Excerpted from “Shakespeare and Translation.” The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts, ed. Mark Thornton Burnett, Adrian Streete, and Ramona Wray. Edinburgh University Press, 2011. pp. 68-87.

Full text available at: gwu.academia.edu/joubin

Catherine: I cannot tell vat is dat.

King Harry: … I will tell thee in French … Je quand sur le possession de France, et quand vous avez le possession de moi,–let me see, what then? … It is as easy for me, Kate, to conquer the kingdom as to speak so much more French. …

Catharine: Sauf votre honneur, le Francois que vous parlez, il

est meilleur que l’Anglois lequel je parle.King Harry: No, faith, is’t not, Kate: but thy speaking of my

tongue, and I thine, most truly-falsely, must needs be granted to be much at one. But, Kate, dost thou understand thus much English, canst thou love me?—Henry V 5.2.169-183

Literary translation is a love affair. Depending on the context, it could be love at first sight or hot pursuits of a lover’s elusive nodding approval. In other instances it could be unrequited love, and still others a test of devotion and faith. Or an eclectic combination of any of these events. Translation involves artistic creativity, not a workshop of equivalences. As human civilisations developed and intersected, translation emerged as a necessary form of communication and a way of life. It highlighted and put to productive use the space between cultures, between individuals with different perspectives, and within one’s psyche.

To think of translation as a love affair does not eliminate the hierarchies that are part of the historical reality. In terms of its symbolic and cultural capital, literary translations always reflect the global order of the centre and the peripheral. Shakespeare remains the most canonical of canonical authors in a language that is now the global lingua franca. Translating Shakespeare into Zulu produces very different cultural prestige than translating Korean playwright Yi Kangbaek into English. Does translating Shakespeare empower those for whom English is a second language, or reinforce cultural hegemony? There is no simple answer. When his translation of Hamlet was published, King D. Luis was praised in 1877 for bringing honour to his country by “giving to the Portuguese Nation their first translation of Shakespeare” (Pestana, 1930, 248-263). In contrast, the Merchant-Ivory’s metatheatrical film Shakespeare Wallah interrogates this sense of entitlement and prestige. Following the footstep of the English director Geoffrey Kendal’s travelling company in India, we see the country’s ambiguous attitude towards Shakespeare and England. Translations, as they age, also serve as useful historical documents of past exigencies and cultural conditions (Hoenselaars, 2009, 278-279). In what follows, we shall consider literary translations in their own right and in relation to one another and other texts.

Shakespeare in Borrowed Robes

One of the most thought-provoking cases of literary translation is Shakespeare, the most widely translated secular author in the past centuries, with several editions in many languages (e.g., the Complete Works has been translated into German a number of times beginning with the German Romantics, and into Brazilian Portuguese by Carlos Alberto Nunes in 1955-67 and by Carloes de Almeida Cunha Medeiros and Oscar Mendes in 1969). Literary translation sometimes modernises the source text (Eco, 2001, 22), which brings the text forcefully into the cultural register of a different era. As such, Shakespeare in translation acquired the capacity to appear as the contemporary (and ideal companion) of the German Romantics, a spokesperson for the proletarian heroes, required reading for the Communists, and even a transhistorical icon of modernity in East Asia. Even new titles given to Shakespeare’s plays are suggestive of the preoccupation of the society that produced them, such as the 1710 German adaptation of Hamlet title Der besträfte Brudermord (The Condemned Fratricide) and Sulayman Al-Bassam’s The Al-Hamlet Summit (English version in 2002; Arabic version in 2004). While Western directors, translators, and critics of The Merchant of Venice tend to focus on the ethics of conversion and religious tensions with Shylock at center stage, the play has a completely different face in East Asia with Portia as its central character and the women’s emancipation movement in the nascent capitalist societies as its main concern, as evidenced by its common Chinese title A Pound of Flesh, a 1885 Japanese adaptation of The Merchant of Venice titled The Season of Cherry Blossoms, the World of Money, and a 1927 Chinese silent film The Woman Lawyer.

Shakespeare’s oeuvre is present on every populated continent, with sign-language renditions and recitations in Klingon in the Star Trek to boot. Hamlet is one of the most frequently translated and staged plays in the Arab world (Mohamed Sobhi’s 1977 version in Egypt, Khaled Al-Tarifi’s version in Jordan, and more). Since its first staging in Copenhagen in the early nineteenth century, Hamlet has both visceral and historical connections with Denmark (Hansen, 2008, 153)—thanks in part to the famed “Hamlet castle” Kronborg. King Lear has a special place in Asian theatre history and Asian interpretations of filial piety. Romeo and Juliet enjoys a global renaissance in genres ranging from punk parody to Japanese manga. The Sonnets and The Merchant of Venice have been translated into te reo Maori of New Zealand and hailed as a major cultural event. By 1934, Shakespeare had been translated into over 200 Indian languages using Indian names and settings. Shakespeare has come to be known as unser Shakespeare for the Germans, Sulapani in Telegu, and Shashibiya in Chinese.

This is not to say that translating Shakespeare is always a rosy undertaking, or that Shakespeare has a universal appeal. Wars, censorship, and political ideologies can suppress or encourage the translation of particular plays or genres for one reason or another, or outlaw Shakespeare altogether (as is the case during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976). The 1930s is a time when the political expediency drove readers, performers, and audiences to a select set of Shakespearean plays in the Soviet Union, Japan, and China. The regicide and assassinations in Hamlet raised the eyebrows of the Japanese censors in the decade when Japan was preparing to challenge European and American supremacy. Hamlet was banned, along with half a dozen other left-wing plays, at the International Theatre Day organized by the Japan League of Proletarian Theatres (led by Murayama Tomoyoshi) on February 13, 1932, on the ground that the play may motivate rebellions against the rightist government. Ironically, Stalin expressed distaste for dark, tragic plays such as Hamlet, having famously declared that life has become more joyful for the communist state in 1935. Shakespeare’s comedies fit the propagandistic goal and therefore had a firm place in the state-endorsed repertoire for the stage and reading materials in the USSR and its close ally, China, of the time. Shakespeare became, in the Soviet and Chinese ideological interpretations, the spokesperson for the proletariat, an optimist, and a fighter against feudalism, through the “bright” comedies such as Much Ado About Nothing.

