Opening sequence: the grand entry (0:01:11)

Opening sequence: the grand entry (0:01:11)

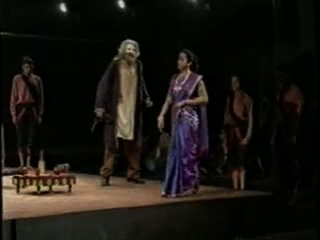

Lear’s speech to his daughters (0:00:18)

Lear’s speech to his daughters (0:00:18)

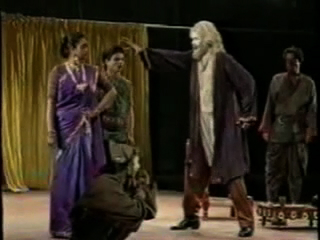

Goneril’s ritualistic flattery (0:01:08)

Goneril’s ritualistic flattery (0:01:08)

Artful Regan (0:00:27)

Artful Regan (0:00:27)

Cordelia’s “nothing” (00:01:00)

Cordelia’s “nothing” (00:01:00)

Cordelia’s truth (0:00:50)

Cordelia’s truth (0:00:50)

Lear’s curse (0:00:41)

Lear’s curse (0:00:41)

France proposes to Cordelia (0:00:33)

France proposes to Cordelia (0:00:33)

Goneril and Regan confer (0:01:09)

Goneril and Regan confer (0:01:09)

Edmund’s soliloquy (0:00:42)

Edmund’s soliloquy (0:00:42)

Goneril’s impatience (0:00:17)

Goneril’s impatience (0:00:17)

Lear’s ritual preparation for a meal (0:01:59)

Lear’s ritual preparation for a meal (0:01:59)

Oswald’s “slack” (0:00:13)

Oswald’s “slack” (0:00:13)

The Fool caps Kent (0:01:04)

The Fool caps Kent (0:01:04)

The Fool’s wit in song (0:00:24)

The Fool’s wit in song (0:00:24)

Goneril and Lear clash (0:00:55)

Goneril and Lear clash (0:00:55)

Goneril criticizes, the Knights protest (0:01:03)

Goneril criticizes, the Knights protest (0:01:03)

Lear curses Goneril (0:00:22)

Lear curses Goneril (0:00:22)

Kent roughs up Oswald (0:01:18)

Kent roughs up Oswald (0:01:18)

Final blow: “What need one?” (0:00:43)

Final blow: “What need one?” (0:00:43)

Grief and rage at his rejection (0:00:24)

Grief and rage at his rejection (0:00:24)

Premonition of madness (0:01:04)

Premonition of madness (0:01:04)

Storm scene (00:00:43)

Storm scene (00:00:43)

Rage turns to self-pity (0:00:06)

Rage turns to self-pity (0:00:06)

Remembers the Fool (0:00:56)

Remembers the Fool (0:00:56)

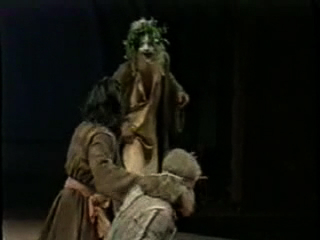

Poor Tom (0:01:14)

Poor Tom (0:01:14)

Unaccommodated man (0:00:02)

Unaccommodated man (0:00:02)

The mock trial (0:00:34)

The mock trial (0:00:34)

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard (0:00:31)

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard (0:00:31)

The blinding of Gloucester (0:00:57)

The blinding of Gloucester (0:00:57)

The servant’s challenge (0:00:27)

The servant’s challenge (0:00:27)

Regan turns her back on Cornwall (0:00:27)

Regan turns her back on Cornwall (0:00:27)

Gloucester and Poor Tom (0:01:08)

Gloucester and Poor Tom (0:01:08)

Goneril gives a token to Edmund (0:01:13)

Goneril gives a token to Edmund (0:01:13)

Regan tries to manipulate Oswald (0:00:11)

Regan tries to manipulate Oswald (0:00:11)

Gloucester and Edgar in Dover (0:00:30)

Gloucester and Edgar in Dover (0:00:30)

Gloucester’s suicide (0:01:08)

Gloucester’s suicide (0:01:08)

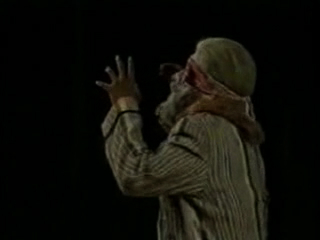

“Mad” Lear (0:00:04)

“Mad” Lear (0:00:04)

Handy-dandy wisdom (0:00:33)

Handy-dandy wisdom (0:00:33)

Self-recognition in the world of fools (0:01:16)

Self-recognition in the world of fools (0:01:16)

Lear asleep (0:01:10)

Lear asleep (0:01:10)

Lear reborn (0:00:29)

Lear reborn (0:00:29)

Lear contrite (0:00:14)

Lear contrite (0:00:14)

Lear begs forgiveness (0:00:06)

Lear begs forgiveness (0:00:06)

Edmund’s soliloquy (0:00:39)

Edmund’s soliloquy (0:00:39)

Battle scenes (0:00:27)

Battle scenes (0:00:27)

Lear welcomes imprisonment with Cordelia (0:01:43)

Lear welcomes imprisonment with Cordelia (0:01:43)

Regan and Goneril squabble over Edmund (0:00:47)

Regan and Goneril squabble over Edmund (0:00:47)

Edgar’s challenge (0:00:51)

Edgar’s challenge (0:00:51)

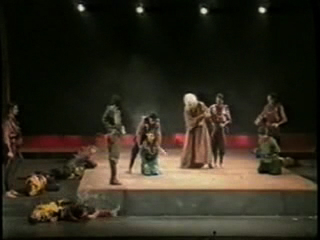

Lear with the dead Cordelia (0:00:25)

Lear with the dead Cordelia (0:00:25)

The recognition of Kent (0:01:12)

The recognition of Kent (0:01:12)

Death of Lear (0:00:30)

Death of Lear (0:00:30)

About This Clip

Samrat Lear (King Lear)

Samrat Lear, a March 1997 Hindi-language adaptation of King Lear by the National School of Drama in New Delhi. Directed by John R. Brown from a script by Harivansh Rai Bachchan.

Read more about the “localized Shakespeare” performance style.

Cast

Lear – Chetan Pandit

Goneril – S. Shameem

Regan – Megha Malik

Cordelia – Sunita Chand Rajwar

Albany – Sanjay Kumar

Cornwall – Hrishikesh Joshi

France – Firoz Zahidkhan

Burgundy – Moloy Ghose

Kent – Rajiv Kumar

Gloucester – Ashraful Haque

Edgar – Dibyendu Bhattacharya

Edmund – Manohar Teli

Oswald – Moloy Ghose

Fool – Manoj Goyal

First Knight – Rajpal Singh Yadav

Curan – Noushad Mohamed

Old Man – Mohamed Ashique Hussain

Doctor – Hrishikesh Joshi

Herald – Moloy Ghose

Performers were Third Year Students at the National School of Drama (New Delhi, India). First performance took place at the National School of Drama’s indoor auditorium, Abhimanch, New Delhi, India.

Samrat Lear (King Lear)

Clips

The recognition of Kent

Lear: This’ a dull sight. Are you not Kent? Kent: The same; Your servant Kent. Where is your servant Caius? Lear: He’s a good fellow, I can tell you that;...more

Lear: This’ a dull sight. Are you not Kent?

Kent: The same;

Your servant Kent. Where is your servant Caius?

Lear: He’s a good fellow, I can tell you that;

He’ll strike, and quickly too. He’s dead and rotten.

Kent: No, my good lord; I am the very man-

(V.iii.282 – 286)

The recognition of Kent, a sequence often edited out of performances, eg. in Raja Lear and of course in Iruthiattam. less

Death of Lear

Lear: And my poor fool is hang’d! No, no, no life! Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life. And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come no...more

Lear: And my poor fool is hang’d! No, no, no life!

Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life.

And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come no more,

Never, never, never, never, never!

Pray you undo this button. Thank you, Sir.

Do you see this? Look on her! look! her lips!

Look there, look there! [Dies].

Edg: He faints! My lord, my Lord!

Kent: Break, hear; I prithee, break!

Edg: Look up, my Lord.

Kent: Vex not his ghost: O! let Him pass; he hates him

That would upon the rack of this tough world

Stretch him out longer.

