Even though Shakespeare has been regarded as an “English” playwright, characters in his plays hail from the Mediterranean, Cataian (Cathay), France, Vienna, Venice, and beyond. Global cultures play an important role even in the history plays that focus on the question of English identity. Nevertheless, Shakespeare and global studies remain strange bedfellows due to conventional disciplinary siloes.

We can use a site-specific lens to examine Shakespeare and global cultures, bringing together methodologies of dramaturgy, film and performance studies, and critical race and gender studies. One of the analytical tools we can use is the notion of penumbra. When light is shed over an opaque object, it casts a shadow with a partially shaded outer region. In terms of adaptation, this penumbra could be extra-textual information–information not contained within Shakespeare’s plays but is closely associated with the adaptations. The penumbra enriches the meanings of the adaptations. An innocuous penumbra could be audiences’ awareness of previous works by the artist. A more intrusive penumbra could be directors’ statements on record or the significance of the venue.

Here are some adaptations that share important themes in common even though they seem to bear different cultural coordinates at first blush. They form a global penumbra of multiple cultural texts as they evoke discrete plot elements of Shakespeare and culturally-specific themes.

Some of these examples bill themselves as Shakespearean adaptations, while others do not advertise any clear artistic relationship with Shakespeare.

Belonging to the first type – works that acknowledge Shakespeare’s plays as their sources – is the whodunit thriller The Hungry (dir. Bornila Chatterjee, 2017). The film markets itself as an Indian interpretation of Shakespeare. The adaptation of Titus Andronicus takes place almost entirely within the walls of the private estate of a business tycoon named Tathagat Ahuja (Naseeruddin Shah) in contemporary New Delhi.

The film builds toward a gory dénouement, a wedding feast where the vengeful widow Tulsi Joshi (Tisca Chopra) meets Tathagat’s cruelty, with a menu featuring human flesh. Tathagat, depicted as fond of the culinary art, tells the couple “I have made a feast with my own hands” as he welcomes them into the banquet hall. The camera lingers on close-up shots of the couple’s mouths and how they lick their fingers. Bent on revenge for the murder of her son, Tulsi ends up being killed herself.

Feasting becomes an act driven by animalistic desires. After all of the characters are killed, a group of black goats wander into the banquet hall to devour what is left on the table and to cleanse the sins. The grotesque gives way to a cyclical process of natural turnover.

The second type of works – those with “attenuated” references to Shakespeare – include the Saudi film Barakah Meets Barakah (2016), a rare romantic comedy film from Saudi Arabia. Drawing on Hamlet’s tentative relationship to his love interest, Ophelia, the film portrays the relationship between Barakah (Hisham Fageeh), a middle-class bureaucrat, and Barakah (Fatima Al Banawi), a feminist fashion vlogger. The pair struggles against strict conventions of their society.

When he is not working, the male Barakah performs as part of an amateur theatre troupe. In one scene, unable to find women to participate in their production, Barakah’s troupe had him play Ophelia. He appears in drag, thickly bearded. Instead of embracing his stage role, Barakah looks dejected in his blonde wig and green teal ball gown. His chest hair pokes out of his faux Elizabethan bodice. In an earlier scene, backstage, he strains to zip up the costume, and he is coached on how to simulate having breasts.

Barakah plays the “mad” Ophelia stiffly in a monotone: “They bore him barefaced on the bier, and in his grave rain’d many a tear.” The scene serves both as comic relief and a sober reminder of Saudi law that prohibits women from performing with men. The camera – with a frontal shot with deep focus – follows Barakah as he moves laterally on a small stage handing out flowers, telling an off-camera audience: “That’s for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember.”

Improvising and interspersing the otherwise stylized lines with modern language, he continues stage right: “And you, take this, I would give you some violets, but they withered all when he died.” Barakah, inspired by his involvement in theatre, has a dream in which he plays Hamlet alongside his lover who plays Ophelia.

Whereas The Hungry are designed and billed as adaptations of Shakespeare, Barakah Meets Barakah has not been recognized even as having any relationship to Hamlet, and has not circulated widely outside Saudi Arabia.