Genres and Translation

Genres have a role to play in translation as well. The tragedies and some comedies are more frequently translated, staged, and filmed around the world, because of their capacity to be more easily detached from their native cultural settings and the self-reinforcing cycle of familiarity. In India, for example, Hamlet and the Merchant of Venice have been translated more than fifty times and The Comedy of Errors has over thirty versions in different languages in India, but the only history plays to have been translated into Hindi are Henry V and Richard II, and only one version each. While Shakespeare’s global reputation may seem to be driven by translations of his tragedies, comedies, and the sonnets because of the sheer number of performances and translations since the seventeenth century, the history plays have their own histories of global reception beginning with a 1591 Polish performance of Philip Waimer’s stage version of Edward III in Gdansk. Laurence Olivier’s wartime film version of Henry V in 1944 is far from the only or the earliest translations—interlingual, intralingual, or intersemiotic—of the history plays, though each instance of translation focuses on different articulations of national histories.

British performances, understandably, are more frequently geared toward constructing a coherent national identity in relation to Britain’s friends and foes on the European continent (Hoenselaars, 2004, 9-34). Non-anglophone translations of history plays, on the other hand, often use the plays to interrogate the notion of national history. One of the better-known examples in the West is Richard III: An Arab Tragedy by Sulayman Al-Bassam of Kuwait, a production that has toured widely around the world. Plays such as Henry V that polarizes the English and the French have a contentious reception in France and Europe, serving as a forum for artistic experiment and political debates. Still farther ashore, plays from both the first and second tetralogies, excluding King John, found new homes in nationalist projects of modernization and school performances in Japan, Taiwan, China, and elsewhere. While the Asian translators and adaptors’ interest did not always lie in medieval English history (or Shakespeare’s imagination thereof), such as the feud between the Houses of York and Lancaster, they drew parallels to inspire analogous reflections on local histories. Kinoshita Junji’s translations of Henry VI and Richard III echoes The Tale of the Heike, a thirteenth-century Japanese literary masterpiece chronicling the clashes between the Heike and the Genji clans. Henry IV appeared in prose as a serialised story in The Short Story Magazine in early twentieth-century Shanghai. It was soon published as a volume and prominently advertised. Its appeal was due in no small part to the Chinese discourse of modernity and unified national identity in a time of national crisis as the country was threatened by Japanese and European colonial powers. The Chinese intellectuals of the time looked outward for other nations’ experiences. More recently, Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 were adapted into a play for the Taiwanese glove puppet theatre in 2002, a hybrid genre blending elements of Chinese opera, marionette theatre, and street theatre.

By the twenty-first century, all of Shakespeare’s plays, followed by the Sonnets, have had long histories of translation. 2009 witnessed the publication of a 748-page critical anthology with a title that parallels and talks back to the 69-page quarto of 1609: William Shakespeare’s Sonnets for the First Time Globally Reprinted: A Quartercentenary Anthology with a DVD, containing samples of the sonnets translated, performed, or parodied in more than 70 languages and dialects. Since Shakespeare’s sonnets in translation have been discussed extensively in the anthology, this chapter will focus on the plays. The spread of Shakespeare’s work has accelerated due to the rapid localisation of globally circulating ideas and with the globalisation of local forms of expression, fuelled first by trade and slavery, and now by the digital and Internet culture. A new age of Shakespeare in translation is upon us.

Translators and Adapters

Many of the translators of Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets are major figures in the world of letters in and beyond their own cultures: August Wilhelm von Schlegel and Paul Celan in Germany, Boris Pasternak in Russia, Tsubouchi Shōyō in Japan, Liang Shiqiu in Taiwan, Julius K. Nyere in Tanzania, Aimé Césaire in Martinique, Rabindranath Tagore in India, Voltaire in France, Elyas Abu Shabakeh in Syria, Wole Soyinka in Nigeria, Charles and Mary Lamb in England, and countless others. Some cultures have canonical, received versions for readers and actors, such as Zhu Shenghao’s Chinese translation of The Complete Works, but the audience in other cultures, notably France, cannot claim to have any set of standard translations (Morse 2006, 79). There are numerous stage and film directors, painters, composers, choreographers, and artists, who engage and transform Shakespeare, as discussed in other chapters in this volume. The proliferation of Shakespeare in translation, especially in non-European languages, makes nonsense the notion of a homogenized, authenticated Shakespeare in British English.

Translation is far from a one-way street from the English text to a foreign one. Rewritings of Shakespeare sometimes refer to and borrow from one another, resembling the process of cross-pollination. Examples include Chee Kong Cheah’s Chicken Rice War, a Singapore film that parodies Baz Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, and Wu Hsing-kuo’s reading of Macbeth in his The Kingdom of Desire, a Beijing opera play, that alludes to Akira Kurosawa’s film Throne of Blood. These borrowings have enriched our understanding of Shakespeare and world cultures. It is noteworthy that Shakespeare was not always translated directly from English into foreign languages. Because of historical or political reasons, double or triple filtering was not uncommon. When composing the choral symphony Roméo et Juliette, Hector Berlioz worked from Pierre Le Tourneur’s French translation of David Garrick’s English adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. French neoclassical versions were the foundation for early Russian translations of Shakespeare, while the first Shakespearean performance in colonial Korea was a Japanese version of Hamlet in 1909. Teodoro de la Calle’s 1802 Spanish translation of Othello was based on Ducis’s French version. As a result, Shakespeare in translation has been used as the proving ground of translation theory, and it is the core of the Shakespeare industry.

Translation as a Theme in Shakespeare’s Plays

What country, friends, is this?