Edg: He is gone, indeed. (V.iii.305 – 315)

The last hope: Lear imagines Cordelia speaks; that breath stirs in her and, overcome by this, dies. The more than usual emphasis on the “thank you, Sir” to the one that undoes his button becomes a touchstone of the journey Lear has traversed – the recognition of the services of the others. less

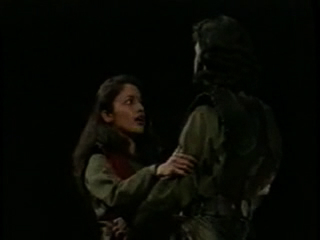

Lear begs forgiveness

Cor: Will ‘t please your Highness walk? Lear: You must bear with me. Pray you now, forget and forgive. I am old and foolish. [Exeunt Kent, Cordelia, Doctor, and Attendants]....more

Cor: Will ‘t please your Highness walk?

Lear: You must bear with me.

Pray you now, forget and forgive. I am old and foolish.

[Exeunt Kent, Cordelia, Doctor, and Attendants].

(IV.vii.183 – 184)

Mustering the strength to standup, he cannot begin to walk, resume ‘normal’ activity until he has begged forgiveness of Cordelia. This reconciliation scene, in Raja Lear, with its mood lighting seems to communicate more deeply felt emotion. Iruthiattam, on the other hand, achieves a heightened intensity with its expressionistic stylization and a telescoping of scenes. Note the Buddhist chant that begins as the actors walk out signifying peace at last. less

Edmund’s soliloquy

Edm: To both these sisters have I sworn my love; Each jealous of the other, as the stung Are of the adder. Which of them shall I take? Both? one?...more

Edm: To both these sisters have I sworn my love;

Each jealous of the other, as the stung

Are of the adder. Which of them shall I take?

Both? one? or neither? Neither can be enjoy’d,

If both remain alive. To take the widow

Exasperates, makes mad her sister Goneril;

And hardly shall I carry out my side,

Her husband being alive. Now then, we’ll use

His countenance for the battle, which being done,

Let her who would be rid of him devise

His speedy taking off. As for the mercy

Which he intends to Lear and to Cordelia-

The battle done, and they within our power,

Shall never see his pardon; for my state

Stands on me to defend, not to debate.

(V.i.55 – 69)

Edmund’s soliloquy, relishing the prospect that both the sisters are squabbling over him. Spoken out to the audience his speech has insouciance, born out of his ‘natural’ lowness/ villainy. less

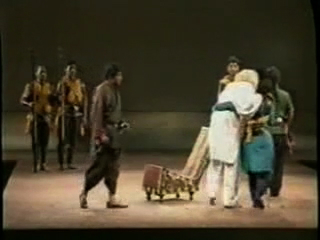

Battle scenes

Battle scenes (V.ii) Battle scenes: the violence of the power struggle was emphasized in this production by several scenes of armed confrontation, again presented realistically with bugle calls, long sword...more

Battle scenes (V.ii)

Battle scenes: the violence of the power struggle was emphasized in this production by several scenes of armed confrontation, again presented realistically with bugle calls, long sword fights, corpses on the stage, and smoke curling from burning embers of the battlefield. Note the floor a symbolic blood-shot red. less

Lear welcomes imprisonment with Cordelia

Lear: No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison; We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage: When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down, And...more

Lear: No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison;

We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; (V.iii.8 – 14)

Lear refuses to petition his elder daughters for his release. Instead, together with Cordelia, he insists, they will enjoy another freedom, of togetherness! Together with Cordelia he feels he is in a blessed state. An assertion of the old confidence. less

Regan and Goneril squabble over Edmund

Reg: That’s as we list to grace him; Methinks our pleasure might have been demanded, Ere you had spoke so far. He led our powers, Bore the commission of my...more

Reg: That’s as we list to grace him;

Methinks our pleasure might have been demanded,

Ere you had spoke so far. He led our powers,

Bore the commission of my place and person,

The which immediacy may well stand up,

And call itself your brother.

Gon: Not so hot!

In his own grace he doth exalt himself

More than in your addition.

Reg: In my rights

By me invested, he compeers the best.

Alb: That were the most if he should husband you.

Reg: Jesters do oft prove prophets.

Gon: Holla, holla!

That eye that told you so look’d but a- squint.

Reg: Lady, I am not well; else I should answer

From a full-flowing stomach. General,

Take thou my soldiers, prisoners, patrimony;

Dispose of them, of me; the walls are thine.

Witness the world that I create thee here

My lord and master.

Gon: Mean you to enjoy him?

Alb: The let-alone lies not in your good will.

Edm: Nor in thine, lord.

Alb: Half-blooded fellow, yes.

Reg: [to Edmund] Let the drum strike, and

prove my title thine.

Alb: Stay yet; hear reason. Edmund, I arrest thee

On capital treason; and, in thy attaint,

This gilded serpent. [Pointing to Goneril].

For your claim, fair sister,

I bar it in the interest of my wife.

‘Tis she is subcontracted to this lord,

And I, her husband, contradict your banes.

If you will marry, make your loves to me;

My lady is bespoke. (V.iii.62 – 90)

Goneril and Regan squabble over Edmund, both vying for alliance with him. less

Edgar’s challenge

Edg: Draw thy sword, That, if my speech offend a noble heart, Thy arm may do thee justice; here is mine. Behold, it is the privilege of mine honours, My...more

Edg: Draw thy sword,

That, if my speech offend a noble heart,

Thy arm may do thee justice; here is mine.

Behold, it is the privilege of mine honours,

My oath, and my professtion: I protest,

Maugre thy strenth, youth, place and eminence,

Despite they victor sword and fire-new fortune,

Thy valour and thy heart, thou art a traitor;

False to thy gods, thy brother, and thy father;

Conspirant ‘gainst this high illustrious prince;

And, from th’ extremest upward of thy head

To the descent and dust beneath thy foot,

A most toad-spotted traitor. Say thou ‘No,’

This sword, this arm, and my best spirits are bent

To prove upon thy heart, whereto I speak,

Thou liest.

Edm: In wisdom I should ask thy name;

But, since thy outside looks so fair and war-like,

And that thy tongue some say of breeding breathes,

What safe and nicely I might well delay

By rule of knighthood, I disdain and spurn;

Back do I toss those treason to thy head,

With the hell-hated lie o’erwhelm thy heart,

Which, for they yet glance by and scarcely bruise,

This sword of mine shall give them instant way,

Where they shall rest for ever. Trumpets, speak!

[Alarums. They fight. Edmund falls.] (V.iii.127 – 150)

Edgar’s challenge to Edmund, and then the duel. The sword fighting in the production is based on Manipuri martial art and technique. less

Lear with the dead Cordelia

Re-enter Lear, with Cordelia dead in his arms; Officer. Lear: Howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones: Had I your tongues and eyes, I’ld use them so That...more

Re-enter Lear, with Cordelia dead in his arms; Officer.

Lear: Howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones:

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’ld use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone for ever.

I know when one is dead, and when one lives;

She’s dead as earth. Lend me a looking glass;

If that her breath will mist or stain the stone,

Why, then she lives. (V.iii.257 – 263)

Lear enters with the dead Cordelia in his arms. The lack of special lighting and the backdrop of the battle field makes Cordelia’s death a part of the destruction of the long power struggle, shifting the emphasis from an individualised tragedy. less

“Mad” Lear

Glou: Is’t not the King? Lear: Ay, every inch a king! When I do stare, see how the subject quakes. I pardon that man’s life. What was thy cause? Adultery?...more

Glou: Is’t not the King?

Lear: Ay, every inch a king!

When I do stare, see how the subject quakes.

I pardon that man’s life. What was thy cause?

Adultery?

Thou shalt not die. Die for adultery? No.

The wren goes to’t, and the small gilded fly

Does lecher in my sight.

Let copulation thrive; for Gloucester’s bastard son

Was kinder to his father than my daughters

Got ‘tween the lawful sheets. To’t, Luxury, pell-mell!

For I lack soldiers. (IV.vi.110 – 120)

Lear in his mad regalia – with a coronet of weeds and wild flowers. Again, in his costume and gestures, “mad” Lear was localised in a familiar, physicalised manner. less

Handy-dandy wisdom

Glou: O, let me kiss that hand! Lear: Let me wipe it first; it smells of mortality. Glou: O ruin’d piece of Nature! This great world Shall so wear out...more

Glou: O, let me kiss that hand!

Lear: Let me wipe it first; it smells of mortality.

Glou: O ruin’d piece of Nature! This great world

Shall so wear out to naught. Dost thou know me?

Lear: I remember thine eyes well enough. Does

thou squiny at me?

No, do thy worst, blind Cupid! I’ll not love.

Read thou this challenge; mark but the penning of it.

Glou: Were thy letters suns, I could not see.

Edg: [Aside.] I would not take this from report; it is,

And my heart breaks at it.

Lear: Read.

Glou: What! With the case of eyes?

Lear: O, Ho! Are you there with me? No eyes in

your head, nor no money in your purse?

Your eyes are in a heavy case, your

purse in a light: yet you see how this

world goes.

Glou: I see it feelingly.

