together on acclaimed performances of the three plays since 2012, being highly praised by the audience and critics. The online adaptation of the performance took place just a few months after the beginning of the pandemic, and the actor’s perspective of the experience is part of what makes it interesting to be shared. Because it was not a Zoom (or similar) event, with live interaction and somewhat more intimacy, but rather a performance to a camera, it felt quite strange for the actor. He claimed he had felt alone, in spite of being watched simultaneously by over a thousand attendees. In fact, Lacerda stated that “maybe” what they did should be called by another name, rather than theater. Still, he says the event was at the same time “uncanny, challenging, revealing, gratifying, powerful and communicative”[1], and even describes a feeling of “hangover” the next day, as if he had had the opening night of a traditional, in-person performance. It gave him an opportunity to connect with the text in a different manner, and he says it is unfair to judge whether it was better or worse.

Quem está aí? – Monólogos de Shakespeare

Another “one-man show” that gained a lot of attention, and again, particularly for involving a well-known actor in the country, is Os vilões de Shakespeare (The villains of Shakespeare), based on the text by Steven Berkoff. The performance offers a combination of acting with lecturing, with selected excerpts explained and discussed. Performing it was a famous soap opera and film star, Marcelo Serrado, and the direction was by Sergio Módena, an important director with respectable and innovative works under his signature. Also, like in Thiago Lacerda’s case, it came from a much acclaimed previous performance in the traditional in-person scene, back in 2017. It was then transformed to meet the digital scenario, having as one of its goals to share the revenue so as to aid artists in general, who were much affected by the impossibility of working during the times of isolation. In this performance, Serrado left his house already dressed as his character, and he would actually go to the auditorium and perform on stage to a nearly empty[2] theater: there was only one spectator in person, three cameras, one technician, and a thousand virtual spectators on Youtube. The reason to sell one in-person ticket was that this single attendee would symbolize the crowded auditorium.

A relevant aspect to be added is Marcelo Serrado’s views on online theater in the (quasi) post-pandemic times. During the event, he mentioned the importance of art resisting the crisis. And now, at the dawn of a nearly “normal” life again, in spite of the difficulties of a new way and platform of performing, he believes some of the learnings and innovations from online theater came to stay. Among these, he mentions the use of cameras to reach people who, otherwise, would not be able to go to the theater, as well as the possibility of providing different angles to the staging.

Os vilões de Shakespeare

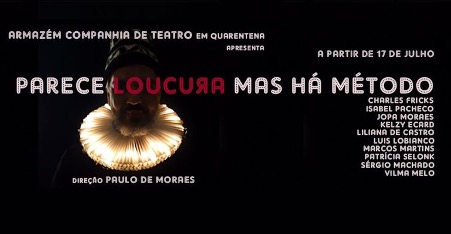

The next work I wish to highlight is called Parece loucura, mas há método (a translation of Shakespeare’s line “Though this be madness, yet there is method in ‘t”, found in Hamlet), by Companhia de Teatro Armazém. This case was not only original but also clever in its functioning, and gathered important theater actors to play with the spectators through Zoom, at the same time that the emphasis was clearly on Shakespeare’s words. It was a performance and a game at the same time, in which the actors would not reveal which role they were playing, and the spectators would choose who to eliminate through online polls, after “battles” that had been defined randomly. Not only was this active role for the attendees of remarkable creativity, but they also faced an extra fun challenge of trying to identify the characters and plays that they had come from. Directed by Paulo de Moraes, the performance included a Master of Ceremony, played by Sérgio Machado, in charge of explaining the rules and being the host of the meeting – just like in real (online) life. A peculiar aspect to be added is the non-repeatability of the event, in the fashion of “traditional” ways of doing theater, but in a more prominent manner: while the plot of an in-person performance usually repeats night after night, in the case of “Parece loucura, mas há método”, in each performance the random definition of the characters involved in a given battle would change, as well as the result of the elimination phase.