Twelfth Night 1.2.1

However, estrangement and transnational cultural flows are not exclusively a modern affair. Cultural exchange was an unalienable part of the cultural life in Renaissance England. Translation, or translatio, signifying “the figure of transport” (Parker 1987, 36-45), was a common rhetorical trope that referred to the conveyance of ideas from one geo-cultural location to another, from one historical period to another, and from one artistic form to another. London witnessed a steady stream of merchants and foreign emissaries from Europe, the Barbary coast, and the Mediterranean, and thousands of Dutch and Flemish Protestants fled to Kent in the late 1560s due to the Spanish persecution. In 1573, Queen Elizabeth I granted Canterbury to have French taught in school to “those who desire to learn the French tongue” (Cross, 1898, 15). The drama of the time reflected this interest in other cultures. Only one of Christopher Marlowe’s plays, Edward II, is set in England, and he translated Book 1 of Lucan’s Civil Wars, an epic canvassing the geographical imaginaries from Europe to Egypt and Africa. Thomas Heywood’s The Fair Maid of the West explores the role of woman and cross-cultural issues. Most of Shakespeare’s plays are set outside England, in the Mediterranean, France, Vienna, Venice, and elsewhere. Even the history plays that focus intently on the question of English identity and lineage feature foreign characters who play key roles, such as Katherine of Aragon in Henry VIII, and the diplomatic relations between England and France. Thomas Kyd flirted with the idea of multilingual theatre in The Spanish Tragedy through a short play-within-a-play scene, “Soliman and Perseda,” in “sundry languages” (4.4.74). Pidgin English is masqueraded as fake Dutch in Thomas Middleton’s No Wit, No Help Like a Woman’s. Other examples abound.

Within Shakespeare’s plays, the figure of translation looms large. Translational moments create comic relief and heighten the awareness that communication is not a given. Translation also served as a metaphor for physical transformation or transportation. Claudius speaks of Hamlet’s “transformation” (2.2.5) and asks Gertrude to “translate” Hamlet’s behaviours in the previous scene (the closet scene) so that Claudius can “understand … the profound heaves” (4.1.2). Gertrude not only relays what Hamlet has just done but also provides her interpretations, as a translator would, of her son’s deeds. More so than Hamlet, Henry V contains several instances of literal translation, including the well-known wooing scene quoted above. Translation serves as a figure of transport, theft, transfer of property, and change across linguistic and national boundaries, as the characters and audience are ferried back and forth across the Channel. The peace negotiations dictate that the English monarch marries the daughter of Charles VI of France, uniting the two kingdoms. The “broken English” (5.2.228) in the light-hearted scene symbolises Henry V’s dominance over Catherine and France after the English victory at the Battle of Agincourt. However, the Epilogue reminds us that the marriage is far from a closure (Epilogue 12), for it produces a son who is “half-French, half-English” (5.2.208). The English conqueror pretends to be a wooer to Catherine of France who cannot reject him freely. One is unsure whether Catherine is speaking the truth that she does not understand English well enough (“I cannot tell”) or just being coy—playing Harry’s game, though Catherine eventually yields to Henry V’s request: “Dat is as it shall please de roi mon père” (5.2.229). Likewise, The Merry Wives of Windsor is saturated by translational scenes. Mistress Quickly receives a language lesson in Latin (4.1), and the French Doctor Caius makes “fritters of English (5.5.143). Shakespeare takes great delight in wordplay, and many comic puns rely on orthographic contrasts and resemblances of pronunciations of words in different languages and dialects. Love’s Labour’s Lost, a polyglot “feast of languages” (5.1.37), features a critique of Armado’s Spanish-inflected orthography by Holofernes (5.1.16-25).

The idea of translation is given a spin in A Midsummer Night’s Dream where the verb to translate is expansive and elastic, signifying transformations most wondrous and strange. Upon seeing Bottom turned into an ass-headed figure, Peter Quince cries in horror: “Bless thee, Bottom, bless thee. Thou art translated!” (3.1.105). Other characters use the verb in similar ways to refer to a broad range of transformations. Helena desires to be “translated” into Hermia (1.1.191), and a love potion transforms characters that come across its path. Indeed stage performances subject actors to various forms of “translation.” In the case of the first performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in London, the stage transforms a Chamberlain’s Men actor to the character of an Athenian weaver named Nick Bottom to the role of a tragic lover, Pyramus, in a play-within-a-play, and to an ass-headed monster—an object of obsession in Titania’s fairy kingdom.

Language barriers emerge as a moment of self-reflection for Portia in The Merchant of Venice even as she uses it to typecast some of her suitors from all over the world. In the first exchange between Narissa and Portia, when asked of her opinion of “Falconbridge, the young baron of England,” Portia goes right to the heart of the problem. Since Falconbridge “hath neither Latin, French, nor Italian,” it is impossible to “converse with a dumb show.” Portia is aware of her own limitations, too. She admits “I have a poor pennyworth in the English,” which is why she can say nothing to him, “for he understands not [her], nor [she] him.” Falconbridge’s odd expression of cosmopolitanism does not fare any better, as Portia observes snidely: “I think he bought his doublet in Italy, his round hose in France, his bonnet in Germany, and his behaviour everywhere” (1.2.55-64).

As products of an age of exploration, Shakespeare’s plays demonstrate influences from a rich treasure trove of multilingual sources in Latin, Italian, Spanish, and French. Arthur Golding’s 1567 English translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a Roman collection of mythological tales, provided a rich network of allusions for Shakespeare’s comedies (e.g., the story of Diana and Actaeon). In Titus Andronicus, the mutilated Lavinia is able to translate and communicate her thoughts via Ovid even though she is unable to speak or write. While other sources provided stories for Shakespeare to embellish, the Metamorphoses was an important stockpile of allusions for Shakespeare. Thomas North’s 1579 version of Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans is a major source for Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and other Roman plays. Shakespeare rendered North’s prose in verse and made numerous changes. Shakespeare knew Latin and French, and was up to date on the translated literature during his times. He probably read Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi in Italian before penning Othello, and regularly looked beyond English-language sources for inspiration for stories to dramatize. It is by no accident that Shakespeare put Julius Caesar’s famous last words in Latin, as “Et tu, Brute?” (3.1.77) rather than Greek in Plutarch, the play’s source. Perhaps, as Casca complains in another scene, “it was Greek to me” (1.2.278). Shakespeare was a great translator in the sense of transforming multiple sources, and he was a talented synthesiser of different threads of narratives.