Lear: What! art mad? A man may see how the

world goes with no eyes. Look with

thine eyes. See how yond justice rails

upon yond simple thief. Hark in thine

ear. Change places and, handy-dandy,

which is the justice, which is the thief. (IV.vi.134 – 155)

The clarity of madness: Gloucester recognizes Lear’s voice and wishes to kiss the King’s hand; Lear who has suffered the ague of ignominy, insists on wiping his hand first! Irony: Lear acquires wisdom in witlessness; he can now see through the image of Authority and Justice, and how the judge is often as guilty as the thief. less

Self-recognition in the world of fools

Lear: I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester. Thou must be patient; we came crying hither: Thou know’st, the first time that we smell the air We wawl...more

Lear: I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester.

Thou must be patient; we came crying hither:

Thou know’st, the first time that we smell the air

We wawl and cry. I will preach to thee: mark.

Glou: Alack, alack the day!

Lear: When we are born, we cry that we are come

To this great stage of fools. This’ a good block! (IV.vi.179 – 185)

Pathos and self-mockery in the realization of the irony of life in a world peopled by fools. less

Lear asleep

Cor: O my dear father, restoration hang Thy medicine on my lips, and let this kiss Repair those violent harms that my two sisters Have in thy reverence made! Kent:...more

Cor: O my dear father, restoration hang

Thy medicine on my lips, and let this kiss

Repair those violent harms that my two sisters

Have in thy reverence made!

Kent: Kind and dear princess!

Cor: Had you not been their father, these white flakes

Did challenge pity of them. Was this a face

To be oppos’d against the warring winds?

To stand against the deep dread-bolted thunder?

In the most terrible and nimble stroke

Of quick cross lightning? to watch- poor perdu!-

With this thin helm? Mine enemy’s dog,

Though he had bit me, should have stood that night

Against my fire; and wast thou fain, poor father,

To hovel thee with swine and rogues forlorn,

In short and musty straw? Alack, alack!

‘Tis wonder that thy life and wits at once

Had not concluded all. He wakes; speak to him.

(IV.vii.26 – 42)

Lear is brought in asleep and Cordelia weeps at the pathos of the situation. less

Lear reborn

Lear: Pray, do not mock me. I am a very foolish fond old man, Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less; And, to deal plainly, I fear I...more

Lear: Pray, do not mock me.

I am a very foolish fond old man,

Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less;

And, to deal plainly,

I fear I am not in my perfect mind.

Methinks I should know you, and know this man;

Yet, I am doubtful: for I am mainly ignorant

What place this is, and all the skill I have

Remembers not these garments; nor I know not

Where I did lodge last night. Do not laught at me;

For (as I am a man) I think this lady

To be my child Cordelia.

Cor: And so I am! I am! (IV.vii.59 – 70)

Lear reborn: he awakes into a new understanding of himself, slowly recognizing his daughter Cordelia. less

Lear contrite

Lear: Be your tears wet? Yes, faith. I pray weep not; If you have poison for me, I will drink it. I know you do not love me; for your...more

Lear: Be your tears wet? Yes, faith. I pray weep not;

If you have poison for me, I will drink it.

I know you do not love me; for your sisters

Have, as I do remember, done me wrong.

You have some cause, they have not.

Cor: No cause, no cause. (IV.vii.72 – 75)

Deeply contrite, Lear kneels to Cordelia. less

The servant’s challenge

1.Serv: Hold your hand, my lord! I have serv’d you ever since I was a child But better service have I never done you Than now to bid you hold....more

1.Serv: Hold your hand, my lord!

I have serv’d you ever since I was a child

But better service have I never done you

Than now to bid you hold.

Reg: How now, you dog?

1.Serv: If you did wear a beard upon your chin,

I’ld shake it on this quarrel.

Reg: What do you mean?

Corn: My villain! [Draw and fight.]

1.Serv: Nay, then, come on, and take the

chance of anger.

Reg: Give me thy sword. A peasant stand up thus!

[Takes a sword and runs at him behind.]

1.Serv: O, I am slain! My lord, you have one eye left

To see some mischief on him. Oh! [Dies.] (III.vii.72 – 81)

The challenge of the servant: a servant who protests at the injustice towards Gloucester redeems the inhumanity of the play, briefly. He is counter challenged to a duel by Cornwall but is killed by Regan who stabs him in the back. less

Regan turns her back on Cornwall

Corn: Regan, I bleed apace. Untimely comes this hurt. Give me your arm. [Exit Cornwall, let by Regan] (III.vii.96 – 97) Cornwall wounded, but Regan, in contrast to her seeming...more

Corn: Regan, I bleed apace.

Untimely comes this hurt. Give me your arm.

[Exit Cornwall, let by Regan] (III.vii.96 – 97)

Cornwall wounded, but Regan, in contrast to her seeming affection for him a few minutes earlier, does not move to comfort him and, unlike in the original text, walks away in the opposite direction with a calculating glint in her eye. The critical comments of the other servants were deleted. less

Gloucester and Poor Tom

Glou: Know’st thou the way to Dover? Edg: Both stile and gate, horse-way and foot- path. Poor Tom hath been scar’d out of his good wits; bless thee, good man’s...more

Glou: Know’st thou the way to Dover?

Edg: Both stile and gate, horse-way and foot-

path. Poor Tom hath been scar’d out of

his good wits; bless thee, good man’s

son, from the foul fiend! Five fiends have

been in poor Tom at once; as Obidicut of

lust; Hoberdidance, prince of dumbness;

Mahu, of stealing; Modo, of murder;

Flibbertigibbet, of mopping and mowing;

who since possesses chambermaids and

waiting women. So, bless thee, master!

Glou: Here, take this Purse, thou whom the heavens’ plagues

Have humbled to all strokes: that I am wretched

Makes thee the happier: Heavens, deal so still!

Let the superfluous and lust-dieted man,

That slaves your ordinance, that will not see

Because he does not feel, feel your power quickly;

So distribution should undo excess,

And each man have enough. Dost thou know Dover?

(IV.i.54 – 71)

Gloucester with Poor Tom, asking him to lead him to Dover. less

Goneril gives a token to Edmund

Gon: Back, Edmund, to my brother; Hasten his musters and conduct his powers: I must change arms at home, and give the distaff Into my husband’s hands. This treaty servant...more

Gon: Back, Edmund, to my brother;

Hasten his musters and conduct his powers:

I must change arms at home, and give the distaff

Into my husband’s hands. This treaty servant

Shall pass between us; ere long you are like to hear,

If you dare venture in your own behalf,

A mistress’s command. Wear this; spare speech;

[Gives a favour.]

Decline your head: this kiss, if it durst speak,

Would stretch thy spirits up into the air.

Conceive, and fare thee well.

Edm: Yours in the ranks of death.

Gon: My most dear Gloucester! [Exit Edmund]

O, the difference of man and man!

To thee a woman’s services are due:

My Fool usurps my body. (IV.ii.15 – 28)

Goneril gives a token to Edmund making her sexual interest in him quite evident. Again, it was part of the realism of this staging to let the lust and viciousness of the sisters directly express itself. An interesting instance of Oswald’s sycophancy – he looks away when his mistress kisses her token before giving it to Edmund! less

Regan tries to manipulate Oswald

Reg: Our troops set forth to-morrow. Stay with us. The ways are dangerous. Osw: I may not, Madam. My lady charg’d my duty in this business. Reg: Why should she...more

Reg: Our troops set forth to-morrow. Stay with us.

The ways are dangerous.

Osw: I may not, Madam.

My lady charg’d my duty in this business.

Reg: Why should she write to Edmund? Might not you

Transport her purposes by word? Belike,

Some things–I know not what. I’ll love thee much-

Let me unseal the letter.

Osw: Madam, I had rather-

Reg: I know your lady does not love her husband;

I am sure of that: and at her late being here

She gave strange eilliads and most speaking looks

To noble Edmund. I know you are of her bosom.

Osw: I, Madam!

Reg: I speak in understanding; y’are, I know’t:

Therefore I do advise you, take this note:

My lord is dead; Edmund and I have talk’d,

And more convenient is he for my hand

Than for your Lady’s. You may gather more.

If you do find him, pray you give him this;

And when your mistress hears thus much from you,

I pray desire her call her wisdom to her:

So fare you well.

If you do chance to hear of that blind traitor,

Preferment falls on him that cuts off.

Osw: Would I could meet, Madam: I should show

What Party I do follow.

Reg: Fare thee well. (IV.v.16 – 40)

Regan and Oswald: Regan’s manipulation knows no bounds; she will scheme against her sister. Regan tries to get at Goneril’s letter to Edmund, which is being carried by Oswald. She offers him a big reward for the capture of Gloucester, part of her ploy to buy over Oswald. The obsequious fool Oswald’s face lights up at the mention of money and he exits promising to work for Regan. less

Gloucester and Edgar in Dover

Edg: Come on, sir; here’s the place: stand still. How fearful And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low! The crows and choughs that wing the midway air Show...more

Edg: Come on, sir; here’s the place: stand still.