Some attenuated allusions to Shakespeare are more fleeting and decontextualized from the plays’ penumbra, even though these instances of mise en abyme do attest to Shakespeare’s global reach in our times across many media. In fact, attenuated allusions to Shakespeare have appeared frequently in globally high-profile films over the past decades, sometimes as hidden messages known as “Easter eggs” in the film industry.

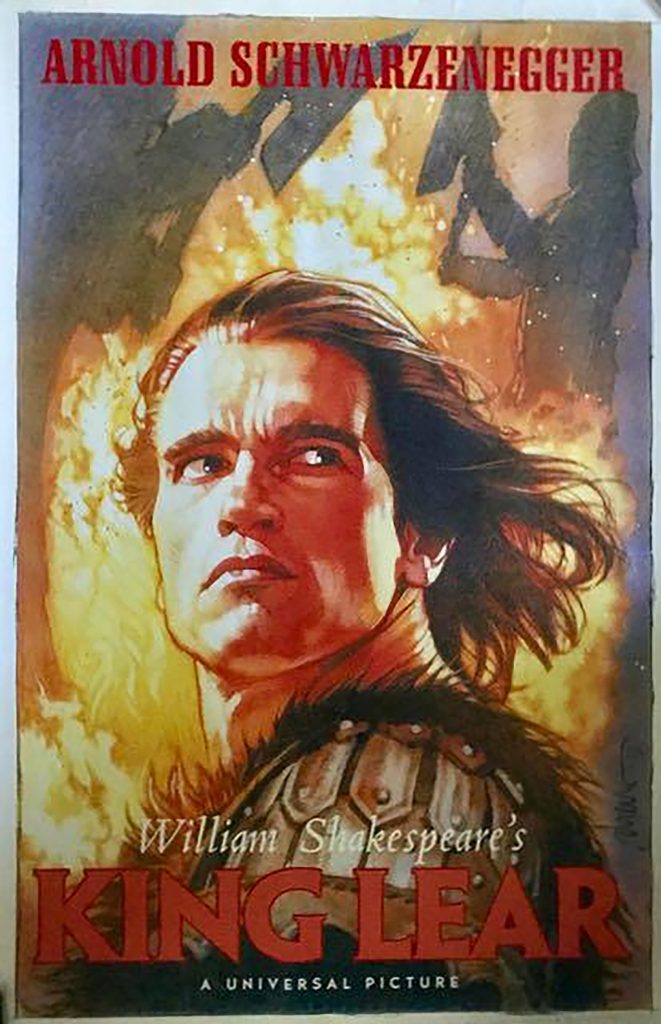

Arnold Schwarzenegger makes a cameo appearance as King Lear in Steven Spielberg’s science fiction film The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). Schwarzenegger’s Lear appears against a backdrop of raging fire on a poster. The caption says: “William Shakespeare’s King Lear.” This poster is designed by legendary illustrator Drew Struzan.

ilm audiences catch a glimpse of the Lear poster in a video store before a dinosaur sends a bus to crash into it. Spielberg’s film uses the presence of Shakespeare as vestiges of human civilization. That civilization – condensed in the films in this video store, including a fictional Lear film – is subsequently destroyed by dinosaurs that run amok.

Schwarzenegger’s cameo here pays tribute to his performance of Hamlet in John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero in 1993. When an English teacher screens Laurence Olivier’s film Hamlet (1948) in class, a daydreaming school boy imagines Hamlet as an action film starring his favorite action hero Jack Slater (Schwarzenegger). In an uncanny moment, Schwarzenegger’s Terminator-esque Slater wears Olivier’s costumes and holds a rifle. He does not hesitate to kill other characters in Hamlet, and always has a straightforward answer to such questions as “To be, or not to be?” as he blows up his enemies.

While in the 1990s audiences typically encountered Shakespeare for the first time through film or theatre, in our times the initial encounters occur predominantly on digital platforms in the form of video clips, memes or quotes. It has become more common for non-professional readers and audiences to encounter global Shakespeares in fragmented forms, such as the Ophelia scene in Barakah Meets Barakah.

To further our understanding of Shakespeare in the post-pandemic era, it is important to use global studies methodologies to engage with the hybrid cultural themes that inform many adaptations.

===========================

Excerpted from Alexa Alice Joubin, “Uncomfortable Bedfellows: Shakespeare and Global Studies,” Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 40 (2022), doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare.7040

Click here for the open-access full text