The important role of translated literature is indisputable in the development of Shakespeare’s art. Shakespeare became a global author—both in terms of his reading and the impact of his work—long before globalisation was fashionable. In 1586 a group of English actors performed before the Elector of Saxony, marking the beginning of several centuries of intercultural performances of Shakespeare. Romeo and Juliet was staged in Nördlingen in 1604, and Hamlet and Richard II were performed on board an English East India Company ship anchored near Sierra Leone in 1607). Four hundred years on, Shakespeare has come full circle. Given Shakespeare’s talents and interest in translational literature, it is fitting that his works have found new homes in such a wide range of languages and genres.

T.S. Eliot’s quip in The Four Quartets aptly captures the journey that is translation. The end of the intercultural journey will take us to where we started and enable us to know the place for the first time. Both translation as a dramatic motif and drama in translation provide useful contexts for sustained reflections on the “fictions of national coherence” in Shakespeare’s times (Levin and Watkins, 2009, 14) and traits that differentiate and unite different cultures in our times. While we will not be able to delve into these early modern cases within the constraints of the volume, it is useful to bear in mind that there is a long and wide history of Shakespeare in translation and transformation.

Three Modes of Translating Shakespeare

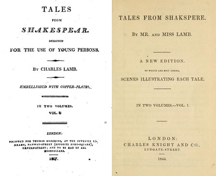

The lack of overt moralisation in Shakespearean dramas, along with other features such as their “vernacular applicability” on screen (Burnett, 2005, 185) and flexibility to accommodate contrasting perspectives through dramatic dialogues, have contributed to their broad appeal around the world—in intralingual rewriting (Charles and Mary Lamb’s nineteenth-century prose narrative, Tales from Shakespeare), interlingual adaptation (Bengali translation of Macbeth), and intersemiotic transformations, to use Roman Jakobson’s theory. The last category encompasses a wide range of transformations of Shakespeare’s work from page to stage, screen, and other media. Adrian Noble’s English production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream “translated” the English text on the page to the language of the stage, while Verdi transformed Othello into Otelo, an Italian opera. John Everett Millais’ painting, “Ophelia” (Tate Britain, London), depicts the tragic death of Ophelia is so memorable that it has become iconic, supplementing, if not replacing, the passages about Ophelia’s demise in Hamlet in popular imaginations. Shakespearean dramas were in fact important sources for many Victorian painters.

Each of these modes offers unique challenges and rich rewards. According to Jakobson, intralingual translation, or rewording, is “an interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs of the same language” which is akin to process of meaning making.  “An array of linguistic signs is needed to introduce an unfamiliar word,” reasoned Jakobson (139). But intralingual translation does not produce complete equivalences. Rewriting Shakespeare’s plays in nineteenth English prose narratives involves making choices about the characters’ motives, “morals” of the play, and even selecting a set of coherent meanings from a wide range of meanings afforded by puns and wordplay. One of the most widely-read and globally influential intralingual translations is Tales from Shakespeare by Victorian author and critic Charles Lamb and his sister Mary. The 1807 text was designed “for young ladies” because, as the Lambs reasoned, “boys being generally permitted the use of their fathers’ libraries … before their sisters are permitted to look into this manly book” (1963, vi). The moralistic, simplified, prose rendition of select Shakespearean tragedies (by Charles) and comedies (by Mary) was initially intended for women and children who would not otherwise have access to Shakespeare’s plays, but it has remained one of the most popular English-language rewritings to this day (fig. 1). Charles Lamb was a respected essayist and critic in his times, considered by such figures as William Hazlitt to be a sounder authority on poetry than Johnson or Schlegel. The Tales from Shakespeare bears the mark of its times, but the collection of twenty stories was an enduring monument to Shakespeare in translation and Victorian literature. Though the Lambs openly acknowledged that their rewriting was gendered and classed, they retained as much phrases and passages from Shakespeare as possible. We find a Hamlet who is caring and grieving for clearer reasons:

“An array of linguistic signs is needed to introduce an unfamiliar word,” reasoned Jakobson (139). But intralingual translation does not produce complete equivalences. Rewriting Shakespeare’s plays in nineteenth English prose narratives involves making choices about the characters’ motives, “morals” of the play, and even selecting a set of coherent meanings from a wide range of meanings afforded by puns and wordplay. One of the most widely-read and globally influential intralingual translations is Tales from Shakespeare by Victorian author and critic Charles Lamb and his sister Mary. The 1807 text was designed “for young ladies” because, as the Lambs reasoned, “boys being generally permitted the use of their fathers’ libraries … before their sisters are permitted to look into this manly book” (1963, vi). The moralistic, simplified, prose rendition of select Shakespearean tragedies (by Charles) and comedies (by Mary) was initially intended for women and children who would not otherwise have access to Shakespeare’s plays, but it has remained one of the most popular English-language rewritings to this day (fig. 1). Charles Lamb was a respected essayist and critic in his times, considered by such figures as William Hazlitt to be a sounder authority on poetry than Johnson or Schlegel. The Tales from Shakespeare bears the mark of its times, but the collection of twenty stories was an enduring monument to Shakespeare in translation and Victorian literature. Though the Lambs openly acknowledged that their rewriting was gendered and classed, they retained as much phrases and passages from Shakespeare as possible. We find a Hamlet who is caring and grieving for clearer reasons:

The young prince . . . loved and venerated the memory of his dead father almost to idolatry, and being of a nice sense of honour, and a most exquisite practiser of propriety himself, did sorely take to heart this unworthy conduct of his mother Gertrude: insomuch that, between grief for his father’s death and shame for his mother’s marriage, this young prince was overclouded with a deep melancholy, and lost all his mirth and all his good looks (290).

Like Henrietta Maria Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare (1807), Tales tapped into the emerging market of books for middle-class children by censoring the “obscenity” in plays such as Othello and removing anything that may be offensive to the Victorian sensibilities.