How fearful

And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low!

The crows and choughs that wing the midway air

Show scarce so gross as beetles; half way down

Hangs one that gathers sampire, dreadful trade

Methinks he seems no bigger than his head.

The fishermen that walk upon the beach

Appear like mice, and yond tall anchoring bark

Diminish’d to her cock, her cock, a buoy

Almost too small for sight. The murmuring surge,

That on th’ unnumber’d idle pebble chafes,

Cannot be heard so high. I’ll look no more,

Lest my brain turn, and the deficient sight

Topple down headlong.

Glou: Set me where you stand.

Edg: Give me your hand; you are not within a foot

Of th’ extreme verge: for all beneath the moon

Would I not leap upright.

Glou: Let go my hand.

Here, friend, ‘s another purse; in it a jewel

Well worth a poor man’s taking: fairies and Gods

Prosper it with thee! Go thou further off;

Bid me farewell, and let me hear thee going.

Edg: Now fare ye well, good sir.

Glou: With all my heart. (IV.vi.11 – 33)

Gloucester and Edgar on the cliff of Dover. Edgar looks down, positions Gloucester on the so-called edge, while Gloucester gives him a purse, preparing to die. Note the blue cyclorama, the shimmering waters and the streak of white of the chalk cliffs, presenting humans dwarfed in a world on the edge of eternity. less

Gloucester’s suicide

Glou: Now, fellow, fare thee well. [He throws himself forward and fall] (IV.vi.42) Gloucester’s suicide: here he falls backwards, a gesture slightly less bathetic than the front flop.more

Glou: Now, fellow, fare thee well.

[He throws himself forward and fall]

(IV.vi.42)

Gloucester’s suicide: here he falls backwards, a gesture slightly less bathetic than the front flop. less

Rage turns to self-pity

Lear: I am a man More sinn’d against than sinning. (III.ii.58 – 59) Rage turns to self-pity: “More sinned against than sinningmore

Lear: I am a man

More sinn’d against than sinning. (III.ii.58 – 59)

Rage turns to self-pity: “More sinned against than sinning less

Remembers the Fool

Lear: How dost, my boy? Art cold? I am cold myself. Where is this straw, my fellow? The art of our necessities is strange, That can make vile things precious....more

Lear: How dost, my boy? Art cold?

I am cold myself. Where is this straw, my fellow?

The art of our necessities is strange,

That can make vile things precious.

Come, your hovel.

Poor fool and knave, I have one part in my heart

That’s sorry yet for thee.

Fool: [sings]

He that has and a little tiny wit,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

Must make content with his fortunes fit,

For the rain it raineth every day.

Lear: True, boy. Come, bring us to this hovel.

[Exeunt Lear and Kent.] (III.ii.68 – 78)

Battered by the storm, the monstrous ego of Lear is at last, cognisant of others. He sees the Fool shivering in the storm, turns to cover him with same wrap that has just been put on his own shoulders by Kent, then sits down in front of the Fool who sings to him another song of worldly wise advice in return. Note the traditional folk tune of the Fool’s song. less

Poor Tom

Edg: Take heed o’ th’ foul fiend; Obey thy parents: keep thy word’s justice; swear not; commit not with man’s sworn spouse; set not thy sweet heart on proud array....more

Edg: Take heed o’ th’ foul fiend; Obey thy

parents: keep thy word’s justice; swear

not; commit not with man’s sworn

spouse; set not thy sweet heart

on proud array. Tom’s a-cols.

Lear: What hast thou been?

Edg: A servingman, proud in heart and mind;

that curl’d my hair, wore gloves in

my cap, serv’d the lust of my mistress’

heart and did the act of darkness

with her; swore as many oaths as I

spake words, and broke them in the

sweet face of Heaven; one that slept in

the contriving of lust, and wak’d to

do it. Wine lov’d I deeply, dice dearly,

and in woman out-paramour’d the

Turk: false of heart, light of ear, bloody o

hand; hog insloth, fox in stealth,

wolf in greediness, dog in madness, lion

in prey. Let know the creaking of

shoes nor the rustling of silks betray thy

poor heart to woman: keep thy foot

out of brothels, thy hand out of plackets,

thy pen from lenders’ book, and

defy the foul fiend. Still through the

hawthorn blows the cold wind; says

suum, mun, hey no nonny. Dolphin my

boy, boy; sessa! let him trot by.

[Storm still] (III.iv.80 – 102)

Poor Tom is easily relocated and correlated with the well-known figure of the naked sadhu or ascetic who wears minimum clothing and covers his body with holy ask, keeps on the move and lives out in the open surviving on alms. Here he incorporates some fo the typical poses of penance, like standing on one leg. less

Unaccommodated man

Lear: Thou wert better in thy grave than to answer with thy uncover’d body this extremity of the skies. Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou ow’st...more

Lear: Thou wert better in thy grave than to

answer with thy uncover’d body this

extremity of the skies. Is man no

more than this? Consider him well. Thou

ow’st the worm no silk, the beast no

hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no

perfume. Ha! here’s three on’s are

sophisticated; thou art the thing

itself; unaccommodated man is no

more but such a poor, bare, forked

animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings!

Come, unbutton here.

[Tears at his clothes.]

Fool: Prithee, Nuncle, be contented; ’tis a

naughty night to swim in. (II.iv.104 – 114)

Lear, moved by the condition of Poor Tom, wants to identify with the poor nakes wretches who survive without the trappings of civilisation (clothes) by making a move to take off his own clothes. less

The mock trial

Lear: I’ll see their trial first. Bring in their evidence. [To Edgar.] Thou, robed man of justice, take thy place. [To the Fool.] And thou, his yokefellow of equity, Bench...more

Lear: I’ll see their trial first. Bring in their evidence.

[To Edgar.] Thou, robed man of justice, take thy place.

[To the Fool.] And thou, his yokefellow of equity,

Bench by his side. [To Kent] You are o’ th’ commission.

Sit you too.

Edg: Let us deal justly.

Sleepest or wakest thou, jolly shepard?

Thy sheep be in the corn;

And for one blast of thy minikin mouth

Thy sheep shall take no harm.

Purr! the cat is grey.

Lear: Arraign her first. ‘Tis Goneril. I here

take my oath before this honourable

assembly, she kicked the poor King her

father.

Fool: Come hither, mistress. Is your name Goneril?

Lear: She cannot deny it.

Fool: Cry you mercy, I took you for a joint-stool.

Lear: And here’s another, whose warp’d looks proclaim

What store her heart is made on. Stop her there!

Arms, arms! sword! fire! Corruption in the place!

False justicer, why hast thou let her scape?

Edg: Bless thy five wits!

Kent: O pity! Sir, where is the patience now

That you so oft have boasted to retain?

Edg: [aside] My tears begin to take his part so much,

They’ll mar my counterfeiting.

Lear: The little dogs and all,

Tray, Blanch, and Sweetheart, see, they bark at me.

Edg: Tom will throw his head at them.

Avaunt, you curs!

Be thy mouth or black or white,

Tooth that poisons if it bite;

Mastiff, greyhound, mongrel grim,

Hound or spaniel, brach or lym,

Or bobtail tike or trundle-tail;

Tom will make them weep and wail;

For, with throwing thus my head,

Dogs leap’d the hatch, and all are fled.

Do de, de, de. Sessa! Come, march to

wakes and fairs and market-towns. Poor

Tom, thy horn is dry.

Lear: Then let them anatomize Regan. See

what breeds about her heart.

Is there any cause in nature that makes

these hard hearts? (III.vi.34 – 79)

The mock trial in the hovel. The ethnic realism of the set is here seen in the hovel, designed after the commonly seen ‘lean-to’s or ubiquitous street shelters rigged up in shanty settlements in urban India. The text of this scene is lightly edited. This scene was cut in Raja Lear, so as not to reduce the King to an abject madness and the adaptation, Iruthiattam did not feel the need for this terrifying threesome. less

Regan plucks Gloucester’s beard

[Regan plucks his beard.] Glou: By the kind gods, ’tis most ignobly done To pluck me by the beard. Reg: So white, and such a traitor! (III.vii.34 – 37) The...more

To pluck me by the beard.

Reg: So white, and such a traitor! (III.vii.34 – 37)

The interrogation of Gloucester. Regan in her anger pulls at Gloucester’s beard but it surprised when it comes off in her fingers. Initially pleased with her spoils, she is then repulsed by it – a traitor’s beard – and flicks it off her fingers. Note the top lights giving a bleak white light suggestive of torture chambers. less

The blinding of Gloucester

Corn: See’t shalt thou never. Fellows, hold the chair. Upon these eyes of thine I’ll set my foot. Glou: He that will think to live till he be old, Give...more

Corn: See’t shalt thou never. Fellows, hold the chair.