Parece loucura, mas há método

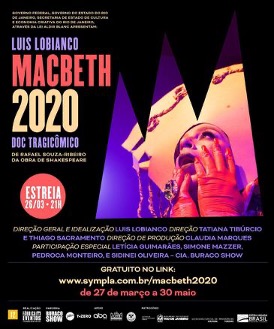

Now we shift to a production that emphasized humor, in spite of centering around a tragedy. Macbeth 2020, a production by Luis Lobianco and participants of the Cia Buraco Show in partnership with Teatro Poeira and TV Zero, was actually referred to by its creators as a “performance-film-documentary” or a “film-theater”. It consists of seven recognizable archetypes played by Lobianco, all from the theater industry in the 1980s and 1990s in Brazil. The characters report their difficulties in trying to produce “the Scottish play” in what is presented as a sensationalist and fake documentary. These reports are intertwined with archive images of the characters struggling to perform the play, following the text’s original chronology. It created a play within the play frame, in a fusion of theater art and audiovisual languages. Lobianco’s perspective is that the pandemic brought with it enough tragedy, and the comic path was the way to pay homage to the artists and workers of the cultural field, in much need of support and faith at the time.

Macbeth 2020

A much awarded Brazilian company that specializes in producing Shakespeare in a humorous way, and particularly for younger audiences, also innovated in offering the audience its works even with the closure of the theaters. Companhia Vagalum Tum Tum, directed by Angelo Brandini, had an adaptation of Richard III ready when the pandemic hit the country, and the opening night had to be (long) postponed. Among the many things they did in the period of isolation was to prepare a podcast of the play to play on Spotify. Meu reino por um cavalo (which refers to Richard III’s quote, “My kingdom for a horse”) was organized in eight episodes, lasting an average of 10 minutes each, and included the soundtrack they always perform live when on stage, to follow the events they perform orally, but not visually.

It is interesting to add that the company was smart enough to join the tendency of podcasts which, in Brazil at least, became much more popularized[3] because of the pandemic. And as of the writing of this text (in August, 2022), they got the chance of opening the show on stage, and continue their amazing work with introducing Shakespeare to children and teenagers.

Meu reino por um cavalo

Of course Vagalum Tum Tum makes Shakespeare’s terrifying tragedies digestible to their young audiences, and one of the strategies they used was, as expected, with the use of humor and comedy. These seemed even more needed at the most difficult periods of the pandemic, with the recommendations to social distance and stay at home. Another initiative that had bet on humor, but in this case aiming at the adult audience, was the online project called Quem vem lá? (in Portuguese, a variation of Hamlet’s opening, Who goes there?), an independent production with two professional actors. It was broadcast on Youtube, Spotify and Google Podcasts in the period of three weeks, with one episode that would parody a talk show being released each week. What does it have to do with Shakespeare? Simply the fact that the interviewees, in the parody, are some of the most famous characters of the Bard. The first episode involved characters of Hamlet, the second, from Romeo and Juliet and, to end it, Macbeth. All characters were played by actors Janaína Batista and Mateus Gomes, who opened the sessions with brief information about the plot and its cultural legacy. When performing the characters, they would not be short on slang use, swear words, regional terms and irreverence. Even the ghost appeared briefly, and was of course much applauded by the fake audience of the podcast. Even though it was not a hit in terms of having a large audience, the production is noteworthy for its creativity and audacity.

Another production that was not a performance of a play per se, but a freer creation based on Shakespeare’s texts, is O príncipe (The prince), by Indelicada Cia. Teatral. The group had actually been on stage with it back in 2015, both in Brazil and abroad, and was ready to tour the country again when the pandemic hit the world. They were, as many others, forced to adapt themselves and their work. What they did was anticipate doing online theater, something they stated that was already a wish and a plan before COVID-19. In this show, two clowns tell the story of Hamlet, and because there are clowns at the center, the tragic plot is reshaped with humor as well as melodramatic elements. The use of memes and politically inappropriate language, not to mention references to the real-life political scenario of Brazil, permeate the performance. With influence from Maquiavel’s text, the focus is on the rotten condition surrounding Denmark. The direction is by João Bosco Amaral, and the cast includes Evandro Costa and Ricardo Fiuza, and it can be watched on Youtube. The main changes to going online were mostly of a technical nature, and as stated by the director, it was needed to pay more attention to details that may gain more prominence on the small screen, if compared to the large auditorium, such as make up, costume and lighting design. However, it must be said that this is clearly not a case of “filmed theater”. In fact, what the direction looked for was a fusion of theatrical and audiovisual languages, generating something of a hybrid nature. The clowns first meet in the seating area of the auditorium, then move to the stage and perform the show. In the epilogue, they play the role of the very spectators watching from home, in a creative metalinguistic commentary on digital theater. A peculiar aspect to be added to this description is their positive take on the visibility and potential of reaching more audiences, for being online. Another final thing to be said is that, together with the online performance, they also were careful to develop formative activities adapted to the online format: theatrical games for kids and teenagers, and communicational accessibility in performances, for producers, actors and directors, as well as sign language interpreters.