Between 1999 and 2007, several new editions of the Tales were brought out in English, Chinese, and other languages. Mary Lamb wrote most of the prose stories (Charles wrote only six). It has inspired similar ventures in England and abroad. Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch published a sequel of sort before the nineteenth century winded down: Historical Tales from Shakespeare (1899). It supplemented the Lambs’ text by covering Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, King John, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI and Richard III, most of which the Lambs omitted. The Lambs’ Tales has exerted a great influence in the early reception of Shakespeare in other countries, especially East Asia. The text was reframed in China for the male elite class that operated according to moralizing principles. In 1904, Wei Yi translated it orally, and his collaborator Lin Shu, a prolific translator who could not read English, rendered it into classical Chinese with embellishment. Between 1877 and 1928, the Tales were translated and printed 97 times in Japan, while over a dozen editions appeared in China between 1903 and 1915. Early Japanese productions were based on the Lambs’ Tales rather than complete translations of the plays themselves. The 1868 kabuki production of Julius Caesar and Inoue Tsutomu’s retelling of The Merchant of Venice in 1883, titled “The Suit for a Pound of Human Flesh,” are two such examples (Quinn, 2011, np).

Translating Shakespeare into a foreign language is a different matter. It involves new semantic, semiotic, and cultural contexts. Jakobson believes that “all cognitive experience and its classification is conveyable in any existing language” (140), but when a grammatical category is absent in the target language, its meaning may be translated “by lexical means” (141). While European translators can draw on the shared Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman traditions, the farther a language is situated from the English culture the more creative strategies of displacement a translator will have to deploy. Translating Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech into Japanese, for example, will require substantial rewriting, because Japanese does not have the verb to be without semantic contexts. Jakobson gives a similar example of translating an Italian rhyming epigram (“Traduttore, traditore”) into English (“the translator is a betrayer”). For the English sentence to make sense, the aphorism will have to be elaborated to specify what message the translator conveys and what values he betrays, but the paronomastic value of the epigram will be lost (143). Working with Japanese, a language more complex than English from a sociolinguistic point of view, a translator would have to wrestle with more than 20 first- and second-person pronouns to maintain the ambiguity and subtlety of gender identities in a play such as Twelfth Night. In addition to making the right choice of employing the familiar or polite style based on the relation between the speaker and the addressee, the male and female speakers of Japanese are each confined to gender-specific personal pronouns at their disposal. Before a translation can be undertaken, decisions will have to be made on the register and gendered expressions to convey Orsino’s comments about love from a male perspective and Viola’s apology for a woman’s love when in disguise as Cesario in Twelfth Night, or the exchange between Rosalind in disguise as Ganymede and Oliver on her “lacking a man’s heart” when she swoons, nearly giving herself away (4.3.164-176). But limitations create new opportunities and bring translation closer to an act of performative interpretation.

Differences in grammatical structure aside, bawdy language and puns also pose a challenge. The exchange between Samson and Gregory in Romeo and Juliet presents an opportunity for innovation and self-censorship:

Samson: I will show myself a tyrant: when I have fought with the men I will be civil with the maids—I will cut off their heads.

Gregory: The heads of the maids?

Samson: Ay, the heads of the maids, or their maidenheads, take it in what sense thou wilt.

Gregory: They must take it in sense that feel it.

Samson: Me they shall feel while I am able to stand, and ’tis known I am a pretty piece of flesh (1.1.18-26).

Christoph Martin Wieland’s 1766 German version excised this scene in its entirety and begins with the encounter between Gregory, Samson, Abraham, and Benvolio and the ensuing fight (1.1.29-). Along similar lines, Goethe’s 1812 adaptation of the play (based on Schlegel’s verse translation) presents a sanitized version, turning Romeo from a volatile youth to a more responsible man. References to the lovers’ bodies are replaced by purified language. Juliet’s comment to her nurse that she will die “maiden-widowèd” because “death, not Romeo, take [her] maidenhead” (3.2.135-137) is rid of the reference to virginity. Goethe’s Juliet says that death, not Romeo, follows her to her bridal bed. Cao Yu (1910-1996), an accomplished modern Chinese playwright, felt equally uncomfortable about the passage but approached the issue differently. Diverting the attention from maidenhead to the action of cutting off the head, Cao used the verb gàn to activate the latent connection between cutting off the maids’ heads and Samson’s later comment about his sexual prowess. Gàn has a very wide range of meanings from innocent daily usage to profanity, including to do, to get rid of, and to copulate. Schlegel translated the passage, but used “Jungfrau” (virgin) and “Jungfräulichkeit” (virginity) to translate the wordplay. In addition to translating the “pretty piece of flesh,” Schlegel has Samson say suggestively that the young women will feel the point of his sword (“die Spitze meines Degens”) until it becomes blunt (“stumpf”), which is not found in Shakespeare’s text. Other twentieth-century Chinese translators have come up with various ways to translate this passage, but they share a common problem with the wordplay, because “head” and “maidenhead” in Chinese do not have orthographic and phonetic connections. Zhu Shenghao used nipple to translate this, as the second character of naitou (nipple) is the same as tou (head). In Fang Chong’s revision to Zhu’s translation, the reference to head is excised. Samson threatens to take the women’s lives and elaborated that he might as well take their virginity which they cherish as much as their lives.