Upon these eyes of thine I’ll set my foot.

Glou: He that will think to live till he be old,

Give me some help! O cruel! O ye gods!

Reg: One side will mock another; th’ other too!

Corn: If you see vengeance, — (III.vii.66 – 71)

The blinding of Gloucester, again realistically staged, emphasizing its cold-blooded brutality (“Almost too realistic for comfort,” The Statesman, 10 March 1997). Cornwall, in full view of the audience, uses his hands to pull out Gloucester’s eye, drops the eyeball on the floor, stubs it with his foot and then goes on to wipe his hands with a callous nonchalance. Regan now moves close to him, leaning on his shoulder, expressing her obvious relish in the gory violence just committed. In contrast, in Raja Lear, the blinding is staged with Cornwall’s back to the audience, blocking, and therefore, mediating, the brutality of the violence. In Iruthiattam this part of the sub-plot was edited out. less

Lear curses Goneril

Lear: Blasts and fogs upon thee! Th’ untented woundings of a father’s curse Pierce every sense about thee! Old fond eyes, Beweep this cause again, I’ll pluck ye out, And...more

Lear: Blasts and fogs upon thee!

Th’ untented woundings of a father’s curse

Pierce every sense about thee! Old fond eyes,

Beweep this cause again, I’ll pluck ye out,

And cast you, with the waters that you lose,

To temper clay. Yea, is it come to this?

Let it be so: I have another daughter, (1.iv.308 – 314)

Lear curses Goneril with barrenness, this time with another well-known gesture, of the extended hand with the fingers curved out towards the accursed person / victim, as if shooting shafts of venom outward, again deriving from the cursing sages of Indian mythology. less

Kent roughs up Oswald

Before Gloucester’s Castle Enter Kent and Oswald, severally. Osw: Good dawning to thee, friend: art of this house? Kent: Ay. Osw: Where may we set our horses? Kent: I’ th’...more

Before Gloucester’s Castle

Enter Kent and Oswald, severally.

Osw: Good dawning to thee, friend: art of this house?

Kent: Ay.

Osw: Where may we set our horses?

Kent: I’ th’ mire.

Osw: Prithee, if thou lov’st me, tell me.

Kent: I love thee not.

Osw: Why then, I care not for thee.

Kent: If I had thee in Lipsbuty Pinfold, I would

make thee care for me.

Osw: Why dost thou use me thus? I know thee not.

Kent: Fellow, I know thee.

Osw: What dost thou know me for?

Kent: A knave, a rascal; an eater of broken

meats; a base, proud, shallow, beggarly,

three-suited, hundred-pound, filthy,

worst-stocking knave; a lily-livered,

action-taking, whoreson, glass-gazing,

super-serviceable, finical rogue; one-

trunk-inheriting slave; one that wouldst

be a bawd in way of good service, and

art nothing but the composition of a

knave, beggar, coward, pandar, and the

son and heir of a mongrel bitch; one

whom I will beat into clamorous

whining, if thou deny the least syllable

of thy addition.

Osw: Why, what a monstrous fellow art thou,

thus to rail on one that’s neither known

of thee nor knows thee! (II.ii.1 – 26)

The Kent and Oswald encounter in the dark. Kent, the loyalist, is contemptuous of the young upstart, Oswald, who carries a brazen grin on his face. He roughs him up and Oswald shouts for help. Kent, quick to a fault, seems to be picking on Oswald and provoking him. less

Final blow: “What need one?”

Lear: [To Goneril] I’ll go with thee. Thy fifty yet doth double five-and-twenty, And thou art twice her love. Gon: Hear, me, my lord. What need you five-and-twenty, ten, or...more

Lear: [To Goneril] I’ll go with thee.

Thy fifty yet doth double five-and-twenty,

And thou art twice her love.

Gon: Hear, me, my lord.

What need you five-and-twenty, ten, or five,

To follow in a house where twice so many

Have a command to tend you?

Reg: What need one?

Lear: O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. Thou art a lady:

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st

Which scarcely keeps thee warm… (II.iv.259 – 272)

The final rejection and Lear’s shock and grief at being told by Regan “What need one?” less

Grief and rage at his rejection

Lear: You see me here, you Gods, a poor old man, As full of grief as age; wretched in both. If it be you that stirs these daughters’ hearts Against...more

Lear: You see me here, you Gods, a poor old man,

As full of grief as age; wretched in both.

If it be you that stirs these daughters’ hearts

Against their father, fool me not so much

To bear it tamely; touch me with noble anger,

And let not women’s weapons, water drops,

Stain my man’s cheeks! No, you unnatural hags!

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall–I will do such things,

What they are yet, I know not; but they shall be

The terrors of the earth! (II.iv.274 – 284)

The shock of rejection turning to rage. This Lear’s anger and madness is more vehement and gestural than that of Raja Lear’s, but not so physicalised as in Iruthiattam. less

Premonition of madness

Lear: O Fool, I shall go mad! [Exeunt Lear, Gloucester, Kent, and Fool.] (II.iv.289) “You unnatural hags,” he vows revenge. But his age cannot withstand such turmoil: “O fool I...more

Lear: O Fool, I shall go mad!

[Exeunt Lear, Gloucester, Kent, and Fool.] (II.iv.289)

“You unnatural hags,” he vows revenge. But his age cannot withstand such turmoil: “O fool I shall go mad.” The storm breaking out was real, with the crashing of clouds and rolling of thunder. In a storm of anger, Lear rushes out with the Fool and his followers. The end business showed the other characters somewhat stunned, they were not expecting this. But they do not make a move. Gloucester is the only one to look around; he hesitates and then shuffles after Lear. While the production played up Lear’s egotism and unreasonableness, it did not spare exposing the others too. less

Goneril’s impatience

Gon: Put on what weary negligence you please, You and your fellows; I’ll have it come to question: If he dislike it, let him to our sister, Whose mind and...more

Gon: Put on what weary negligence you please,

You and your fellows; I’ll have it come to question:

If he dislike it, let him to our sister,

Whose mind and mine, I know, in that are one,

Not to be over-ruled. Idle old man,

That still would manage those authorities

That he hath given away! Now, by my life,

Old fools are babes again; and must be used

With checks as flatteries, when they are seen abus’d.

Remember what I tell you.

Osw: Well, Madam.

Gon: And let his knights have colder looks among you;

What grows of it, no matter; advise your fellows so:

I would breed from hence occasions, and shall,

That I ma speak: I’ll write straight to my sister,

To hold my very course. Prepare for dinner. Exeunt (1.iii.13 – 27)

Goneril’s increasing impatience with Lear’s behaviour; and Oswald, an innovative characterisation of this production. Usually treated as a colorless factotum, here he was given a distinct character and played as a comic type of the over weaning, but shallow, young man on the make who will do anything to please his master or mistress. less

Lear’s ritual preparation for a meal

Horns within. Enter King Lear, Knights, and Attendants Lear: Let me not stay a jot for dinner; go get it ready. Exit an Attendant How now! what art thou? Kent:...more

Horns within. Enter King Lear, Knights, and Attendants

Lear: Let me not stay a jot for dinner; go get it ready.

Exit an Attendant

How now! what art thou?

Kent: A man, sir.

Lear: What dost thou profess? what wouldst thou with us?

Kent: I do profess to be no less than I seem;

to serve him truly that will put me in trust: to

love him that is honest; to converse with him

that is wise, and says little; to fear

judgment; to fight when I cannot choose; and to eat no fish.

Lear: What art thou?

Kent: A very honest-hearted fellow, and as poor as the king.

Lear: If thou be as poor for a subject as he

is for king, thou art poor enough. What wouldst thou?

Kent: Service.

Lear: Who wouldst thou serve?

Kent: You.

Lear: Dost thou know me, fellow?

Kent: No, sir; but you have that in your

countenance which I would fain call master.

Lear: What’s that?

Kent: Authority.

Lear: What services canst thou do?

Kent: I can keep honest counsel, ride, run,

mar a curious tale in telling it, and deliver a

plain message bluntly; that which ordinary

men are fit for, I am qualified in; and the

best of me is diligence.

Lear: How old art thou?

Kent: Not so young, sir, to love a woman

for singing, nor so old to dote on her for any

thing: I have years on my back forty-eight.