O príncipe

The next presentation also involves a concern with offering workshops and debates during digital times, in active exchanges between artists and the public. The group Pandemônio em cena prepared an exposition of solos based on The winter’s tale, titled Pandemônio em criação: Solos Shakespearianos (Pandemonium in developing: Shakespearean solos). The project was initiated during the COVID-19 isolation period, and in light of the unknown and feared scenario presented, they deliberately chose The winter’s tale to conduct a research on pandemic times. Inspired by events that are crucial to the play, such as the passage of time and the premature loss of beloved ones, the work of the group was aided by historian and researcher Ricardo Cardoso. They offered to the audience on Instagram, Facebook and Youtube a workshop on creating and using theatrical masks, and nine solos originated with the research. As described by one of the actresses, Gabrielle Paula, it became an opportunity for the artists to understand and live their anxieties through art itself, particularly in times of much uncertainty and difficulties for the theatrical workforce.

Pandemônio em criação: solos shakespearianos

ShakeCena Cia de Pesquisa Teatral, with artistic direction by Eliete Cigaarini, has been an active group in the Shakespearean scene. Since the first times of social distancing, the group decided to further explore experiments between theater and audiovisual realms, incorporating elements from visagism, Commedia dell’arte and cenic movement expression, using methods from Stanislavsky, Brecht and Grotowski. They have presented through Sympla their creation O bardo sem filtro (or, The bard without filters), which is a humorous performance based on The taming of the shrew, Love’s labor’s lost, Much ado about nothing and All’s well that ends well. It places emphasis on the comic exchanges and situations of the plays, all of which had been performed by the group before (that is, on regular in-person stages), and the dialogues tend to use Portuguese in a contemporary fashion for better understanding. Something to highlight in this production is the technique of image fusion through chroma key, a decision by the director to create the illusion that the actors really share the scene (since each is in his or her own home).

O bardo sem filtro

This mapping of Brazilian creations related to Shakespeare during the pandemic could not end without talking about Cena IV – Shakespeare Cia. The famous and awarded group works toward democratizing access to art and culture. They have a lasting partnership with Instituto Shakespeare Brasil to occupy plazas, metro stations, public squares, with the project “Um olhar brasileiro para Shakespeare” (or something like “A Brazilian view of Shakespeare”) and “Shakespeare para todos” (“Shakespeare for everyone”). With the pandemic time and the closure of theaters, Cena IV, Instituto Shakespeare Brasil and Irmãos Marin Produções created the project A web é um palco (or, The web is a stage), based on the previous, in-person creation, O mundo é um palco (The world is a stage). It consisted of excerpts broadcast weekly, particularly using accessible language and variable translations, of a variety of Shakespearean plays. It was a way to maintain not only the group functioning and creatively producing and acting, but also keep the idea and imagery of the long lasting show O mundo é um palco, focused on disseminating Shakespeare’s texts and legacy.

A web é um palco

The rich and varied group of creations presented here is indicative of a very active stage, online and offline, for Shakespeare in Brazil. Many other relevant productions were developed and could have been included in this text, but were not due to time and space constraints. Clearly, Shakespeare is widespread in Brazil and resists the challenges of the pandemic and its consequences – thanks to the passion and imagination of theater artists around here.

Author:

Aline de Mello Sanfelici – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

If you want to discuss or share about other Brazilian productions of Shakespeare during the pandemic, please contact me at: sanfelici@professores.utfpr.edu.br

[1] More of this account can be found, in Portuguese, here: https://g1.globo.com/pop-arte/noticia/2020/08/05/thiago-lacerda-comenta-experiencia-de-fazer-teatro-on-line-foi-muito-estranho-e-diferente.ghtml

[2] A similar initiative was a performance based on Romeo and Juliet in which the story is told from Rosalind’s perspective. The actress, famous for her participation in a popular comedy troupe, Júlia Rabello, acts in an empty auditorium with live transmission to Youtube and Facebook. The show was called Romeu e Julieta (e Rosalina), and emphasized comic aspects and feminist themes.

[3] Data from https://www.consumidormoderno.com.br/2021/07/23/podcasts-modelo-pandemia-brasil/, accessed in July 2022.