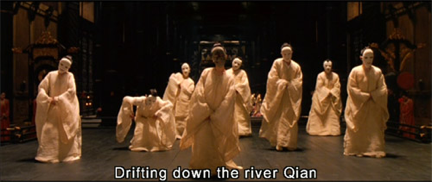

Translating Shakespeare from page to stage or another medium in a different culture involves some of the same challenges outlined above, but it juxtaposes the power of Shakespeare’s words with that of nonverbal expressions and kinetic energy. Intersemiotic translation, or transmutation in Jakobson’s terms, involves the interpretation of “verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (139). It is hardly surprising that it is the intersemiotic transmutations that have buoyed the global Shakespeare industry. Critics are optimistic about Shakespeare without his language and even beyond his genres: “Not needing to record in English on the soundtrack, [filmmakers such as Akira Kurosawa] enjoyed the luxury of reinventing the plays in purely cinematic terms” (Rothwell, 2004, 160). A recent example is a Chinese martial arts film adaptation of Hamlet by Feng Xiaogang (2006), entitled The Banquet and released in North America as the Legend of the Black Scorpion. The film stars Zhang Ziyi, Ge You, Zhou Xun, and Daniel Wu. Set in tenth-century China, the film reimagines the Hamlet narrative through stylised presentation and offers a fresh perspective on traditionally silenced characters such as Ophelia. The English critical and dramaturgical traditions treat Ophelia as a character whose significance lies mostly in information she conveys to the audience on Hamlet. The same is true of Anglophone cinematic representations of Gertrude. Many Western films and productions make Ophelia either childish or irritated, but Feng’s film combines both the qualities of innocence and a passionate lover in its representation of Ophelia. The Banquet gives Qing Nü (fig. 2), the Ophelia figure and a symbol of purity,  palpable and vocal presence in a court inhabited by scheming courtiers, ministers, empress, and usurper. Having gone mad for love of Prince Wu Luan, the Hamlet figure, Qing Nü enters uninvited in the last scene, the coronation of Empress Wan, the Gertrude figure. Seemingly oblivious to her intrusion to one of the most important court ceremonies, she announces that she and a troupe of dancers will perform a love song to honor the late prince who is assumed to be dead. A daring and bold move. The audience is left to ponder whether this act reflects her innocence or calculation, for, in several scenes, Qing Nü has shown her headstrong will to express her love for the prince even at the cost of offending the empress. Qing Nü and her entourage don white, neutral masks reminiscent of those used in noh performances. The song she sings about a boat girl is significant in its reference to Qing Nü’s extra-sensorial communication with the prince: “Trees live on mountains, and branches live on trees / My heart lives for your heart, but you do not see me” (Feng, 2006). Coupled with the masked dance performed by a sane Ophelia figure, Qing Nü’s lyrics echo but also add new meanings to Ophelia’s songs in Hamlet, sung when she is mad: “How should I our true love know / From another one?” (4.5.23-24). The Banquet is an exercise in considering the events from the perspective of Ophelia who takes matter into her own hands (fig. 3 and 4).

palpable and vocal presence in a court inhabited by scheming courtiers, ministers, empress, and usurper. Having gone mad for love of Prince Wu Luan, the Hamlet figure, Qing Nü enters uninvited in the last scene, the coronation of Empress Wan, the Gertrude figure. Seemingly oblivious to her intrusion to one of the most important court ceremonies, she announces that she and a troupe of dancers will perform a love song to honor the late prince who is assumed to be dead. A daring and bold move. The audience is left to ponder whether this act reflects her innocence or calculation, for, in several scenes, Qing Nü has shown her headstrong will to express her love for the prince even at the cost of offending the empress. Qing Nü and her entourage don white, neutral masks reminiscent of those used in noh performances. The song she sings about a boat girl is significant in its reference to Qing Nü’s extra-sensorial communication with the prince: “Trees live on mountains, and branches live on trees / My heart lives for your heart, but you do not see me” (Feng, 2006). Coupled with the masked dance performed by a sane Ophelia figure, Qing Nü’s lyrics echo but also add new meanings to Ophelia’s songs in Hamlet, sung when she is mad: “How should I our true love know / From another one?” (4.5.23-24). The Banquet is an exercise in considering the events from the perspective of Ophelia who takes matter into her own hands (fig. 3 and 4).

The stage also provides infinite possibilities for intersemiotic translation. Issues of translation and cross-cultural communication have been featured in three contemporary Asian productions that are themselves translations and adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays. To facilitate discussion, we will now turn to three adaptations of King Lear that present the play in monolingual, bilingual, and multilingual formats. These works share the same conviction to link Lear to contemporary Asian cultures and political history. At the same time, they are set apart from one another by their distinctive approaches to the problem of self-identity in Lear and in contemporary culture. Lear is chosen as our case study because it occupies a special place in the history of Asian theatre since some scenes were first performed in English in Chowringhee Theatre, Calcutta, in 1832, and because the three adaptations provide usefully contrasting perspectives on intersemiotic translation. Videos of these three productions are also freely accessible on the Asian portal of the Global Shakespeares digital archive (http://web.mit.edu/shakespeare/asia/). Filial piety, patriarchal authority, and self-knowledge are among the themes that resonate with Asian directors and audiences’ concerns.

Taiwan-based director and actor Wu Hsing-kuo’s solo Beijing opera adaptation in Mandarin Chinese, titled Lear Is Here (2001), is a postmodern pastiche of ten characters including Wu himself as a character. The Buddhist interpretation of Lear also informed Wu’s autobiographical narratives. As a Beijing opera actor in Taiwan where recent nativist campaigns have generated an essentialist discourse about bona fide Taiwan identity, Wu found himself at the mercy of the island government and residents’ anti-Chinese sentiments. Adding insult to injury, Wu has been seen as a rebellion to the Beijing opera tradition because of his interest in intercultural theatre and Western drama. With his wife Lin Hsiu-wei, dancer and choreographer, he founded the Contemporary Legend Theatre in Taipei in 1986. Among the company’s best known Beijing opera plays are The Kingdom of Desire (Macbeth), The Revenge of the Prince (Hamlet), The Tempest, Oresteia, and Medea. The tension between father and child in Lear provided a framework for Wu to explore his uneasy relationship with his Beijing opera master and with the establishment in general. In more ways than one, the play has become a ritual that redeems Wu through public performance of a private experience. Wu’s adaptation opens with the scene of the mad Lear in the storm (3.2), a solo tour-de-force during which he combines modern dance steps, Beijing opera gestures, strides, minced steps, somersaults, and striking movement of his long Beijing opera beard and sleeves to “translate” Lear’s interrogation of the heaven.

Toward the end of this scene, he asks “Who am I?” first as Lear and then as himself, an actor (fig. 5 and 6). The question is fundamental in Lear, and the first act of Lear Is Here retains a line-by-line translation of the following passage:

Lear: Doth any here know me? This is not Lear.

Doth Lear walk thus? Speak thus? Where are his eyes?

Either his notion weakens, his discernings

Are lethargied—Ha! Waking? ‘tis not so.

Who is it that an tell me who I am? (1.4.226-30)

Wu brings his life experience to bear on Lear, and eventually transforms himself out of the character on stage, a radical move in Beijing opera performance. He takes off his headdress and armour costume in full view of the audience, and uses the now eyeless headdress and beard as a fictional interlocutor. As well, Wu’s resistance to the rigid system of performance passed down by his master takes other forms such as cross-dressing. Trained in the male combatant role type, Wu specializes in characters that are generals, patriarchs, or ministers. Beijing opera actors do not usually cross over to other role types. In the solo performance, Wu not only plays the wronged father, but also the unruly daughters, a wronged son (Edgar), and the blinded Gloucester. Lear Is Here taps into a rich reservoir of nonverbal signs, via Beijing opera and experimental theatre, to translate some of the most powerful emotions in Shakespeare’s play.