Lear: Follow me; thou shalt serve me: if I

like thee no worse after dinner, I will not part

from thee yet. Dinner, ho, dinner! Where’s my

knave? my Fool? Go you, and call my fool

hither. Exit an Attendant (1.iv.8 – 46)

Lear enters after a hunt. An elaborate sequence of stage business deriving from the mimetic traditions of Indian theatre shows the king being helped to undress and wash in preparation for his meal. The hand held curtain of the Indian stage doubles up as a screen, while an ethnic Rajasthani washtub and some jars provide the material and visual signs of the localization. The banished Kent, now in disguise, introduces himself and offers his services to Lear during the process of his toilette. The ritualistic dimension of the scene, enhanced by the live “folksy music” (use of the flute), underlies how the ceremoniousness and authority associated with the monarch had not abated, despite his having given up his kingdom. The courtiers laugh in unison when Lear cracks a joke against Kent, for instance. Note the open stage, with no flats or wings, in simulation of the stafes of Indian folk theatres. less

Oswald’s “slack”

Enter Oswald Lear: You, you, sirrah, where’s my daughter? Osw: So please you, — Exit Lear: What says the fellow there? Call the clotpoll back. Exit a Knight (1.iv.47 –...more

Enter Oswald

Lear: You, you, sirrah, where’s my daughter?

Osw: So please you, — Exit

Lear: What says the fellow there? Call the clotpoll back.

Exit a Knight (1.iv.47 – 50)

Oswald’s cheekiness seems inherent in him and his cocky walk! Here he is the obsequious fool. less

The Fool caps Kent

Enter Fool Fool: Let me hire him too: here’s my coxcomb [Offers Kent his cap Lear: How now, my pretty knave! how dost thou? Fool: Sirrah, you were best take...more

Enter Fool

Fool: Let me hire him too: here’s my coxcomb

[Offers Kent his cap

Lear: How now, my pretty knave! how dost thou?

Fool: Sirrah, you were best take my coxcomb.

Kent: Why, fool?

Fool: Why, for taking one’s part that’s out

of favour: Nay, an thou canst not smile

as the wind sits, thou’lt catch cold

shortly: there, take my coxcomb:

why, this fellow has banished two on’s

daughters, and did the third a

blessing against his will; if thou follow

him, thou must needs wear my

coxcomb. How now, Nuncle! Would I

had two coxcombs and two daughters!

Lear: Why, my boy?

Fool: If I gave them all my living, I’d keep my

coxcombs myself. There’s mine; beg

another of thy daughters.

Lear: Take head, sirrah; the whip.

Fool: Truth’s a dog must to kennel; (1.iv.100 – 119)

The Fool’s critique: crowning Kent with his cap. “If though folow him thou must needs wear my coxcomb.” The Shakespearean Fool is successfully localised into the genre of the vidushska or fool of Sankrit drama and its folk variants. This Fool is not played as a courtly jester, but as a folksy witty clown, singing and entertaining, signified by his plain outfit and yellow painted face – usualy of street magicians. His playful pungent manner may be placed in the middle of the scale between the somewhat “didactic” wittiness of Raja Lear’s Fool and the openly satirical and acrobatic komali / Fool of Iruthiattam. less

The Fool’s wit in song

Fool: Mark it, Nuncle. Have more than thou showest, Speak less than thou knowest, Lend less than thou owest, Ride more than thou goest, Learn more than thou trowest, Set...more

Fool: Mark it, Nuncle.

Have more than thou showest,

Speak less than thou knowest,

Lend less than thou owest,

Ride more than thou goest,

Learn more than thou trowest,

Set less than thou throwest;

Leave thy drink and thy whore,

And keep in-a-door,

And thou shalt have more

Than two tens to a score.

Kent: This is nothing, Fool.

Fool: Then ’tis like the breath of an unfee’d

lawyer; you gave me nothing for’t. Can

you make no use of nothing, Nuncle?

Lear: Why, no, boy; nothing can be made out

of nothing.

Fool: [to Kent] Prithee, tell him, so much the

rent of his land comes to: he will not

believe a Fool.

Lear: A bitter Fool!

Fool: Dost thou know the difference, my boy,

between a bitter Fool and a sweet one?

Lear: No, lad; teach me.

Fool: That lord that counsel’d thee

To give away thy land,

Come place him here by me,

Do thou for him stand:

The sweet and bitter Fool

Will presently appear;

The one is motley here,

The other found out there.

Lear: Dost thou call me fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away;

that thou wast born with. (1.iv.123 – 155)

Fool’s song in a choric mode with a typical folksy Indian tune and little drum. The knights clap, whistle and dance in a chorus, and Lear enjoys this fun. This is the boisterousness which Goneril calls a riot. less

Goneril and Lear clash

Enter Goneril Lear: How now, daugher! what makes that frontlet on? Methinks you are too much o’ late i’ th’ frown. Fool: Thou wast a pretty fellow when thou hadst...more

Enter Goneril

Lear: How now, daugher! what makes that

frontlet on? Methinks you are too much

o’ late i’ th’ frown.

Fool: Thou wast a pretty fellow when thou

hadst no need to care for her frowning;

now thou art an O without a figure. I am

better than thou art now; I am a Fool,

thou art nothing.

[To Goneril] Yes, forsooth, I will hold my

tongue; So your face bids me, though

you say nothing.

Mum, mum!

He that keeps nor crust nor crum,

Weary of all, shall want some.

[Pointing to Lear] That’s a sheal’d peascod.

Gon: Not only, Sir, this your all-licens’d Fool,

But other of your insolent retinue

Do hourly carp and quarrel, breaking forth

I had thought, by making this well known unto you,

To have found a safe redress; but now grow fearful,

By what yourself too late have spoke and done,

That you protect this course, and put it on

By your allowance; which if you should, the fault

Would not scape censure, nor the redresses sleep,

Which, in the tender of a wholesome weal,

Might in their working do you that offence,

Which else were shame, that then necessity

Will call discreet proceeding. (1.iv.197 – 222)

Goneril and Lear clash. Notice Goneril’s body language: its not so much her brow but her back that is stiff and unbending. She has already acquired an authoritarian edge and lost the sugariness of the first scene. The stage business of serving Lear his meal, a nourishment, is carried on in ironic juxtaposition with the dialogue of discord. less

Cordelia’s truth

Cor: Good my lord, You have begot me, bred me, lov’d me; I Return those duties back as are right fit, Obey you, love you, and most honour you. Why...more

Cor: Good my lord,

You have begot me, bred me, lov’d me; I

Return those duties back as are right fit,

Obey you, love you, and most honour you.

Why have my sisters husbands, if they say

They love you all? Happily, when I shall wed,

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty.

Sure I shall never marry like my sisters,

To love my father all.

Lear: But goes thy heart with this?

Cor: Ay, good my lord.

Lear: So young, and so untender?

Cor: So young, my lord, and true. (1.i.95 – 107)

One she has gathered the strength to speak out her mind, this Cordelia continues, undaunted by the father’s rebuke, with her statement. What is noticeable is the manner in which she pursues the agitated King who moves downstage in anger, circles around him and then follows him across to front stage, explaining her views to convince him of her truth. This Cordelia is not cowed down either by Lear’s authority of the formality of the occasion, she does not flinch to speak directly facing up to the King. Her confidence arises out of the privilege of being the most favoured daughter. The Cordelia of Raja Lear speaks more out of a moral rectitude, discharging a painful duty, while in Iruthiattam, she speaks impelled by a sense of duty towards the people. less

Lear’s curse

Lear: Let it be so; thy truth then be thy dower: For, by the sacred radiance of the sun, The mysteries of Hecate and the night; By all the operation...more

Lear: Let it be so; thy truth then be thy dower:

For, by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night;

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be;

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this for ever. The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbor’d, pitied, and reliev’d,

As thou my sometime daughter. (1.i.108 – 119)

The patriarch-king’s curse: he raises his palm and pronounces doom in the familiar manner of the irascible sages of Indian mythology, whose curses once uttered could not be taken back and whose punishments were always in excess of the transgressions committed. Live music in this production complements and enhances the moods. Here drumbeats are used to emphasize the catastrophic nature of the moment. less

France proposes to Cordelia

France: Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich, being poor; Most choice, forsaken; and move loved, despised! Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon: Be it lawful I take up...more

France: Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich, being poor;

Most choice, forsaken; and move loved, despised!

Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon:

Be it lawful I take up what’s cast away.

Gods, gods! ’tis strange that from their cold’st neglect

My love should kindle to inflamed respect.

Thy dowerless daughter, King, thrown to my chance,

Is Queen of us, of ours, and our fair France:

Not all the dukes of wat’rish Burgundy

Can buy this unpriz’d precious maid of me.

Bid them farewell, Cordelia, though unkind:

Thou losest here, a better where to find. (1.i.250 – 261)

France’s proposal to Cordelia: the dance-like encircling movement, by France around Cordelia is reminiscent of a similar movement of a traditional Indian romantic folk dance, raas. This is to be contrasted with the western gesture of professing love, the kneeling down, as used to Raja Lear. less

Goneril and Regan confer

Gon: Sister, it is not a little I have to say of what most nearly appeartains to us both. I think our father will hence to-night. Reg: That’s most certain,...more

Gon: Sister, it is not a little I have to say of

what most nearly appeartains to us both. I

think our father will hence to-night.