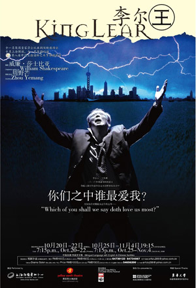

The theme of generational gap in King Lear also lends itself to experiments with languages. Chinese-British director David Tse staged a Mandarin-English bilingual version of King Lear in 2006 with his London based Yellow Earth Theatre in collaboration with Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre. The Buddhist notion of redemption and reincarnation informs some of the design elements and presentational styles. The production opens and closes with video footage, projected onto the three interlaced floor-to-ceiling reflective panels, that hints at both the beginning of a new life and life as endless suffering. Images of the faces of suffering men and women dissolve to show a crying newborn being held upside down and smacked. The production toured China and the UK and was staged during the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Complete Works Festival. Set in 2020 against the backdrop of cosmopolitan Shanghai, this futuristic adaptation reframed the epistemological gap between Lear and Cordelia in terms of linguistic difference. The play is close to Tse’s heart, as he believes that Lear speaks strongly to diaspora artists and audiences who maintain links, but are unable to fully communicate, with their families residing in their home countries. As the poster (fig. 7) makes abundantly clear, the production focuses on the questions of heritage and filial piety. The tag line, in Mandarin and English, reads “Which of you shall we say doth love us most?” Each of the characters has a primary language: English or Mandarin. On rare occasions, the characters may switch between two languages. Bilingual supertitles are provided. Lear’s famous test of love in the division-of-the-kingdom scene is framed within the context of Confucianism. The Confucian family values implicate family roles into the social hierarchy, and the Shanghai Lear insists on respect from his children at home and in business settings. Lear, a business tycoon, solicits confessions of love from  his three daughters. Residing in Shanghai, Regan and Goneril are fluent in Chinese and are ever so articulate as they convince their father of their unconditional love of him. Cordelia, on the other hand, is both honest and linguistically challenged. She is unwilling to follow her sisters’ example, but she is unable to communicate in Chinese with her father, either. Her silence, therefore, takes on new meanings. A member of the Chinese diaspora in London, Cordelia participates in this important family and business meeting via video link. Ironically but perhaps fittingly, the only Chinese word at her disposal is meiyou (“nothing”). In the tense exchange between Cordelia and Lear, the word nothing looms large as Chinese fonts are projected onto the screen panels behind which Cordelia stands. Uninterested in the ontological or lexical significance of nothing, Lear urged Cordelia to give him something. The production capitalises on the presence of two cultures and the gap between them, and the bilingualism on stage is supplemented by bilingual supertitles. Whether in the UK or China, the majority of its audiences could only follow one part of the dialogue at ease and had to switch between the action on stage and the supertitles. The play thus embodies the realities of globalisation through translation as a metaphor and a plot device.

his three daughters. Residing in Shanghai, Regan and Goneril are fluent in Chinese and are ever so articulate as they convince their father of their unconditional love of him. Cordelia, on the other hand, is both honest and linguistically challenged. She is unwilling to follow her sisters’ example, but she is unable to communicate in Chinese with her father, either. Her silence, therefore, takes on new meanings. A member of the Chinese diaspora in London, Cordelia participates in this important family and business meeting via video link. Ironically but perhaps fittingly, the only Chinese word at her disposal is meiyou (“nothing”). In the tense exchange between Cordelia and Lear, the word nothing looms large as Chinese fonts are projected onto the screen panels behind which Cordelia stands. Uninterested in the ontological or lexical significance of nothing, Lear urged Cordelia to give him something. The production capitalises on the presence of two cultures and the gap between them, and the bilingualism on stage is supplemented by bilingual supertitles. Whether in the UK or China, the majority of its audiences could only follow one part of the dialogue at ease and had to switch between the action on stage and the supertitles. The play thus embodies the realities of globalisation through translation as a metaphor and a plot device.

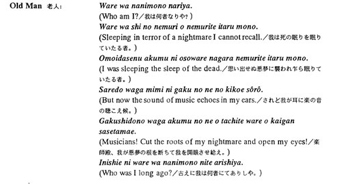

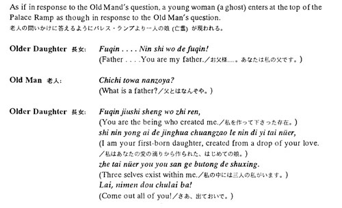

While Tse’s and Wu’s Lears have borne personal significance for their creators to varying extents, Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s pan-Asian multilingual production of Lear (1997a) brings national and regional identities to the fore. Akin to visual poetry, the production featured actors from several different Asian countries, performing in different Asian languages and performance styles representing their countries of origin. Wu superimposes autobiographical traces onto Lear. Tse sees the question of self identity as one without fixed answers in an age of linguistic globalisation. Ong brings the amalgamated performance styles from noh, pencak silat, Beijing opera, and other traditional theatres to personify a “new Asia” that is having an ongoing dialogue with “the old, with traditions, with history” (1997b, 5). He stresses that a harmonious world unified by superimposed ideologies is not what he seeks, for “we can no longer hold onto simple visions of the outside world and the ‘other’” (5). The Old Man, the Lear figure, walks the stage in the solemn style of noh theatre and speaks Japanese, while the Older Daughter (embodying the shadows of Goneril and Regan) is performed cross-dressed in the style of Beijing opera in Mandarin. The younger sister (Cordelia) speaks Thai, though she remains silent most of the time. The Older Daughter has this to say about the Cordelia figure: “She is always silent. Nobody knows what she is scheming in her mind” (Ong, 1997a). The assassins sent by the Older Daughter speak Indonesian. The confrontation between the Japanese-speaking patriarch and Mandarin-speaking daughter brings to mind the Sino-Japanese conflicts throughout the twentieth century. As with Tse’s version, the father-child relation is significant in Ong’s rendition. The production opens with the Old Man and the Elder Daughter engaged in a philosophical conversation (fig. 8), followed by a ritualised division-of-the-kingdom scene.

The Old Man’s questions, “who am I?” and “what is a father?,” as it turns out, are far from rhetorical ones, and the Older Daughter’s initial answer is insufficient. The Older Daughter defines the patriarchal role as one that exerts power, and aspires to such a position and does not refrain from making these desires known throughout the play. At the end of the play, she stabs the Old Man and declares herself “a powerful puppeteer.” She soon realizes, however, that “killing you, I become myself”; she becomes the patriarchal figure she wishes to eliminate, and now she has to live with it. The play concludes with great silence and a sense of solitude.

At the core of all three productions lie the question: “Who am I?” At stake are the artists personal and cultural identities as the processes of globalisation intensify. The question is as urgent for Lear as it is for contemporary translators, directors, and audiences.

Conclusion

How many ages hence

Shall this our lofty scene be acted over,

In states unborn and accents yet unknown!

—Julius Caesar 3.1.112-114

Cassius’ remarks in the scene of Julius Caesar’s assassination are not without prophetic insight. Shakespeare transformed a great number of sources that enriched his works, and his plays have been translated into a wide range of languages and genres. It is useful to think of translation as a love affair involving two equal partners, because it allows us an unimpaired view of the event, and eschews such hierarchical constructs as a superior original and a necessarily lesser derivative. The production and reception of translated works—either literal translation of words into another language (e.g., the Hebrew Bible to the Geneva Bible) or the transformation of meanings into a new form of expression (stage play to film noir)—imply double perspectives and have a significance that goes beyond the simple transfer of semantic meanings. A translator is an interpreter of the literary text and its cultural contexts, and a reader of the translation is no less a mediator between many possible worlds and meanings. Contradictory to the purists’ anxiety that the proliferation of Shakespeare in translation, whether in modern English or foreign languages, will spell the demise of Shakespeare’s oeuvre, the rise of a global industry of translation speaks to the power of Shakespeare’s words—not bound within the limit of one language and historical period but open to a wide spectrum of interpretive possibilities, a common feature shared by great works of art.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter (2004). “The task of the translator.” Trans. Harry Zohn. In Lawrence Venuti (Ed). The Translation Studies Reader, 2nd Ed. (pp. 75-86). New York: Routledge.

Burnett, Mark Thornton (2005). “Writing Shakespeare in the global economy.” Shakespeare Survey 58: 185-198.

Cross, Francis W. (1898). History of the Walloon and Huguenot Church at Canterbury. London: Publications of the Huguenot Society of London.

Derrida, Jacques (1985). “Roundtable on translation.” Trans. Peggy Kamuf. In Christie V. McDonald (Ed). The Ear of the Other: Otobiography, Transference, Translation (pp. 91-161) New York: Schocken Books.

Eco, Umberto (2001). Experiences in Translation. Trans. Alastair McEwen. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Feng, Xiaogang, dir. (2006). Ye yan (The Banquet). Hong Kong: Huayi Brothers and Media Asia.

Hansen, Niels B. (2008). “‘Something is Rotten …’.” In Ros King and Paul J. C. M. Franssen (Eds). Shakespeare and War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hoenselaars, Ton (2004). “Introduction: Shakespeare’s history plays in Britain and abroad.” In Ton Hoenselaars (Ed). Shakespeare’s History Plays: Performance, Translation and Adaptation in Britain and Abroad. (pp. 9-34). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— (2009). “Translation futures: Shakespearians and the foreign text.” Shakespeare Survey 62: 273-282.

Jakobson, Roman (2004). “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” In Lawrence Venuti (Ed). The Translation Studies Reader, 2nd Ed. (pp. 138-143). New York: Routledge.

Kyd, Thomas (2005). The Spanish Tragedy, in Renaissance Drama: An Anthology of Plays and Entertainments, 2nd Ed. Ed. Arthur F. Kinney. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 143-191.

Lamb, Charles and Mary (1963), Tales from Shakespeare. London: Dent.

Levin, Carole and John Watkins (2009). Shakespeare’s Foreign Worlds: National and Transnational Identities in the Elizabethan Age. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Morse, Ruth (2006). “Reflections in Shakespeare translation.” The Yearbook of English Studies 36.1: 79-89.

Ong, Keng Sen, dir. (1997a). Lear. TheatreWorks, Singapore. Video and documentary with subtitles freely accessible on /

—. (1997b). “Lear: Linking Night and Day.” In Lear (stage bill). (p. 5). Tokyo: The Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Parker, Patricia (2001). “The novelty of different tongues: Polyglot punning in Shakespeare (and others).” In François Laroque and Franck Lessay (Eds). Esthétiques de la Nouveauté à la Renaissance. (pp. 41-58). Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle.

Pestana, Alice (1930). “The king of Portugal’s translation of Hamlet (1877).” In Alice Pestana, Alice Pestana 1860-1929: In Memoriam. (pp. 248-263). Madrid: Julio Cosano.

Pfister, Manfred, and Jürgen Gutsch, ed. (2009). William Shakespeare’s Sonnets for the First Time Globally Reprinted: A Quartercentenary Anthology with a DVD. Dozwill, Switzerland: Edition Signathur.

Quinn, Aragorn (2011). “Political theatre: two translations of Julius Caesar in Meiji Japan.” In Alexa Huang (Ed). “Shakespeare and Asia,” a special issue of Asian Theatre Journal 28. 1 (Spring): forthcoming.

Ricoeur, Paul (2006). On Translation. Trans. Eileen Brennan. London: Routledge.

Rothwell, Kenneth S. (2004). A History of Shakespeare on Screen: A Century of Film and Television, 2nd Ed. Cambridge

Shakespeare, William (2005). The Norton Shakespeare, 2nd Ed. Stephen Greenblatt (Ed). New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Tse, David, dir. (2006). King Lear. Yellow Earth Theatre (London) and Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre. Video with subtitles freely accessible on /

Wu, Hsing-kuo, dir. and perf. (2001). Li’er zaici (Lear Is Here). The Contemporary Legend Theatre, Taipei. Video with subtitles freely accessible on /