Reg: That’s most certain, and with you;

next month with us.

Gon: You see how full of changes his age

is; the observation we had made of it hath

not been little: he always lov’d our sister

most; and with what poor judgment he hath

now cast her off appears too grossly.

Reg: ‘Tis the infirmity of his age: yet he

hath ever but slenderly known himself.

Gon: The best and soundest of his time

hath been but rash; then must we look from

his age, to receive not alone the

imperfections of long-engraffed condition, but

therewithal the unruly waywardness that

infirm and choleric years bring with them.

Reg: Such unconstant starts are we like

to have from him as this of Kent’s banishment.

Gon: There is further compliment of leave –

taking between France and him. Pray you,

let’s hit together: if our father carry authority

with such dispositions as he bears, this last

surrender of his will but offend us.

Reg: We shall further think of it.

Gon: We must do something, and i’ th’

heat. Exeunt (1.i.283 – 308)

Goneril and Regan expose their true natures in their exchange with each other. While their observations about Lear are acute, they decide to act to consolidate their own newly gained positions, revealing not a jot of concern for the aging father. Note their lust for power, which shows itself in their suggestive body language and arrogant, imperious gestures: swaying hips and swishing skirts, imperious flicks of the head, alternating angry and conspiratorial tones, and the way they chew words and spit out phrases. less

Edmund’s soliloquy

Edm: For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines Lag of a brother? Why bastard? Wherefore base? When my dimensions are as well compact, My mind as generous, and...more

Edm: For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? Wherefore base?

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true,

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With base? with baseness? bastardy? base, base?

Who, in the lusty stealth of nature take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth, within a dull, stale, tired bed,

Go to the creating a whole tribe of fops,

Got ‘tween asleep and wake?

Well, then, Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land: (1.ii.5 – 16)

Edmund’s soliloquy full of, not so much righteous angst and calculated revenge as in Raja Lear, but a natural “low” cunning and villainy. Note his casual manner, normal tone and apparent lack of anger. Edmund in Iruthiattam, is more the type of the renegade son. less

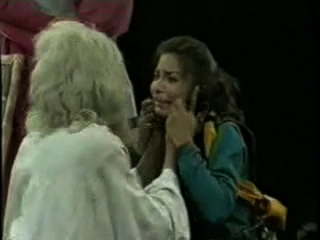

Cordelia’s “nothing”

Lear: Now, our joy, Although our last, and least; to whose young love The vines of France and milk of Burgundy Strive to be interest’d; what can you say to...more

Lear: Now, our joy,

Although our last, and least; to whose young love

The vines of France and milk of Burgundy

Strive to be interest’d; what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters? Speak.

Cor: Nothing, my lord.

Lear: Nothing?

Cor: Nothing.

Lear: Nothing can come of nothing. Speak again.

Cor: Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth: I love your Majesty

Accordingly to my bond; no more nor less. (1.i.82 – 93)

In a marked change of tone and body language, Lear turns with pleasurable expectation towards Cordelia, clearly dearer to him (he had entered the court room together with her, his hand on her shoulder) than the other daughters. Cordelia, too, needs to begin by touching the father-king’s feet, a gesture of respect towards the elder. She looks more obviously troubled than the Cordelia of _Raja Lear_ (while that of _Iruthiattam_ is quite forthright) by what she is being asked to do; she hesitates longer and remains silent until prodded by Lear and then in a constrained manner says “Nothing.” Take aback, this Lear is quite sharp with his rejoinder “Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again!” This Cordelia replies strongly, confidently, compelled out of emotion, walking up to the father who has moved back in agitation, “I love your Majesty according to my bond; no more nor less.” less

Storm scene

Lear: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow! You cataracts and hurricanes, spout Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks! You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires, Vaunt-couriers to...more

Lear: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanes, spout

Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks!

You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head! And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world,

Crack Nature’s moulds, all germens spill at once,

That makes ingrateful man!

Fool: O Nuncle, court holy water in a dry

house is better than this rain water out o’

door. Good Nuncle, in, and ask thy

daughters blessing! Here’s a night pities

neither wise men nor fools. (III.ii.1 – 13)

The storm scene with a heightened realism to make real the storm within Lear. Bathed in a blue night light with a dappled effect of light streaking down from between the clouds and the roll of thunder, the actors were being whipped by the wind and pelted by the rain. The storm was “not synthetic by a cataclysmic crack of doom” (John Russell Brown). In his rage Lear dares the tempest to do its worst: “Blow, winds … Crack Nature’s moulds…” The impact of the realistic staging of this scene, however, is to pit Lear’s rage against nature’s, dwarfing it at times. In _Raja Lear_, the minimal / symbolic sound and light effects let Lear dominate the scene, while in _Iruthiattam_, the stylised staging magnifies the storm, universalizing it. less

Lear’s speech to his daughters

Lear: Tell me, my daughters, Since now we will divest us both of rule, Interest of territory, cares of state), Which of you shall we say doth love us most?...more

Lear: Tell me, my daughters,

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state),

Which of you shall we say doth love us most?

That we out largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge. Goneril,

Our eldest-born, speak first. (1.i.48 – 54)

Lear’s first speech announcing the love-test is a rhetorical public statement spoken out to the audience with very brief glances at his audience, which is standing alongside, but a little behind. There is little eye contact with his listeners, signifying his egotism. less

Goneril’s ritualistic flattery

Gon: Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter; Dearer than eye-sight, space, and liberty; Beyond what can valued, rich or rare; No less than life, with...more

Gon: Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter;

Dearer than eye-sight, space, and liberty;

Beyond what can valued, rich or rare;

No less than life, with grave, health, beauty, honour;

As much as child e’er lov’d, or father found;

A love that makes breath poor and speech unable;

Beyond all manner of so much I love you.

Cor: [Aside] What shall Cordelia speak?

Love, and be silent.

Lear: Of all these bounds, even from this line to this,

With shadowy forests and with champains rich’d,

With plenteous rivers and wide-skirted meads,

We make thee lady: to thine and Albany’s issue

Be this perpetual. What says our second daughter,

Our dearest Regan, wife to Cornwall? (1.i.55 – 68)

The two elder daughters reciprocate with conventional formal ceremoniousness: Goneril touches the father-king’s feet in the prescribed traditional manner and professes her love with a studied sugariness. Lear is pleased but does not look at Goneril while she tries to flatter him. Instead, he looks straight out, very much the monarch used to receiving tributes, lapping up the ceremonial without a flicker of emotion. When he turns to Goneril, however, he is pleased that she has observed form and he gives her her just reward. Cordelia’s reservations about this love and property barter are voiced. less

Opening sequence: the grand entry

Sennet. Enter one bearing a coronet, King Lear, Cornwall, Albany, Goneril, Regan, Cordelia, and Attendants. This production opens with Gloucester and Kent in conversation followed by the entry, with fanfare,...more

Sennet. Enter one bearing a coronet, King Lear, Cornwall, Albany, Goneril, Regan, Cordelia, and Attendants.

This production opens with Gloucester and Kent in conversation followed by the entry, with fanfare, of Goneril, Regan and their husbands who come in and take their places. Lear enters heralded by a more elaborate, but slow and ponderous, fanfare taking his time to walk downstage, his arm resting on Cordelia’s shoulder who accompanies him – the necessary build up for a scene in which the ceremonies ritualistic dimension is emphasized. The backdrop, a set of tall columns and a central medallion emblazoning a court, sets off Lear’s authoritarianism. The localization into a royalist Indian scene is swiftly worked in not just by the costumes, headgear (North Indian and traditional) and the music, but also by the formality of an obviously public occasion – a red carpet was rolled out.

Familial relations in India are traditionally expressed in formal and ritualistic terms. Three of the older characters, Lear, Gloucester and Kent are given whitened, mask-like to emphasize their generational distance from the rest of the younger characters. The generational conflict is a particular focus of this production.

The manner of the opening sequence, of how Lear, particularly, is introduced to the audience becomes a key to the mood and interpretation of the whole production. Samrat Lear clearly presents the King as a typical authoritarian ruler, very much in control, commanding rotal attention. This is a sharp contrast to the introduction of Raja Lear in which the King is more of a self-absorbed patriarch figure and Iruthiattam in which he is satirized as a whimsical and uncontrollable old man.

Note the open stage, with no wings, flies and lowered lights, which is a conscious attempt at a demystification and decanonisation of the realistic tradition of staging Shakespeare. Inspired by the conventions of Indian folk theater, the open stage is part of the localizing impetus: “to give a fee of the open acting spaced of the jatra or kudiattam” (John Russell Brown). The “opened up” stage also functions as an opening up of the play facilitating the performance of the play more like a saga or narrative, than like a personal tragedy, another convention of the Indian folk theatres. less

Artful Regan

Reg: I am made of the self metal as my sister, And prize me at her worth. In my true heart I find she names my very deed of love;...more

Reg: I am made of the self metal as my sister,

And prize me at her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love;

Only she comes too short: that I profess

Myself an enemy to all other joys

Which the most precious square of sense possesses,

And find I am alone felicitate

In your dear Highness’ love. (1.i.69 – 76)

Regan is showier, touching the father-king’s feet in a more ceremonious manner. She speaks alternating between imperiousness and artfulness, playing to the occasion, relishing the public attention, and again Lear looks away, impassive, as if he was listening to what he expected. He acts more the monarch than the father. less

Essays

Shakespeare in India: Modes of Performance

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional.more

- Universalized Shakespeare

- Localized Shakespeare

- Indigenised Shakespeare

- English Language Shakespeare

The universalized Shakespeare stream is seen through a Marathi production, directed by Sharad Bhuthadia, by profession a pediatrician, but belonging to a category prominent in India, of the amateur professional. These are artists who do not earn their main living in theatre, yet devote all their leisure and creative energy to it, run theatre groups and even travel with their shows to different parts of the country. Bhuthadia’s group, Pratyaya, chose to perform Lear inspired by the much acclaimed translation by Vinda Karnadikar, eminent Marathi poet, who is able to capture the nuances of Shakespeare’s language without sacrificing its images or allusions.

A faithful translation, it was performed in a manner ‘faithful’ to the tradition of realist staging of Shakespeare. This has been the most common staging practice for Shakespeare in India. Based on universalist assumptions of a stable and authoritative text, it performs Shakespeare straight letting the text speak for itself. It seeks to let the past live in the present, playing up its foreignness. Though sometimes critiqued as “derivative” and “essentialising,” this universalist staging practice, particularly in our colonial and postcolonial context, functions as an empowering mimicry. “Doing it like them” becomes a mastering of the master colonising text.

Further, the group, Pratyaya, coming from a provincial town like Kolhapur, is able to eschew the market rules of Bombay theatre: “Ours is a focused outlook on theatre,” says Sharad Bhuthadia, asserting that they choose to do meaningful theatre which can “go beyond and handle genuine human problems by going deep into the understanding of man’s life” (quoted in a review, Independent Journal of Politics and Business, 20 August 1993). Bhuthadia’s Raja Lear thus did not need any further entry points into the play, and while it performed an edited version, in three acts, it nevertheless, did full justice to the main themes of the play.

Its singular achievement was a deeply felt and internalized performance, not always easy for Shakespeare in translation; it received universal praise: “A high-powered fidelity to a Shakespearean text…. Never before had Marathi sounded so good on stage. Raja Lear was not just believable, it was real,” said R Ramanathan in the Independent Journal, while the Indian Express (20 August 1993) titled it a “Class Act.”

So successful was the universalizing of this production that critics had no difficulty in contemporising the play: “Lear becomes the tragedy of the India we are living in – the tragedy of a great nation being torn apart by centrifugal forces: of a political class composed of an imbecile king surrounded by sycophants (Regan and Goneril) and ruthless manipulators (Edmund); of the voices of sanity being disowned (Cordelia) and banished (Kent) or simply disappearing (Fool); of goodness having to pretend insanity (Edgar). Lear, then, does not remain the tragedy of one man. It becomes the tragedy of an entire people, an epoch.” (Sudhanva Deshpande, The Times of India, January 1993).

The localized Shakespeare is another performative style, particularly favoured in the earlier years, which imported a definite Indian flavour and colouring to transform the alien vastness of the text into an accessible familiarity. The degree of change varied: while the adaptations of the Parsi theatre in the 1880s took great liberties with Shakespeare’s plot, character and even words, the post- independence localizations have been attempts to root Shakespeare more acutely in a specific local ambience. The production, chosen to illustrate this stream of performance, is a student production of the National School of Drama. Samrat Lear, directed by John Russell Brown.

The National School of Drama, in New Delhi, has a tradition of inviting directors from different parts of the country and from abroad to train their students in a variety of performative styles. Visiting English directors have often chosen to direct Shakespeare even though the performances are always in a Hindi translation. John Russell Brown’s production played almost the full text – a marathon three and half hour long performance – in a translation by Harivansh Rai Bachchan, one of the foremost Hindi poets of the twentieth century. Brown’s own closeness and expertise with the English text gave the production sharply etched characterisation, robust energy, and a particular focus on the narrativisation of the story.

Its localization was not to resituate the story in another well-defined place or period, but to let its relocation emerge from the theatrical event in Delhi. “I have not localised the story in any specific way,” Brown said in an interview with the author, “because we were not doing an “authentic” Indian production. I wanted this Lear to speak beyond the moment.” To this end, he said, he had “encouraged the [student] actors to use their own ‘folk’ physicalities, (their own understandings of their theatre traditions) in their responses to s,” because he believed that a “play lives between the actor and the audience.” The result was a fairly successful attempt to meld the conventions of the traditional theatre, the style of the modern Indian theatre with the speech rhythms of Hindi onto the story of Shakespeare.

Traditional Indian costuming and music added the finishing touches. As Kavita Nagpal, seasoned theatre critic, remarked, the production made “the play breathe in a way that was both historical and contemporary” (Hindustan Times, 15 March 1997). Both these productions, the universalized Shakespeare, Raja Lear, and the localized Shakespeare, Samrat Lear, though divergent in their performative styles, shared a conventional interpretative stance. They ventured no innovative critical perspectives on the text, trusting a ‘straight’ telling of the tale. They both proved that Shakespeare in translation could successfully speak to its audiences.

The indigenised Shakespeare is perhaps the most creative and, therefore, somewhat controversial form of staging Shakespeare in India. Here, the Shakespeare text is not just adapted but appropriated and acculturated into an indigenous theatre form. Devotees of the literary text find this kind of transformation a desecration; yet successful indigenisations, which immerse Shakespeare’s text into another aesthetic and cultural worldview, can spark off new meanings and fresh configurations of the same text. The production chosen to illustrate this genre of performance is a rewritten version of Lear entitled Iruthiattam (The Final Game) directed by R. Raju from a Tamil translation and adaptation made by well-known novelist and playwright, Indira Parthasarathy and presented by the theatre group, Arangam. R. Raju, from the School of Performing Arts at Pondicherry University, and a former NSD graduate, belongs to the Kerala school of experimental theatre, the ‘nataka karali,’ making appropriation and adaptation his metier. And Arangam is no ordinary theatre group either; it consists of highly skilled artists – dancers, musicians and folk theater practitioners – in their own right. Together they created a tightly structured, economical production distinguished by consistency and unity of rasa or mood. It interprets the play in terms of a power struggle, retains part of the sub-plot to make a feminist point that sons too can be cruel, and ends with the storm scene at the end of which Cordelia appears to rescue Lear.

But its indigenisation derives more from its performative style, which adapts the conventions of the terukutoo, a popular street theatre folk form of Tamil Nadu, traditionally performed by the socially disadvantaged. The inherent subversivness and spontaneity of the terukutoo, centering on the improvisatory energy of the fool I komali, was the main interpolation into the text and this was specially manifested in the highlighting of a contrapuntal relationship between the fool and the king. The strong phyicalised style, acrobatic and earthy, with its vigorous song and dance routines, made Iruthiattam lively and entertaining, transforming King Lear from a reworked classic into a kind of a ‘people’s Shakespeare.’

Even though the adaptation was titled “The Final Game” it did not in the least subscribe to a Beckett-like doom and gloom of Endgame. Since this version took liberties to play around with and cut up Shakespeare’s canonical text to suit its own radicalising perspective, it may also be seen as an example of the postcolonial Shakespeare.

Apart from these, the English language Shakespeare is best represented by an amateur student production of King Lear by the St. Stephen’s College Shakespeare Society, one of the oldest collegiate dramatic societies with an almost unbroken record of performing Shakespeare for over 75 years since 1924. Arjun Raina, a young actor director worked closely with the students drawing out their impressions and structuring them into stageble ideas. The production was marked by an iconoclastic irreverence, at times a plainly undergraduate-ish swipe at tradition, which nevertheless produced some novel stage images, e.g. the introduction of a whimsical Lear in boxer shorts and gloves brought onstage reclining in a brightly coloured coffin symbolizing the death of the monarch.

The rest of the cast sat on and moved around with high but crude wooden stools that wobbled and wavered at every step, imaging Lear’s world as full of social climbers caught in the instabilities of the social hierarchy. The characteristic opening sequence had all the court, clad in black and white, looking harlequinesque, streaming in to ‘view’ the show of Lear’s division of the spoils through tinseled masks and opera glasses (these were changed to dark glasses after the blinding of Gloucester) as also looking, observing, spying on each other – all heightened, perched on the wooden stools. Lear chased his screaming daughters down the stage and then pieces of cake were passed around during the division of the kingdom.